Bombardment of Algiers (1683)

The bombardment of Algiers in 1683 was a French naval operation against the Regency of Algiers during the Franco-Algerian War of 1681-88. It led to the rescue of more than 100 French prisoners,[1] in some cases after decades of captivity, but the great majority of Christian slaves in Algiers were not liberated.

| Bombardment of Algiers, 1683 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Franco-Algerian War (1681-88) | |||||||||

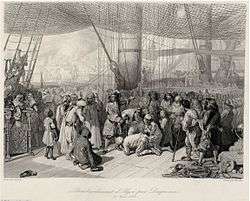

Augustin Burdet, Duquesne liberating the captives after the bombardment of Algiers in 1683, engraving after François-Auguste Biard. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Abraham Duquesne | Baba Hassan, Hadji-Hassein | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

17 ships of the line 3 frigates 16 galleys 7 bomb galiots 48 longboats 18 fluyts 8 tartans | unknown | ||||||||

Background

The previous year, Louis XIV had ordered Duquesne to bombard Algiers after the Dey declared war on France. At the head of a forty-strong fleet, Duquesne sailed to Algiers in July 1682, but bad weather delayed his attack. After several bombardments in August, the city suffered serious damage, but bad weather prevented the signing of a conclusive peace agreement, forcing Duquesne to return to France.

In the Spring of 1683, Duquesne set to sea once again with a fleet of 17 ships of the line, 3 frigates, 16 galleys, 7 bomb galiots, 48 longboats, 18 fluyts and 8 tartanes. This was a larger force than had been sent to Algiers the previous year. As well as being more numerous, the galiots were better equipped and manned by a special corps of bombardiers.[2] The fleet set sail from Toulon on 23 May.

Second bombardment of Algiers

The bombardment began on the night of 26-27 June, and two hundred and twenty two bombs, launched in less than twenty four hours, started fires in Algiers and prompted general disorder as well as killing around 300 Algerians. Hassan Dey intended to resist nonetheless, but the population urged him to sue for peace. Duquesne agreed to a truce on condition that all Christian slaves were delivered to him. When the truce expired, Hassan Dey asked for, and received, an extension. Duquesne meanwhile set out his terms for agreeing a peace:

- freeing all Christian slaves

- an indemnity equal to the value of all the goods seized from France by pirates

- a solemn embassy to be sent to Louis XIV to ask his forgiveness for the hostile acts committed against his navy.

These terms resolved the Dey to continue resistance.[2]

One of the Algerian commanders, Mezzo Morto Hüseyin Pasha, then seized command and denounced the cowardice of the Dey, who had agreed to treat with the French. He had him put to death and was acclaimed as his successor by the janissaries. Before long a red flag, raised from the heights of the Casbah, announced to Duquesne that combat was resumed.[2] The Algerians replied to the bombs hurled at their city by tying the French consul, Jean Le Vacher to the mouth of a cannon.[3] On 28 July pieces of his shattered limbs fell on the decks of the French vessels, along with those of other French prisoners blown to pieces.[1]

Despite the fierce resistance of the Algerians, the city was engulfed by an enormous fire which consumed palaces, mosques, and many other buildings across the city; the wounded could not find any refuge; and ammunition ran low. Algiers would have been reduced to ruins had not Duquesne himself run out of missiles. The bombardment ended on 29 July.

The pride of the Algerian pirates was crushed, and as the French fleet returned to France, Algiers sent an embassy under Djiafar-Aga-Effendi to ask forgiveness of Louis XIV, for the injuries and cruelty that the corsairs had inflicted on France.[4][2]

Aftermath

The new Dey Mezzo Morto Hüseyin Pasha agreed to free another 546 captives,[5][3] but refused to sign a peace agreement with Duquesne, who was then 79 years of age, so Louis XIV sent another envoy, Tourville, to treat with him. A hundred year peace was agreed, including a provision to leave the coasts of France unmolested. Five years later, after Algiers violated the treaty, the French again bombarded the city. Admiral d'Estrées obliged the Dey to seek a new peace agreement, signed on 27 September 1688, which the Algerians respected. Thereafter the corsair captains, though they avoided the coasts of France, continued their raids elsewhere, causing considerable damage to the coastal regions of Spain.[6]

References

- Clement Melchior Justin Maxime Fourcheux de Montrond (1860). Les marins les plus celebres. Par ---. 5. ed. Lefort. p. 55.

- Michelant, L. "Bombardement d'Alger par Duquesne". Faits mémorables de l'histoire de France. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Daniel Panzac (2005). The Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800-1820. BRILL. p. 33. ISBN 90-04-12594-9.

- Alan G. Jamieson (15 February 2013). Lords of the Sea: A History of the Barbary Corsairs. Reaktion Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-86189-946-0.

- Paul Eudel (1902). L'orf?vrerie alg?rienne et tunisienne. Рипол Классик. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-5-87318-342-5.

- France. Ministère de la marine et des colonies, Revue maritime et coloniale / Ministère de la marine et des colonies, Librairie de L. Hachette (Paris), 1861-1896, page 663

Bibliography

- Vergé-Franceschi, Michel (2002). Dictionnaire d'Histoire maritime. Bouquins (in French). Paris: éditions Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-08751-8.

- Meyer, Jean; Acerra, Martine (1994). Histoire de la marine française (in French). Rennes: éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 2-7373-1129-2.

- Monaque, Rémi (2016). Une histoire de la marine de guerre française (in French). Paris: éditions Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-03715-4.

- Taillemite, Étienne (2002). Dictionnaire des marins français (in French). Paris: éditions Tallandier. ISBN 2-84734-008-4.

- Bély, Lucien (2015). Dictionnaire Louis XIV. Bouquins (in French). éditions Robert Laffont. ISBN 978-2-221-12482-6.

- Le Moing, Guy (2011). Les 600 plus grandes batailles navales de l'Histoire. Marines Éditions. ISBN 978-2-35743-077-8.

- Courtinat, Roland (2003). La piraterie barbaresque en Méditerranée: XVIe – XIXe siècle (in French). Serre Éditeur. p. 61.

- Peter, Jean (1997). Les barbaresques sous Louis XIV: le duel entre Alger et la Marine du Roi (1681-1698) (in French). Institut de stratégie comparée.

- John A. Lynn (2014). Les Guerres de Louis XIV. Tempus. éditions Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-04755-9.

- Henry Laurens, John Tolan, Gilles Veinstein, L’Europe et l’islam : quinze siècles d’histoire, Éditions Odile Jacob, 2009

- Sue, Eugène (1836). Histoire de la marine française: XVIIe siècle - Jean Bart (in French). F. Bonnaire. p. 121-151.

- Pellissier de Reynaud (1844). Mémoires historiques et géographiques sur l'Algérie (in French). Paris: Imprimerie royale. p. 274 et suiv.

- Troude, Onésime (1867–1868). Batailles navales de la France (in French). Paris: Challamel aîné.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Charles Bourel de La Roncière, Le Bombardement d'Alger en 1683, d'après une relation inédite, Imprimerie nationale, 1916, 55 pages (lire en ligne)

- La Roncière, Charles (1920). Histoire de la Marine française: La Guerre de Trente Ans, Colbert (in French). Paris: Plon.