Blackstone's ratio

In criminal law, Blackstone's ratio (also known as the Blackstone ratio or Blackstone's formulation) is the idea that:

It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.[1]

as expressed by the English jurist William Blackstone in his seminal work Commentaries on the Laws of England, published in the 1760s.

The idea subsequently became a staple of legal thinking in Anglo-Saxon jurisdictions and continues to be a topic of debate. There is also a long pre-history of similar sentiments going back centuries in a variety of legal traditions. The message that government and the courts must err on the side of bringing in verdicts of innocence has remained constant.

In Blackstone's Commentaries

The phrase, repeated widely and usually in isolation, comes from a longer passage, the fourth in a series of five discussions of policy by Blackstone:

Fourthly, all presumptive evidence of felony should be admitted cautiously, for the law holds that it is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer. And Sir Matthew Hale in particular lays down two rules most prudent and necessary to be observed: 1. Never to convict a man for stealing the goods of a person unknown, merely because he will give no account how he came by them, unless an actual felony be proved of such goods; and, 2. Never to convict any person of murder or manslaughter till at least the body be found dead; on account of two instances he mentions where persons were executed for the murder of others who were then alive but missing.

The phrase was absorbed by the British legal system, becoming a maxim by the early 19th century.[2] It was also absorbed into American common law, cited repeatedly by that country's Founding Fathers, later becoming a standard drilled into law students all the way into the 21st century.[3]

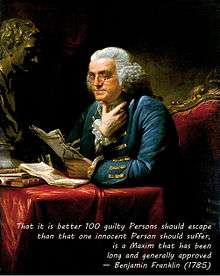

Other commentators have echoed the principle. Benjamin Franklin stated it as: "it is better 100 guilty Persons should escape than that one innocent Person should suffer".[4]

Defending British soldiers charged with murder for their role in the Boston Massacre, John Adams also expanded upon the rationale behind Blackstone's Ratio when he stated:

It is of more importance to the community that innocence should be protected, than it is, that guilt should be punished; for guilt and crimes are so frequent in this world, that all of them cannot be punished....when innocence itself, is brought to the bar and condemned, especially to die, the subject will exclaim, 'it is immaterial to me whether I behave well or ill, for virtue itself is no security.' And if such a sentiment as this were to take hold in the mind of the subject that would be the end of all security whatsoever

Given that Sir Matthew Hale and Sir John Fortescue in English law had made similar statements previously, some kind of explanation is required for the enormous popularity and influence of the phrase across all the Anglo-Saxon legal systems. Cullerne Bown has argued that it "...can be seen as a new kind of buttress of the law that was required in a new kind of society."[5][6]

Historic expressions of the principle

The immediate precursors of Blackstone's ratio in English law were articulations by Hale (about 100 years earlier) and Fortescue (about 200 years before that), both influential jurists in their time. Hale wrote: "for it is better five guilty persons should escape unpunished, than one innocent person should die." Fortescue's De Laudibus Legum Angliae (c. 1470) states that "one would much rather that twenty guilty persons should escape the punishment of death, than that one innocent person should be condemned and suffer capitally."[7]

Some 300 years before Fortescue, the Jewish legal theorist Maimonides wrote that "the Exalted One has shut this door" against the use of presumptive evidence, for "it is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death."[7][8][9]

Maimonides argued that executing an accused criminal on anything less than absolute certainty would progressively lead to convictions merely "according to the judge's caprice" and was expounding on both Exodus 23:7 ("the innocent and righteous slay thou not") and an Islamic text, [Jami'] of at-Tirmidhi.

[Jami'] of at-Tirmidhi quotes Muhammad as saying, "Avoid legal punishments as far as possible, and if there are any doubts in the case then use them, for it is better for a judge to err towards leniency than towards punishment". Another similar expression reads, "Invoke doubtfulness in evidence during prosecution to avoid legal punishments".[10]

Other statements, some even older, which seem to express similar sentiments have been compiled by Volokh. A vaguely similar principle, echoing the number ten and the idea that it would be preferable that many guilty people escape consequences than a few innocents suffer them, appears as early as the narrative of the Cities of the Plain in Genesis (at 18:23–32),[7]

Abraham drew near, and said, "Will you consume the righteous with the wicked? What if there are fifty righteous within the city? Will you consume and not spare the place for the fifty righteous who are in it?[11] ... What if ten are found there?" He [The Lord] said, "I will not destroy it for the ten's sake."[12]

With respect to the destruction of Sodom, the text describes it as ultimately being destroyed, but only after the rescuing of most of Lot's family, the aforementioned "righteous" among a city or overwhelming wickedness who, despite the overwhelming guilt of their fellows, were sufficient by their mere presence to warrant a "stay of execution" of sorts for the entire region, slated to be destroyed for being uniformly a place of sin. The text continues,

27 Early the next morning Abraham got up and returned to the place where he had stood before the Lord. 28 He looked down toward Sodom and Gomorrah, toward all the land of the plain, and he saw dense smoke rising from the land, like smoke from a furnace.[13]

29 So when God destroyed the cities of the plain, he remembered Abraham, and he brought Lot out of the catastrophe that overthrew the cities where Lot had lived.[14]

Similarly, on 3 October 1692, while decrying the Salem witch trials, Increase Mather adapted Fortescue's statement and wrote, "It were better that Ten Suspected Witches should escape, than that one Innocent Person should be Condemned."[15]

In current scholarship

Particularly in the United States, Blackstone's ratio continues to be an active source of debate in jurisprudence. For example Daniel Epps and Laura Appleman exchanged arguments against and in favour of its continuing influence in the Harvard Law Review in 2015.[16][17]

Viewpoints in politics

Authoritarian personalities tend to take the opposite view; Bismarck is believed to have stated that "it is better that ten innocent men suffer than one guilty man escape".[7] Pol Pot made similar remarks.[18] Wolfgang Schäuble referenced this principle while saying that it is not applicable to the context of preventing terrorist attacks.[19] Former American Vice President Dick Cheney said that his support of American use of "enhanced interrogation techniques" against suspected terrorists was unchanged by the fact that 25% of CIA detainees subject to that treatment were later proven to be innocent, including one who died of hypothermia in CIA custody. "I'm more concerned with bad guys who got out and released than I am with a few that in fact were innocent." Asked whether the 25% margin was too high, Cheney responded, "I have no problem as long as we achieve our objective. ... I'd do it again in a minute."[20]

Liberal columnist Ezra Klein supported California's SB 967 "Affirmative Consent" law with the same reasoning as Cheney's supported "enhanced interrogation techniques". While claiming the law was "terrible" and could be used to punish people who did not commit rape, Klein states "its overreach is precisely its value" and "ugly problems don't always have pretty solutions".[21]

Alexander Volokh cites an apparent questioning of the principle, with the tale of a Chinese professor who responds, "Better for whom?"[7]

References

Citations

- "Commentaries on the laws of England". J.B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, 1893.

- Re Hobson, 1 Lew. C. C. 261, 168 Eng. Rep. 1034 (1831) (Holroyd, J.).

- G. Tim Aynesworth, An illogical truism, Austin Am.-Statesman, 18 April 1996, at A14. Specifically, it is "drilled into [first year law students'] head[s] over and over again." Hurley Green, Sr., Shifting Scenes, Chi. Independent Bull., 2 January 1997, at 4.

- 9 Benjamin Franklin, Works 293 (1970), Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Benjamin Vaughan (14 March 1785)

- Cullerne Bown, William (2018). "Killing Kaplanism: Flawed methodologies, the standard of proof and modernity". The International Journal of Evidence & Proof: 136571271879838. doi:10.1177/1365712718798387.

- ""Quantitative Jurisprudence" blog".

- Alexander Volokh, 1997

- Moses Maimonides, The Commandments, Neg. Comm. 290, at 269-271 (Charles B. Chavel trans., 1967).

- Goldstein, Warren (2006). Defending the human spirit: Jewish law's vision for a moral society. Feldheim Publishers. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-58330-732-8. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- Exegesis of Sunan at-Tirmidhi - the Book of Punishments, Abu 'Isa Muhammad ibn 'Isa at-Tirmidhi, 884 C.E.

- Genesis 18:23 , World English Bible (draft form)

- Genesis 18:32 , World English Bible (draft form)

- Genesis 19:27–28 , World English Bible (draft form)

- Genesis 19:29 , World English Bible (draft form)

- "Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits". 1693. p. 66.

- "The Consequences of Error in Criminal Justice".

- "A Tragedy of Errors: Blackstone, Procedural Asymmetry, and Criminal Justice".

- Locard, Henri. Pol Pot's Little Red Book: The Sayings of Angkar. Silkworm Books, 2004. pp. 209.

- "Schäuble: Zur Not auch gegen Unschuldige vorgehen". FAZ.

- "Dick Cheney Simply Does Not Care That the CIA Tortured Innocent People", New York Magazine. 14 December 2014.

- Klein, Ezra (13 October 2014). ""Yes Means Yes" is a terrible law, and I completely support it".

Sources

- Volokh, Alexander (November 1997). "n Guilty Men"". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 146 (1): 173. Retrieved 10 July 2015.