Cadaver monument

A cadaver monument or transi (or memento mori monument, Latin for "reminder of death") is a type of church monument to deceased persons featuring a sculpted effigy of a skeleton or an emaciated, even decomposing, dead body. It was particularly characteristic of the later Middle Ages[1] and was designed to remind the passer-by of the transience and vanity of mortal life and the eternity and desirability of the Christian after-life. The person so represented is not necessarily entombed or buried exactly under the monument, nor even in the same church.[2]

Overview

A depiction of a rotting cadaver in art (as opposed to a skeleton) is called a transi. However, the term "cadaver monument" can really be applied to other varieties of monuments, e.g. with skeletons or with the deceased completely wrapped in a shroud. In the "double-decker" monuments, in Erwin Panofsky's phrase,[4] a sculpted stone bier displays on the top level the recumbent effigy (or gisant) of a living person, where they may be life-sized and sometimes represented kneeling in prayer, and in dramatic contrast as a rotting cadaver on the bottom level, often shrouded and sometimes in company of worms and other flesh-eating wildlife. The iconography is regionally distinct: the depiction of such animals on these cadavers is more commonly found on the European mainland, and especially in the German regions.[5] The dissemination of cadaver imagery in the late-medieval Danse Macabre may also have influenced the iconography of cadaver monuments.[6]

In Christian funerary art, cadaver monuments were a dramatic departure from the usual practice of depicting the deceased as they were in life, for example recumbent but with hands together in prayer, or even as dynamic military figures drawing their swords, such as the 13th- and 14th-century effigies surviving in the Temple Church, London.

The term can also be used for a monument which shows only the cadaver without a corresponding representation of the living person. The sculpture is intended as a didactic example of how transient earthly glory is, since it depicts what all people of every status finally become. Kathleen Cohen's study of five French ecclesiastics who commissioned transi monuments determined that common to all of them was a successful worldliness that seemed almost to demand a shocking display of transient mortality. A classic example is the "Transi de René de Chalons" by Ligier Richier, in the church of Saint Etienne in Bar-le-Duc, France.[7]

These cadaver monuments, with their demanding sculptural devices, were made only for high-ranking persons, usually royalty, bishops, abbots or nobility, because one had to be wealthy to have one made, and influential enough to be allotted space for one in a church of limited capacity. Some monuments for royalty were double tombs, for both a king and queen. The French kings Louis XII, Francis I and Henry II were doubly portrayed, as couples both as living effigies and as naked cadavers, in their double double-decker monuments in the Basilica of Saint-Denis near Paris. Other varieties also exist, such as cadaver imagery on incised slabs and monumental brasses, including the so-called "shroud brasses", of which many survive in England.[8]

Countries

England

The earliest known transi monument is the very faint matrix (i.e. indent) of a now lost monumental brass shrouded demi-effigy on the ledger stone slab commemorating "John the Smith" (c.1370) at Brightwell Baldwin in Oxfordshire.[9] In the 15th century the sculpted transi effigy made its appearance in England.[10] Cadaver monuments survive in many English cathedrals and parish churches. The earliest surviving one is in Lincoln Cathedral, to Bishop Richard Fleming who founded Lincoln College, Oxford and died in 1431. Canterbury Cathedral houses the well-known cadaver monument to Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury (died 1443) and in Exeter Cathedral survives the 16th-century monument and chantry chapel of Precentor Sylke, inscribed in Latin: 'I am what you will be, and I was what you are. Pray for me I beseech you'. Winchester Cathedral has two cadaver monuments.

The cadaver monument traditionally identified as that of John Wakeman, Abbot of Tewkesbury from 1531 to 1539, survives in Tewkesbury Abbey. Following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, he retired and later became the first Bishop of Gloucester. The monument, with vermin crawling on a sculpted skeletal corpse, may have prepared for him, but his body was in fact buried at Forthampton in Gloucestershire.

A rarer post-medieval example is the standing shrouded effigy of the poet John Donne (d. 1631) in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral in London.[11] Similar examples from the Early Modern period signify faith in the Resurrection.[12]

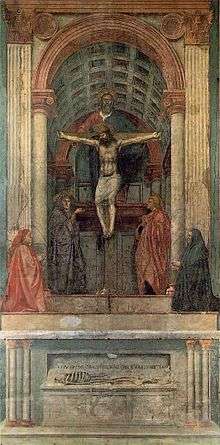

Italy

Cadaver monuments are found in many Italian churches. Andrea Bregno sculpted several of them, including those of Cardinal Alain de Coëtivy in Santa Prassede, Ludovico Cardinal d'Albert at Santa Maria in Aracoeli and Bishop Juan Díaz de Coca in Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.[13]

Three other prominent monuments are those of Cardinal Matteo d'Acquasparta in Santa Maria in Aracoeli;[14] those of Bishop Gonsalvi (1298) and of Cardinal Gonsalvo (1299) in Santa Maria Maggiore, all sculpted by Giovanni de Cosma,[13] the youngest of the Cosmati family lineage.

Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome contains yet another monument, the tomb of Pope Innocent III,[14] sculpted by Giovanni Pisano.[13]

France

.jpg)

France has a long history of cadaver monuments, though not as many examples or varieties survive as in England. One of the earliest and anatomically convincing examples is the gaunt cadaver effigy of the medieval physician Guillaume de Harsigny (d. 1393) at Laon.[15] Another early example is the effigy on the multi-layered wall-monument of Cardinal Jean de La Grange (died 1402) in Avignon. Kathleen Cohen lists many further extant examples. A revival of the form occurred in the Renaissance, as testified by the two examples to Louis XII and his wife Anne of Brittany at Saint-Denis, and of Queen Catherine de Medici who commissioned a cadaver monument for her husband Henry II.

Germany and the Netherlands

Many cadaver monuments and ledger stones survive in Germany and the Netherlands. An impressive example is the sixteenth-century Van Brederode double-decker monument at Vianen near Utrecht, which depicts Reynoud van Brederode (d. 1556) and his wife Philippote van der Marck (d. 1537) as shrouded figures on the upper level, with a single verminous cadaver below.

Ireland

A total of 11 cadaver monuments have been recorded in Ireland, many of which are no longer in situ. The earliest complete record of these monuments was compiled by Helen M. Roe in 1969.[16] One of the best known examples of this tradition is the monumental limestone slab known as 'The Modest Man', dedicated to Thomas Ronan (d. 1554), and his wife Johanna Tyrry (d. 1569), now situated in the Triskel Christchurch in Cork. This is one of two examples recorded in Cork, with the second residing in St. Multose Church in Kinsale.

A variant is in the form of Cadaver Stones, which lack any sculpted superstructure or canopy. These may merely be sculptural elements removed from more elaborate now lost monuments, as is the case with the stone of Sir Edmond Goldyng and his wife Elizabeth Fleming, which in the early part of the 16th century was built into the churchyard wall of St. Peter's Church of Ireland, Drogheda.

References

- Cohen, Kathleen (1973). Metamorphosis of a Death Symbol: The Transi Tomb in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Location of burial (i.e. "tomb") determined by prestige, i.e. "before the high altar", "on the north side of the chancel" (traditional founder's location) or merely by availability of space limited by physical features of the foundations of the building, or by location of crypt if relevant. Location of corresponding above ground monument determined by similar factors.

- Oosterwijk, Sophie (2005). "Food for worms – food for thought. The appearance and interpretation of the 'verminous' cadaver in Britain and Europe". Church Monuments. 20: 63, 133–40.

- Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture (New York) 1964:65.

- Oosterwijk, Sophie (2005). "Food for worms – food for thought. The appearance and interpretation of the 'verminous' cadaver in Britain and Europe". Church Monuments. 20: 40–80, 133–40.

- Oosterwijk, Sophie (2008). "'For no man mai fro dethes stroke fle'. Death and Danse Macabre iconography in memorial art". Church Monuments. 23: 62–87, 166–68.

- Janvier, François (2004). "Restauration du 'Squelette' de Ligier Richier à Bar-le-Duc". Le Journal du Conservateur. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-04-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Brightwell Baldwin slab is discussed by Sally Badham in her essay "Monumental brasses and the Black Death - a reappraisal', Antiquaries Journal, 80 (2000), 225-226.

- Pamela King examines the phenomenon of English cadaver tombs in her essay "The cadaver tomb in the late fifteenth century: some indications of a Lancastrian connection", in Dies Illa: Death in the Middle Ages: Proceedings of the 1983 Manchester Colloquium, Jane H.M. Taylor, ed.

- http://churchmonumentssociety.org/Monument%20of%20the%20Month%20Archive/2010_11.html

- Jean Wilson, "Go for Baroque: The Bruce Mausoleum at Maulden, Bedfordshire", Church Monuments, 22 (2007), 66-95.

- Scott, Leader (1882). Ghiberti and Donatello with Other Early Italian Sculptors. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. pp. 27–50.

- "Guide to Rome." Online at: http://www.romecity.it/Berninieglialtri.htm.

- http://www.churchmonumentssociety.org/Monument%20of%20the%20Month%20Archive/2010_10.html

- Roe, Helen M. (1969). "Cadaver Effigial Monuments in Ireland". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 99: 1–19. JSTOR 25509699.