Bromide (language)

Bromide in literary usage means a phrase, cliché, or platitude that is trite or unoriginal. It can be intended to soothe or placate; it can suggest insincerity or a lack of originality in the speaker.[1][2] Bromide can also mean a commonplace or tiresome person, a bore (a person who speaks in bromides).

| Look up bromide in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Etymology

Literal meanings

Bromide has both literal and figurative meanings. The word originally derives from chemistry in which it can be used to describe a compound containing the element bromine, especially as a salt or bonded to an alkyl radical. Bromine was isolated independently by two chemists, Carl Jacob Löwig (in 1825) and Antoine Jérôme Balard (in 1826) and the first appearance in print of "bromide" as a chemical term has been attributed to 1836.[2][3]

By the 1870s silver halides, such as silver bromide, were in commercial use as a photographic medium. Over time, especially in British Commonwealth countries, the word "bromide" came to mean a photographic print;[2][4] exactly when this occurred is not clear. As digital photography replaced chemical-based photography at the end of the 20th century, this usage has declined.

Bromine salts were discovered by the mid 19th century to have calming effects on the central nervous system. In 1857 it was first reported in a medical journal that potassium bromide could be used as an anti-epileptic drug.[5] This action derived from the sedative effects that were calming and tranquilizing but not sleep inducing. Its medicinal use grew so widespread in the latter half of that century that single hospitals might use as much as several tons in a year (the dose being a few grams per day per person).[6] American physician Silas Weir Mitchell, considered to be the father of neurology, also reported lithium bromide to be an anticonvulsant and hypnotic in 1870; and later advocated use of all the bromides to calm "general nervousness."[7] Sodium bromide had a narrower range of safety and efficacy but it was an ingredient in remedies such as Bromo-Seltzer that were popular for headaches and hangovers, in part due to the sedative effects.[8]

Figurative meanings

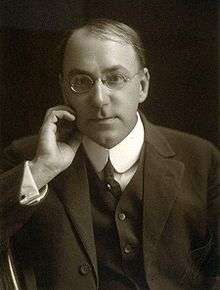

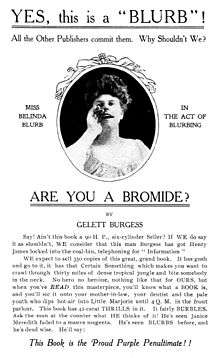

By the turn of the 20th century, "bromide" was widely understood in the context of a being a sedative or being sedate. It was then, in April 1906, that American humorist Gelett Burgess (1866-1951) published an essay in The Smart Set, a magazine edited by George Jean Nathan and H. L. Mencken, called "The Sulphitic Theory". It was here where Burgess is credited for coining the usage of bromide as a personification of a sedate, dull person who said boring things.[9][10] In the fall of 1906, he published a revised and enlarged essay in the form of a small book, Are You a Bromide?[11] (Burgess is also credited for coining the term "blurb" at this same time.[9] ) The book's full title was Are You a Bromide? Or, The Sulphitic Theory Expounded and Exemplified According to the Most Recent Researches Into the Psychology of Boredom: Including Many Well-known Bromidioms Now in Use. In these works he labeled a dull person as a "Bromide" contrasted with a "Sulphite" who was the opposite. Bromides meant either the boring person himself or the boring statement of that person, with Burgess providing many examples.

This usage persisted through the 20th century into the 21st century. Some well known quotes (or bromides) in current usage that appeared in Burgess' Are You a Bromide? include:

- "I don't know much about Art, but I know what I like."

- "... she doesn't look a day over fifty."

- "You'll feel differently about these things when you're married."

- "It isn't so much the heat... as the humidity...."

- "You're a sight for sore eyes."

See also

- Cliché

- Trope (literature)

- Idiom

- Open source e-book: "Are You a Bromide?" (California Digital Library)

- Related 1906 newspaper article: Gallagher, James (December 30, 1906). "Are You a Bromide? Or, Are You a Sulphite?". The San Francisco Call – via U.S. Library of Congress Chronicling America archive.

References

- "The Free Dictionary".

- "Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition". HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "A.Word.A.Day: bromide". Wordsmith.org. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "Meaning of the word "bromide" in "an additional charge for special presentations (e.g. bromides)"". English Language Learners Stack Exchange. Stack Overflow. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Pearce, J.M.S. (2002). "Bromide, the first effective antiepileptic agent". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 72 (3): 412. doi:10.1136/jnnp.72.3.412. PMC 1737805. PMID 11861713.

- Goodman, Alfred; Gilman, Louis S. (1970). "Chapter 10: Hypnotics and Sedatives". The Biological Basis of Therapeutics (4th ed.). London: MacMillan. pp. 121–2.

- Mitchell, Silas W. (1896). "On the Exceptional Effects of Bromides". Transactions of the Association of American Physicians. 11: 195–205.

- Lockhart; Schulz; Lindsey; Schriever; Serr (2014). "Bromo-Seltzer in the Cobalt Blue Bottles" (PDF). Society for Historical Archaeology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Metcalf, Alan A. (2004). Predicting New Words - The Secrets of Their Success. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 36–42. ISBN 0-618-13006-3. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Gertz, Stephen J. (17 August 2010). "The First Official (and Still Best) Publisher's "Blurb"". Booktryst. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Burgess, Gelett (October 1906). Are You A Bromide, Or The Sulphitic Theory. Internet Archive (archive.org): B.W. Huebsch. p. 74. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 27 August 2017.