Bioprospecting

Bioprospecting is the process of discovery and commercialization of new products based on biological resources. These resources or compounds can be important for and useful in many fields, including pharmaceuticals, agriculture, bioremediation, and nanotechnology.[1] Between 1981-2010, one third of all small molecule new chemical entities approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were either natural products or compounds derived from natural products. Despite indigenous knowledge being intuitively helpful, bioprospecting has only recently begun to incorporate such knowledge in focusing screening efforts for bioactive compounds.[2]

Bioprospecting may involve biopiracy, the exploitative appropriation of indigenous forms of knowledge by commercial actors, and can include the patenting of already widely used natural resources, such as plant varieties, by commercial entities.[3]

Biopiracy

The term biopiracy was coined by Pat Mooney,[4] to describe a practice in which indigenous knowledge of nature, originating with indigenous peoples, is used by others for profit, without authorization or compensation to the indigenous people themselves.[5] For example, when bioprospectors draw on indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants which is later patented by medical companies without recognizing the fact that the knowledge is not new or invented by the patenter, this deprives the indigenous community of their potential rights to the commercial product derived from the technology that they themselves had developed.[6] Critics of this practice, such as Greenpeace,[7] claim these practices contribute to inequality between developing countries rich in biodiversity, and developed countries hosting biotech firms.[6]

In the 1990s many large pharmaceutical and drug discovery companies responded to charges of biopiracy by ceasing work on natural products, turning to combinatorial chemistry to develop novel compounds.[4]

Famous cases of Biopiracy

The Maya ICBG controversy

The Maya ICBG bioprospecting controversy took place in 1999–2000, when the International Cooperative Biodiversity Group led by ethnobiologist Brent Berlin was accused of being engaged in unethical forms of bioprospecting by several NGOs and indigenous organizations. The ICBG aimed to document the biodiversity of Chiapas, Mexico and the ethnobotanical knowledge of the indigenous Maya people – in order to ascertain whether there were possibilities of developing medical products based on any of the plants used by the indigenous groups.[8][9]

The Maya ICBG case was among the first to draw attention to the problems of distinguishing between benign forms of bioprospecting and unethical biopiracy, and to the difficulties of securing community participation and prior informed consent for would-be bioprospectors.[10]

The rosy periwinkle

The rosy periwinkle case dates from the 1950s. The rosy periwinkle, while native to Madagascar, had been widely introduced into other tropical countries around the world well before the discovery of vincristine. Different countries are reported as having acquired different beliefs about the medical properties of the plant.[11] This meant that researchers could obtain local knowledge from one country and plant samples from another. The use of the plant for diabetes was the original stimulus for research. Effectiveness in the treatment of both Hodgkin's Disease and leukemia were discovered instead.[12] The Hodgkin's lymphoma chemotherapeutic drug vinblastine is derivable from the rosy periwinkle.[13]

The neem tree

In 1994, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and W. R. Grace and Company received a European patent on methods of controlling fungal infections in plants using a composition that included extracts from the neem tree (Azadirachta indica), which grows throughout India and Nepal.[14][15][16] In 2000 the patent was successfully opposed by several groups from the EU and India including the EU Green Party, Vandana Shiva, and the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) on the basis that the fungicidal activity of neem extract had long been known in Indian traditional medicine.[16] WR Grace appealed and lost in 2005.[17]

The Enola bean

.jpg)

The Enola bean is a variety of Mexican yellow bean, so called after the wife of the man who patented it in 1999.[18] The allegedly distinguishing feature of the variety is seeds of a specific shade of yellow. The patent-holder subsequently sued a large number of importers of Mexican yellow beans with the following result: "...export sales immediately dropped over 90% among importers that had been selling these beans for years, causing economic damage to more than 22,000 farmers in northern Mexico who depended on sales of this bean."[19] A lawsuit was filed on behalf of the farmers, and on April 14, 2005 the US-PTO ruled in favor of the farmers. An appeal was heard on 16 January 2008, and the patent was revoked in May 2008. A later appeal to the court against the revocation was unsuccessful as of October 2, 2008.

Basmati rice

In 2000, the US corporation RiceTec (a subsidiary of RiceTec AG of Liechtenstein) attempted to patent certain hybrids of basmati rice and semidwarf long-grain rice.[20] The Indian government intervened and several claims of the patent were invalidated.

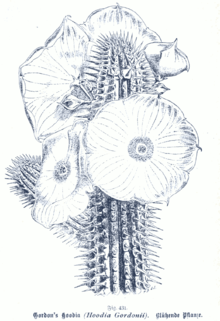

Hoodia

Hoodia, a succulent plant, originates from the Kalahari Desert of South Africa. For generations it has been known to the traditionally living San people as an appetite suppressant. In 1996 South Africa's Council for Scientific and Industrial Research began working with companies, including Unilever, to develop dietary supplements based on hoodia.[21][22][23][24] Originally the San people were not scheduled to receive any benefits from the commercialization of their traditional knowledge, but in 2003 the South African San Council made an agreement with CSIR in which they would receive from 6 to 8% of the revenue from the sale of Hoodia products.[25]

In 2008 after having invested €20 million in R&D on hoodia as a potential ingredient in dietary supplements for weight loss, Unilever terminated the project because their clinical studies did not show that hoodia was safe and effective enough to bring to market.[26]

Further cases

The following is a selection of further recent cases of biopiracy. Most of them do not relate to traditional medicines.

- Thirty six cases of biopiracy in Africa.[27]

- The case of the Maya people's pozol drink.[28][29]

- The case of the Maya and other people's use of Mimosa tenuifolia, including many other such cases in general are discussed at GRAIN

- The case of the Andean maca radish is discussed in the American University's Trade Environment Database

- The United Kingdom Select Committee on Environmental Audit 1999; Appendices to the Minutes of Evidence, Appendix 7: Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) and Farmers' Rights lists and describes the cases of turmeric (India),[30] karela (India), quinoa (Bolivia), brazzein berries (Gabon), and others.

- Captopril

Legal and political aspects

Patent law

One common misunderstanding is that pharmaceutical companies patent the plants they collect. While obtaining a patent on a naturally occurring organism as previously known or used is not possible, patents may be taken out on specific chemicals isolated or developed from plants. Often these patents are obtained with a stated and researched use of those chemicals. Generally the existence, structure and synthesis of those compounds is not a part of the indigenous medical knowledge that led researchers to analyze the plant in the first place. As a result, even if the indigenous medical knowledge is taken as prior art, that knowledge does not by itself make the active chemical compound "obvious," which is the standard applied under patent law.

In the United States, patent law can be used to protect "isolated and purified" compounds – even, in one instance, a new chemical element (see USP 3,156,523). In 1873, Louis Pasteur patented a "yeast" which was "free from disease" (patent #141072). Patents covering biological inventions have been treated similarly. In the 1980 case of Diamond v. Chakrabarty, the Supreme Court upheld a patent on a bacterium that had been genetically modified to consume petroleum, reasoning that U.S. law permits patents on "anything under the sun that is made by man." The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has observed that "a patent on a gene covers the isolated and purified gene but does not cover the gene as it occurs in nature".[31]

Also possible under US law is patenting a cultivar, a new variety of an existing organism. The patent on the enola bean (now revoked) was an example of this sort of patent. The intellectual property laws of the US also recognize plant breeders' rights under the Plant Variety Protection Act, 7 U.S.C. §§ 2321–2582.[32]

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

The CBD came into force in 1993. It secured rights to control access to genetic resources for the countries in which those resources are located. One objective of the CBD is to enable lesser-developed countries to better benefit from their resources and traditional knowledge. Under the rules of the CBD, bioprospectors are required to obtain informed consent to access such resources, and must share any benefits with the biodiversity-rich country.[33] However, some critics believe that the CBD has failed to establish appropriate regulations to prevent biopiracy.[34] Others claim that the main problem is the failure of national governments to pass appropriate laws implementing the provisions of the CBD.[35] The Nagoya Protocol to the CBD (negotiated in 2010, expected to come into force in 2014) will provide further regulations. The CBD has been ratified by all countries in the world except for Andorra, Holy See and United States. See also the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) and the 2001 International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture .

Bioprospecting contracts

The requirements for bioprospecting as set by CBD has created a new branch of international patent and trade law : bioprospecting contracts. Bioprospecting contracts lay down the rules, between researchers and countries, of benefit sharing and can bring royalties to lesser-developed countries. However, although these contracts are based on prior informed consent and compensation (unlike biopiracy), every owner or carrier of an indigenous knowledge and resources are not always consulted or compensated,[36] as it would be difficult to ensure every individual is included.[37] Because of this, some have proposed that the indigenous or other communities form a type of representative micro-government that would negotiate with researchers to form contracts in such a way that the community benefits from the arrangements.[37] Unethical bioprospecting contracts (as distinct from ethical ones) can be viewed as a new form of biopiracy.[34]

An example of a bioprospecting contract is the agreement between Merck and INBio of Costa Rica.[38]

Traditional knowledge database

Due to previous cases of biopiracy and to prevent further cases, the Government of India has converted traditional Indian medicinal information from ancient manuscripts and other resources into an electronic resource; this resulted in the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library in 2001.[39] The texts are being recorded from Tamil, Sanskrit, Urdu, Persian and Arabic; made available to patent offices in English, German, French, Japanese and Spanish. The aim is to protect India's heritage from being exploited by foreign companies.[40] Hundreds of yoga poses are also kept in the collection.[40] The library has also signed agreements with leading international patent offices such as European Patent Office (EPO), United Kingdom Trademark & Patent Office (UKTPO) and the United States Patent and Trademark Office to protect traditional knowledge from biopiracy as it allows patent examiners at International Patent Offices to access TKDL databases for patent search and examination purposes.[30][41][42]

See also

- Intellectual capital/Intellectual property

- Natural capital

- Biological patent

- Traditional knowledge/Indigenous knowledge

- Pharmacognosy

- Plant breeders' rights

- Bioethics

- Maya ICBG bioprospecting controversy

- International Cooperative Biodiversity Group

- Biological Diversity Act, 2002

References

- Beattie AJ, Hay M, Magnusson B, de Nys R, Smeathers J, Vincent JF (May 2011). "Ecology and bioprospecting". Austral Ecology. 36 (3): 341–356. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2010.02170.x. PMC 3380369. PMID 22737038.

- Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Savolainen V, Williamson EM, Forest F, Wagstaff SJ, Baral SR, Watson MF, Pendry CA, Hawkins JA (September 2012). "Phylogenies reveal predictive power of traditional medicine in bioprospecting". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (39): 15835–40. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10915835S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1202242109. PMC 3465383. PMID 22984175.

- Cluis C (2013). "Bioprospecting: A New Western Blockbuster, After the Gold Rush, the Gene Rush". The Science Creative Quarterly (8). The Science Creative Quarterly (University of British Columbia). Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Paterson R, Lima N (2016-12-12). Bioprospecting : success, potential and constraints. Paterson, Russell,, Lima, Nelson. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 9783319479354. OCLC 965904321.

- Park C, Allaby M. A dictionary of environment and conservation (3 ed.). [Oxford]. ISBN 9780191826320. OCLC 970401188.

- Wyatt T (2012). "Biopiracy". Encyclopedia of Transnational Crime & Justice. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 30. doi:10.4135/9781452218588.n11. ISBN 978-1-4129-9077-6.

- "Agriculture and Food". Green Peace Australia Pacific: What We Do: Food. Greenpeace. Archived from the original on 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Hayden C (2003). When Nature Goes Public: The Making and Unmaking of Bioprospecting in Mexico. Princeton University Press. pp. 100–105. ISBN 978-0-691-09556-1. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Feinholz-Klip D, Barrios LG, Lucas JC (2009). "The Limitations of Good Intent: Problems of Representation and Informed Consent in the Maya ICBG Project in Chiapas, Mexico". In Wynberg R, Schroeder D, Chennells R (eds.). Indigenous Peoples, Consent and Benefit Sharing. Springer Netherlands. pp. 315–331. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3123-5_17. ISBN 978-90-481-3123-5.

- Lavery JV (2007). "Case 1: Community Involvement in Biodiversity Prospecting in Mexico". Ethical Issues in International Biomedical Research: A Casebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 21–43. ISBN 978-0-19-517922-4. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- "A traditional brew leads to cancer cure". Smithsonian Institution: Migrations in history: Medical Technology. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2014-06-21. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Hafstein VT (26 July 2004). "The Politics of Origins: Collective Creation Revisited". Journal of American Folklore. 117 (465): 300–315. doi:10.1353/jaf.2004.0073.

- Karasov C (December 2001). "Focus: who reaps the benefits of biodiversity?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 109 (12): A582-7. doi:10.2307/3454734. JSTOR 3454734. PMC 1240518. PMID 11748021.

- "Method for controlling fungi on plants by the aid of a hydrophobic extracted neem oil". google.com. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Karen Hoggan for the BBC. May 11, 2000 Neem tree patent revoked Archived 2013-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Sheridan C (May 2005). "EPO neem patent revocation revives biopiracy debate". Nature Biotechnology. 23 (5): 511–12. doi:10.1038/nbt0505-511. PMID 15877054.

- BBC News, March 9, 2005 India wins landmark patent battle Archived 2011-06-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Pallottini L, Garcia E, Kami J, Barcaccia G, Gepts P (1 May 2004). "The Genetic Anatomy of a Patented Yellow Bean". Crop Science. 44 (3): 968–977. doi:10.2135/cropsci2004.0968. Archived from the original on 18 April 2005.

- Goldberg D (2003). "Jack and the Enola Bean". TED Case Studies Number xxx. Danielle Goldberg. Archived from the original on 2013-11-10. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- "Rice lines bas 867 rt1117 and rt112". google.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Maharaj, VJ, Senabe, JV, Horak RM (2008). "Hoodia, a case study at CSIR. Science real and relevant". 2nd CSIR Biennial Conference, CSIR International Convention Centre Pretoria, 17&18 November 2008: 4. hdl:10204/2539.

- Wynberg R, Schroeder D, Chennells R (30 September 2009). Indigenous Peoples, Consent and Benefit Sharing: Lessons from the San-Hoodia Case. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-3123-5. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Vermeylen S (2007). "Contextualizing 'Fair' and 'Equitable': The San's Reflections on the Hoodia Benefit-Sharing Agreement". Local Environment. 12 (4): 423–436. doi:10.1080/13549830701495252.

- Wynberg R (2013-10-13). "Hot air over Hoodia". Grain: Publications: Seedling. Grain. Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- Foster LA (April 2001). "Inventing Hoodia: Vulnerabilities and Epistemic Citizenship in South Africa" (PDF). UCLA Center for the Study of Women: CSW update. UCLA Center for the Study of Women. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-04-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Africa suffers 36 cases of biopiracy". GhanaWeb. Retrieved 31 March 2006.

- "Biopiracy - a new threat to indigenous rights and culture in Mexico" (PDF). Global Exchange. Retrieved 13 October 2005.

- "Biopiracy: the appropriation of indigenous peoples' cultural knowledge" (PDF). New England Law. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- "Know Instances of Patenting on the UES of Medicinal Plants in India". PIB, Ministry of Environment and Forests. May 6, 2010. Archived from the original on May 10, 2010.

- "Department of Commerce: United States Patent and Trademark Office [Docket No. 991027289-0263-02] RIN" (PDF), Federal Register: Notices, Office of the Federal Register of the National Archives and Records Administration, 66 (4), pp. 1092–1099, 2001-01-05, archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-02-24, retrieved 2013-11-04

- Chen JM (2006). "The Parable of the Seeds: Interpreting the Plant Variety Protection Act in Furtherance of Innovation Policy". Notre Dame Law Review. 81 (4): 105–166. SSRN 784189.

- Notman N (August 2012). "Cracking down on wildlife trafficking". Image. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

CBD stating that the benefits arising from the use of genetic resources should be shared in a fair and equitable way (Rau, 2010)

- Finegold DL, Bensimon CM, Daar AS, Eaton ML, Godard B, Knoppers BM, Mackie J, Singer PA (July 2005). "Chapter 15: Conclusion: Lessons for Companies and Future Issues". BioIndustry ethics. Elsevier. pp. 331–354. doi:10.1016/b978-012369370-9/50036-7. ISBN 978-0-12-369370-9.

- "Policy Commissions". International Chamber of Commerce: About ICC. International Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- Shiva V (2007). "Bioprospecting as Sophisticated Biopiracy". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 32 (2): 307–313. doi:10.1086/508502. ISSN 0097-9740.

- Millum J (2010). "How Should the Benefits of Bioprospecting Be Shared?". Hastings Center Report. 40 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1353/hcr.0.0227. ISSN 1552-146X. PMC 4714751. PMID 20169653.

- Eberlee J (2000-01-21). "Assessing the Benefits of Bioprospecting in Latin America" (PDF). IDRC Reports Online. IDRC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-23. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- Bisht TS, Sharma SK, Sati RC, Rao VK, Yadav VK, Dixit AK, Sharma AK, Chopra CS (March 2015). "Improvement of efficiency of oil extraction from wild apricot kernels by using enzymes". Journal of Food Science and Technology. 52 (3): 1543–51. doi:10.1007/s13197-013-1155-z. PMC 4348260. PMID 25745223.

- "India hits back in 'bio-piracy' battle". 2005-12-07. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- Koshy JP (2010-04-28). "CSIR wing objects to Avesthagen patent claim". Companies. Live Mint. Archived from the original on 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- "India Partners with US and UK to Protect Its Traditional Knowledge and Prevent Bio-Piracy" (Press release). Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2010-04-28. Archived from the original on 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

Bibliography and resources

- The Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (United Nations Environment Programme) maintains an information centre which as of April 2006 lists some 3000 "monographs, reports and serials".

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (United Nations Environment Programme), Bibliography of Journal Articles on the Convention on Biological Diversity (March 2006). Contains references to almost 200 articles. Some of these are available in full text from the CBD information centre.

- Shiva V (1997). Biopiracy : The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge. South End Press.

- Chen J (2005). "Biodiversity and Biotechnology: A Misunderstood Relation". Michigan State Law Review. 2005: 51–102. SSRN 782184.

External links

- Out of Africa: Mysteries of Access and Benefit-Sharing – a 2006 report on biopiracy in Africa by The Edmonds Institute

- Cape Town Declaration – Biowatch South Africa

- Genetic Resources Action International (GRAIN)

- Indian scientist denies accusation of biopiracy – SciDev.Net

- African 'biopiracy' debate heats up – SciDev.Net

- Bioprospecting: legitimate research or 'biopiracy'? – SciDev.Net

- ETC Group papers on Biopiracy : Topics include: Monsanto’s species-wide patent on all genetically modified soybeans (EP0301749); Synthetic Biology Patents (artificial, unique life forms); Terminator Seed Technology; etc...

- Who Owns Biodiversity, and How Should the Owners Be Compensated?, Plant Physiology, April 2004, Vol. 134, pp. 1295–1307

- Heald Paul J (2001). "'Your Friend in the Rain Forest': An Essay on the Rhetoric of Biopiracy". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.285177.