Bicycle-sharing system

A bicycle-sharing system, public bicycle scheme,[1] or public bike share (PBS) scheme,[2] is a service in which bicycles are made available for shared use to individuals on a short term basis for a price or free. Many bike share systems allow people to borrow a bike from a "dock" and return it at another dock belonging to the same system. Docks are special bike racks that lock the bike, and only release it by computer control. The user enters payment information, and the computer unlocks a bike. The user returns the bike by placing it in the dock, which locks it in place. Other systems are dockless. For many systems, smartphone mapping apps show nearby available bikes and open docks.

History

The first bike sharing projects were initiated by local community organisations, or as charitable projects intended for the disadvantaged, or to promote bicycles as a non-polluting form of transport, or they were business enterprises to rent out bicycles.

The earliest well-known community bicycle program was started in the summer of 1965[3] by Luud Schimmelpennink in association with the group Provo in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.[4][5][3][6] the group Provo painted fifty bicycles white and placed them unlocked in Amsterdam for everyone to use freely.[7] This so-called White Bicycle Plan (Dutch: Wittefietsenplan) provided free bicycles that were supposed to be used for one trip and then left for someone else. Within a month, most of the bikes had been stolen and the rest were found in nearby canals.[8] The program is still active in some parts of the Netherlands (the Hoge Veluwe National Park; bikes have to stay inside the park). It originally existed as one in a series of White Plans proposed in the street magazine produced by the anarchist group PROVO. Years later, Schimmelpennink admitted that "the Sixties experiment never existed in the way people believe" and that "no more than about ten bikes" had been put out on the street "as a suggestion of the bigger idea". As the police had temporarily confiscated all of the White Bicycles within a day of their release to the public, the White Bicycle experiment had actually lasted less than one month.[9]

Ernest Callenbach's novel Ecotopia (1975) illustrated the idea. In the utopian novel of a society that does not use fossil fuels, Callenbach describes a bicycle sharing system which is available to inhabitants and is an integrated part of the public transportation system.[10]

In an attempt to overcome losses from theft, the next innovation adopted by bike sharing programs was the use of so-called 'smart technology'. One of the first 'smart bike' programs was the Grippa™ bike storage rack system used in Portsmouth's Bikeabout scheme.[11][12][13] The Bikeabout scheme was launched in October 1995 by the University of Portsmouth, UK as part of its Green Transport Plan in an effort to cut car travel by staff and students between campus sites.[12] Funded in part by the EU's ENTRANCE[14] program, the Bikeabout scheme was a "smart card" fully automated system.[12][13][15] For a small fee, users were issued 'smart cards' with magnetic stripes to be swiped through an electronic card reader at a covered 'bike store' kiosk, unlocking the bike from its storage rack.[12] CCTV camera surveillance was installed at all bike stations in an effort to limit vandalism.[12] Upon arriving at the destination station, the smart card was used to open a cycle rack and record the bike's safe return.[12] A charge was automatically registered on the user's card if the bike was returned with damage or if the time exceeded the three-hour maximum.[12] Implemented with an original budget of approximately £200,000, the Portsmouth Bikeabout scheme was never very successful in terms of rider usage,[16] in part due to the limited number of bike kiosks and hours of operation.[12][15] Seasonal weather restrictions and concerns over unjustified charges for bike damage also imposed barriers to usage.[12] The Bikeabout program was discontinued by the University in 1998 in favor of expanded minibus service; the total costs of the Bikeabout program were never disclosed.[17][18]

In 1995 a system of 300 bicycles using coins to unlock the bicycles in the style of shopping carts was introduced in Copenhagen. It was initiated by Morten Sadolin and Ole Wessung. The idea was developed by both Copenhageners after they were victims of bicycle theft one night in 1989.[19] Copenhagen's ByCylken program was the first large-scale urban bike share program to feature specially designed bikes with parts that could not be used on other bikes. To obtain a bicycle, riders pay a refundable deposit at one of 100 special locking bike stands, and have unlimited use of the bike within a specified 'city bike zone'.[20] The fine for not returning a bicycle or leaving the bike sharing zone exceeds US$150, and is strictly enforced by the Copenhagen police. Originally, the program's founders hoped to completely finance the program by selling advertising space on the bicycles, which was placed on the bike's frame and its solid disc-type wheels. This funding source quickly proved to be insufficient, and the city of Copenhagen took over the administration of the program, funding most of the program costs through appropriations from city revenues along with contributions from corporate donors. Since the City Bikes program is free to the user, there is no return on the capital invested by the municipality, and a considerable amount of public funds must constantly be re-invested to keep the system in service, to enforce regulations, and to replace missing bikes.

One of the first community bicycle projects in the United States was started in Portland, Oregon in 1994 by civic and environmental activists Tom O'Keefe, Joe Keating and Steve Gunther. It took the approach of simply releasing a number of bicycles to the streets for unrestricted use. While Portland's Yellow Bike Project was successful in terms of publicity, it proved unsustainable due to theft and vandalism of the bicycles. The Yellow Bike Project was eventually terminated, and replaced with the Create A Commuter (CAC) program, which provides free secondhand bicycles to certain preselected low-income and disadvantaged people who need a bicycle to get to work or attend job training courses.[21] Since 1994, many community projects around the country have attempted programs similar in nature to the Yellow Bike Project, most of which have since been abandoned.

Bike share technology has evolved over the course of decades, and development of programs in Asia has grown exponentially. Of the world's 15 biggest public bike share programs, 13 are in China. In 2012, the biggest are in Wuhan and Hangzhou, with around 90,000 and 60,000 bikes respectively.[22]

Categorisation

Bike-sharing systems have developed and evolved with society changes and technological improvements. The systems can be grouped into five categories or generations. Many bicycle programmes paint their bicycles in a strong solid colour, such as yellow or white. Painting the bicycles helps to advertise the programme, as well as deter theft (a painted-over bicycle frame is normally less desirable to a buyer). However, theft rates in many bike-sharing programmes remain high, as most shared-use bicycles have value only as basic transport, and may be resold to unsuspecting buyers after being cleaned and repainted. In response, some large-scale bike sharing programmes have designed their own bike using specialised frame designs and other parts to prevent disassembly and resale of stolen parts.

Staffed stations

- Short-term checkout

Also known as bicycle rental, bike hire or zero generation. In this system a bicycle can be rented or borrowed from a location and returned to that location. These bicycle renting systems often cater to day-trippers or tourists. This system is also used by cycling schools for potential cyclists who don't have a bicycle. The locations or stations are not automated but are run by employees or volunteers.

Regional programs have been implemented where numerous renting locations are set up at railway stations and at local businesses (usually restaurants, museums and hotels) creating a network of locations where bicycles can be borrowed from and returned (e.g. ZweiRad FreiRad with at times 50 locations[23]). In this kind of network for example a railway station master can allocate a bicycle to a user that then returns it at a different location, for example a hotel. Some such systems require paying a fee, and some do not. Usually the user will be registered or a deposit will be left by the renting facility. The EnCicla Bike Share System in Medellín on its inception in 2011 had 6 staffed locations. It later grew to 32 automatic and 19 staffed stations making it a hybrid between a zero generation and third generation system.

- Long-term checkout

Sometimes known as bike library systems, these bicycles may be lent free of charge, for a refundable deposit, or for a small fee. A bicycle is checked out to one person who will typically keep it for several months, and is encouraged or obliged to lock it between uses. A disadvantage is a lower usage frequency, around three uses per day on average as compared to 2 to 15 uses per day typically experienced with other bike-sharing schemes. Advantages of long-term use include rider familiarity with the bicycle, and constant, instant readiness.

The bicycle can be checked out like a library book, a liability waiver can be collected at check-out, and the bike can be returned any time. For each trip, a Library Bike user can choose the bike instead of a car, thus lowering car usage. The long-term rental system generally results in fewer repair costs to the scheme administrator, as riders are incentivised to obtain minor maintenance in order to keep the bike in running order during the long rental period. Most of the long-term systems implemented to date are funded solely through charitable donations of second-hand bicycles, using unpaid volunteer labour to maintain and administer the bicycle fleet. While reducing or eliminating the need for public funding, such a scheme imposes an outer limit to program expansion. The Arcata Bike Library, in California, has loaned over 4000 bicycles using this system.

White bikes

Also known as free bikes, unregulated or first generation. In this type of programme the bicycles are simply released into a city or given area for use by anyone. In some cases, such as a university campus, the bicycles are only designated for use within certain boundaries. Users are expected to leave the bike unlocked in a public area once they reach their destination. Depending on the quantity of bicycles in the system availability of such bicycles can suffer because the bikes are not required to be returned to a centralised station. Such a system can also suffer under distribution problems where many bicycles end up in a valley of a city but few are found on the hills of a city. Since parked and unlocked bikes may be taken by another user at any time, the original rider might have to find an alternative transport for the return trip. This system does away with the cost of having a person allocating a vehicle to a user and it is the system with the lowest hemmschwelle or psychological barrier for a potential user. However, bicycle sharing programs without locks, user identification, and security deposits have also historically suffered loss rates from theft and vandalism. Many initiatives have been abandoned after a few years (e.g. Portland's Yellow Bike Project was abandoned after 3 years[24]), while others have been successful for decades (e.g. Austin's Yellow Bike Project active since 1997[25]). Most of these systems are based around volunteer work and are supported by municipalities. Bicycle repair and maintenance are done by a volunteer project or from the municipality contracted operator but also can be, and sometimes is, completed by individual users who find a defect on a free bike.

Coin deposit stations

Also known as Bycykel or as second generation, this system was developed by Morten Sadolin and Ole Wessung of Copenhagen after both were victims of bicycle theft one night in 1989.[26] They envisioned a freely available bicycle sharing system that would encourage spontaneous usage and also reduce bicycle theft. The bicycles, designed for intense utilitarian use with solid rubber tires and wheels with advertising plates, have a slot into which a shopping cart return key can be pushed. A coin (in most versions a 20 DKK or 2 EUR coin) needs to be pushed into the slot to unlock the bike from the station. The bicycle can thus be borrowed free of charge and for an unlimited time and the deposit coin can be retrieved by returning the bicycle to a station again. Since the deposit is a fraction of the bike's cost, and user is not registered this can be vulnerable to theft and vandalism. However, the distinct Bycykel design, well known to the public and to the law authorities does deter misuse to a degree. Implemented systems usually have a zone or area where it is allowed to drive in. The first coin deposit (small) systems were launched in 1991 in Farsø and Grenå, Denmark, and in 1993 in Nakskov, Denmark with 26 bikes and 4 stations. In 1995 the first large-scale 800 bike strong second generation bike-sharing program was launched in Copenhagen as Bycyklen.[27] The system was further introduced in Helsinki (2000-2010) and Vienna in (2002) and in Aarhus[28] 2003.

Automated stations

Also known as docking stations bicycle-sharing, or membership bicycles or third generation consist of bicycles that can be borrowed or rented from an automated station or "docking stations" or "docks" and can be returned at another station belonging to the same system. The docking stations are special bike racks that lock the bike, and only release it by computer control. Individuals registered with the program identify themselves with their membership card (or by a smart card, via cell phone, or other methods) at any of the hubs to check out a bicycle for a short period of time, usually three hours or less. In many schemes the first half-hour is free. In recent years, in an effort to reduce losses from theft and vandalism, many bike-sharing schemes now require a user to provide a monetary deposit or other security, or to become a paid subscriber. The individual is responsible for any damage or loss until the bike is returned to another hub and checked in.

This system was developed as Public Velo by Hellmut Slachta and Paul Brandstätter from 1990 to 1992, and first implemented by the University of Portsmouth and Portsmouth City Council as Bikeabout in 1996 and in Rennes as LE vélo STAR. The smart card contactless technology was experimented in Vienna (Citybike Wien) and in 2005 at a large scale in Lyon (Vélo'v) and in 2007 in Paris (Vélib'). Since then over 1000 bicycle sharing system of this generation have been launched.[29] The countries with the most dock based systems are Spain (132), Italy (104), and China (79).[7][5] As of June 2014, public bike share systems were available in 50 countries on five continents, including 712 cities, operating approximately 806,200 bicycles at 37,500 stations.[30][31] As of May 2011, the Wuhan and Hangzhou Public Bicycle bike-share systems in China were the largest in the world, with around 90,000 and 60,000 bicycles respectively.[7] By 2013, China had a combined fleet of 650,000 public bikes.[32]

This bicycle-sharing system saves the labour costs of staffed stations (zero generation), reduces vandalism and theft compared to first and second generation systems by registering users but requires a higher investment for docking stations compared to the fourth generation dockless bikes. The third generations hold an advantage over fourth generation systems by being able to adapted docking stations into E-bike recharging stations for E-bike sharing.[33][34]

Dockless bikes

Also known as Call a Bike, free floating bike or fourth generation, the dockless bike hire systems consist of a bicycle with a lock that is usually integrated onto the frame and does not require a docking station. The earliest versions of this system consisted of for-rent-bicycles that were locked with combination locks and that could be unlocked by a registered user by calling the vendor to receive the combination to unlock the bicycle. The user would then call the vendor a second time to communicate where the bicycle had been parked and locked. This system was further developed by Deutsche Bahn in 1998 to incorporate a digital authentication codes (that changes) to automatically lock and unlock bikes. Deutsche Bahn launched Call a Bike in 2000, enabling users to unlock via SMS or telephone call, and more recently with an app.[35] Recent technological and operational improvements by telephones and GPSs have paved the way for dramatic increase of this type of private app driven "dockless" bicycle-sharing system. In particular in China, Ofo and Mobike have become the world's largest bike share operators with millions of bikes spread over 100 cities.[36] Today dockless bike shares are designed whereby a user need not return the bike to a kiosk or station; rather, the next user can find it by GPS.[37][38][39] Over 30 private companies have started operating in China.[40][41] However, the rapid growth vastly outpaced immediate demand and overwhelmed Chinese cities, where infrastructure and regulations were not prepared to handle a sudden flood of millions of shared bicycles.[42]

Due to the fact that this system does not require docking stations and thus does not need built infrastructure that may require city planning and building permissions, the system has spread rapidly on a global scale,.[43] At times dockless bike-sharing systems have been criticized as rogue systems instituted without respect for local authorities.[44] In many cities were entrepreneurial companies have independently introduced this bicycle sharing system, adequate parking facilities for bikes are missing, city officials lack regulation experience for this mode of transportation and social habits have not developed either. In some jurisdictions, authorities have confiscated "rogue" dockless bicycles that are improperly parked for potentially blocking pedestrian traffic on sidewalks[45] and in other cases new laws have been introduced to regulate the shared bikes.

In some cities Deutsche Bahn's Call a Bike has Call a Bike fix system, which has fixed docking stations versus the flex dockless version, some systems are combined into a hybrid of third and fourth generation systems. Some Nextbike systems are also a 3rd and 4th generation hybrid. With the arrival of dockless bike shares, there are now over 70 private dockless bikeshares operating a combined fleet of 16 million sharebikes according to estimates of Ministry of Transport of China.[46][47] Beijing alone has 2.35 million sharebikes from 15 companies.[48]

In the United States, many major metropolitan areas are experimenting with dockless bikeshare systems, which have been popular with commuters but subject to complaints about illegal parking.[49]

Goals of bike sharing

The reasons and goals of Bike-sharing vary but can be grouped into the following Most large-scale urban bike sharing programmes utilise numerous bike check-out stations, and operate much like public transit systems, catering to tourists and visitors as well as local residents. Their central concept is to provide free or affordable access to bicycles for short-distance trips in an urban area as an alternative to motorised public transport or private vehicles, thereby reducing congestion, noise, and air pollution. Bicycle-sharing systems have also been cited as a way to solve the "last mile" problem and connect users to public transit networks.[50]

People use bike-share for various reasons. Some who would otherwise use their own bicycle have concerns about theft or vandalism, parking or storage, and maintenance.[51][52] However, dock systems, serving only stations, resemble public transit, and have therefore been criticized as less convenient than a privately owned bicycle used door-to-door.[53]

Operation

Bicycle-sharing systems are an economic good, and are generally classified as a private good due to their excludable and rivalrous nature. While some bicycle-sharing systems are free, most require some user fee or subscription, thus excluding the good to paying consumers. Bicycle-sharing systems also provide a discrete and limited number of bikes, whose distribution can vary throughout a city. One person's usage of the good diminishes the ability of others to use the same good. Nonetheless, the hope of many cities is to partner with bike-share companies to provide something close to a public good.[54] Public good status may be achieved if the service is free to consumers and there are a sufficient number of bicycles such that one person's usage does not encroach upon another's use of the good.

Partnership with public transport sector

In a national-level programme that combines a typical rental system with several of the above system types, a passenger railway operator or infrastructure manager partners with a national cycling organisation and others to create a system closely connected with public transport. These programmes usually allow for a longer rental time of up to 24 or 48 hours, as well as tourists and round trips. In some German cities the national rail company offers a bike rental service called Call a Bike.

In Guangzhou, China, the privately operated Guangzhou Bus Rapid Transit system includes cycle lanes, and a public bicycle system.[55]

In some cases, like Santander Cycles in London, the bicycle sharing system is owned by the public transport authority itself.

In other cases, like EnCicla in the city of Medellin (Colombia, South America), the Bicycle Sharing System is connected to other modes of transportation, such as the Metro.[56]

Partnership with car park operators

Some car park operators such as Vinci Park in France lend bikes to their customers who park a car.[57]

Partnership with car-share operations

City CarShare, a San Francisco-based non-profit, received a federal grant in 2012 to integrate electric bicycles within its existing car-sharing fleet. The program is set to launch before the end of 2012 with 45 bikes.[58]

Financing

The financing of bicycle-sharing system have been maintained by a combination of fees, volunteer, charity, advertisements, business interest groups and government subsidies. The international expansion dockless bicycles in mid 2010s has been financed by investment capital.

User fees

User rent fees may range from the equivalent of US$0.50 to 30.00 per day, rent fees for 15- or 20-minute intervals can range from a few cents to 1.00. Many bike-share systems offer subscriptions that make the first 30–45 minutes of use either free or very inexpensive, encouraging use as transportation. This allows each bike to serve several users per day but reduces revenue. Monthly or yearly membership subscriptions and initial registration fees may apply. To reduce losses from theft often users are required to commit to temporary deposit via a credit card or debit card. If the bike is not returned within the subscription period, or returned with significant damage, the bike sharing operator keeps the deposit or withdraws money from the user's credit card account. operated by private companies as is the case in most cities in China.[59]

US

New York rental rates are among the highest in the world, as of the Citi Bike program's launch in July of 2012, but this is of course subject to change.[60] The cost of annual membership in the US varies between $100 and about $170.[61]

Europe

Bike riders shared in Europe usually pay between €0.50 to €1 per trip, and an average of €10-12 for a full day cycling.

Volunteer work

Many first and second generation bicycle sharing programs were and are community run organisations as "Community Bike programmes", as done in IIT Bombay. Often maintenance and repair is performed by unpaid volunteers that complete this work in their own free time.

Charity sources

Charity fundraising drives and charitable organisations have and do support bicycle sharing programs, including Rotary Clubs and Lions Clubs.

Advertisement revenue

Second and third generation schemes in the 90s already prominently included advertising opportunities on the individual bikes in form of advertisement areas on the wheels or frame. Other schemes are completely branded according to a sponsor, notable example London's bike share which was originally branded and sponsored by Barclays Bank and subsequently by Santander UK Several European cities, including the French cities of Lyon and Paris as well as London, Barcelona, Stockholm and Oslo, have signed contracts with private advertising agencies (JCDecaux in Brussels, Lyon, Paris, Seville, Dublin and Oslo; Clear Channel in Stockholm, Barcelona, Antwerp, Perpignan and Zaragoza) which supply the city with thousands of bicycles free of charge (or for a minor fee). In return, the agencies are allowed to advertise both on the bikes themselves and in other select locations in the city. typically in the form of advertising on stations or the bicycles themselves.

Government subsidies

Municipalities have operated and do operate bicycle share systems as a public service, paying for the initial investment, maintenance and operations if it is not covered by other revenue sources. Governments can also support

bicycle share programs in forms of one time grants (often to buy a set of bicycles), yearly of monthly subsidies, or by paying part of the employee wages (example in repair workshops that employee long-term unemployed persons). Many of the membership-based systems are operated through public-private partnerships. Some schemes may be financed as a part of the public transportation system (for example Smoove). In Melbourne the government subsidises the sale of bicycle helmets[62] to enable spontaneous cyclists comply with the mandatory helmet laws.

Harvesting of user-data

GPS traceable vehicle commute patterns and usage habits present valuable data for government agencies, marketing companies or researchers. Strong commuter patterns can be filtered out and potential transportation services (e.g. commuter bus) can be tailored to existing demand. Potential audiences can be better assessed and understood.

Usage patterns

Another advantage of bike-sharing systems is that the smart-cards allow the bicycles to be returned to any station in the system, which facilitates one-way rides to work, education or shopping centres. Thus, one bike may take 10–15 rides a day with different users and can be ridden up to 10,000 km (6,200 mi) a year (citing Lyon, France). Each bike has at least one of these rides with one unique user per day which indicates that in 2014 there were a minimum of at least 294 million unique bike share cyclists worldwide (806,200 bicycles x 365) although common sense indicates that this figure may be a very small estimate of the true number of bike share users.[63]

It was found—in cities like Paris and Copenhagen—that to have a major impact there had to be a high density of available bikes. Copenhagen has 2500 bikes which cannot be used outside the 9 km2 (3.5 sq mi) zone of the city centre (a fine of DKr 1000 applies to any user taking bikes across the canal bridges around the periphery). Since Paris's Vélib' programme operates with an increasing fee past the free first half-hour, users have a strong disincentive to take the bicycles out of the city centre. The distance between stations is only 300–400 metres (1,000–1,300 ft) in inner city areas.

in US, bike sharing is still a male-dominated space where male users made up for more than 80% of total trips made in 2017.

A study published in 2015 in the journal Transportation concludes that bike sharing systems can be grouped into behaviourally similar categories based upon their size.[65] Cluster analysis shows that larger systems display greater behavioural heterogeneity amongst their stations, and smaller systems generally have stations which all behave similarly in terms of their daily utilisation patterns.

Global distribution of bike-sharing systems

Economic impact

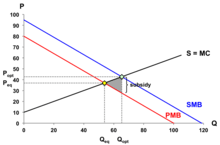

Bike-share programs generate a number of economic externalities, both positive and negative. The positive externalities include reduction of traffic congestion and pollution, while the negative externalities can include degradation of urban aesthetic environment and reduction of parking. Furthermore, bike-share programs have pecuniary effects. Some of these economic externalities (e.g. reduced congestion) can be systematically evaluated using empirical data, and therefore may be internalized through government subsidy. On the other hand, "nuisance" externalities (e.g. street and sidewalk clutter) are more subjective and harder to quantify, and may not be able to be internalized.

Positive externalities

Reduction of traffic congestion

A primary goal of bicycle-sharing systems has been to reduce traffic congestion, particularly in large urban areas. Some empirical evidence indicates that this goal has been achieved to varying degrees in different cities. A 2015 article in Transport Reviews examined bike-share systems in five cities, including Washington, D.C. and Minneapolis. The article found that in D.C., individuals substituted bike-share rides for automobile trips 8 percent of the time, and almost 20 percent of the time in Minneapolis.[66] A separate study on Washington, D.C.'s Capital Bikeshare found that the bike-share program contributed a 2 to 3 percent reduction in traffic congestion within the evaluated neighborhood.[67] 2017 studies in Beijing and Shanghai have linked the massive increase of dockless bike shares to the decrease in the number of private automobile trips that are less than five kilometres.[68] In Guangzhou, the arrival of dockless bike shares had a positive impact in the growth of cycling modeshare.[69]

Reduction of pollution

Not only do bike-share systems intend to reduce traffic congestion, they also aim to reduce air pollution through decreased automobile usage, and indrectly through the reduction of congestion. The study on D.C.'s Capital Bikeshare estimated that the reduction in traffic congestion would be equivalent to roughly $1.28 million in annual benefits, accrued through the reduction in congestion-induced CO2 emissions.[67] A separate study of transportation in Australia estimated that 1.5 kilograms of CO2 equivalent emissions are avoided by an urban resident who travels 5 kilometers by cycling rather than by car during rush hour periods.[70]

Healthy transport

Bicycle-sharing systems have been shown to have a strong net positive health effect.[71] Cycling is a good way for exercise and stress relief. It can increase recreation and improve sociability of a city, which make people live more happy and relaxed. The report from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) point out that cycling also help preventing disease like obesity, heart disease (can reduce up to 82%) and diabetes (can reduce up to 58%). Therefore, bicycle-sharing systems has a positive effect on mental and physical health, which attract more people to use. (Demand increase)[72]

Negative externalities

Reduced car parking

Bike-share programs, especially the earlier services that required docking areas along urban streets, may encroach upon the space available for on-street car parking and other uses. Some urbanists argue that this is actually a positive side effect, since it helps further the transition away from car-dependency.[73]

Urban clutter

In some cities, the many dockless bike-share bicycles have cluttered streets and sidewalks, degrading the urban aesthetic environment and blocking pedestrian traffic. In particular, cycles on Chinese city streets have created sections of clogged sidewalks no longer walkable, and piles of illegally parked bicycles.[74]

Due to the vehicles being left in the public right of way, or abandoned obstructing pedestrians, the dockless vehicles have been called "litter bikes".[75]

Dockless cycles left randomly on public footpaths may impede access for wheelchair users and others who use mobility aids, and may be dangerous to people with visual impairments.[76]

Pecuniary effects

As bicycle-sharing systems continue to grow and provide an affordable alternative for commuters, the relatively low price of these services may induce competitors to offer lower prices. For instance, municipal public transit organizations may lower prices for buses or subways to continue to compete with bike-share systems. Pecuniary effects may even extend to bicycle manufacturers and retailers, where these producers might reduce prices of bicycles and other complementary goods (e.g. helmets, lights). However, empirical research is needed to test these hypotheses.

Safety

As most of the dockless bikes system do not provide helmet for riders, the proportion of head injuries that related to bicycle increased.[77] Without providing a helmet with the bikes, it increases the risk of using the bicycle-sharing system, even the bicycle companies encourage rider to prepare one.[78] "Safety first." In order to transport from one place to the other, people will pick the fastest and safest way to travel. Therefore, the risk of injury might decrease the number of people who use the bicycle-sharing system, which cause a decrease in demand.

Internalization of externalities

Public-private partnerships

In public economics, there is a role for government intervention in a market if market failures exist, or in the case of redistribution. As several studies have found, bike-share programs appear to produce net positive externalities in reduced traffic congestion and pollution, for example.[79][67] The bike-sharing market does not produce at the social optimum, justifying the need for government intervention in the form of a subsidy for the provision of this good in order to internalize the positive externality. Many cities have adopted public-private partnerships to provide bike-shares, such as in Washington, D.C. with Capital Bikeshares.[80] These partially government-funded programs may serve to better provide the good of bike-shares.

Dangers of over-supply

Many bike-share companies and public-private partnerships aim to supply shared bicycles as a public good. In order for bike-shares to be a public good, they must be both non-excludable and non-rival. Numerous bike-share programs already offer their services partly for free or at least at very low prices, therefore nearing the non-excludable requirement.[20] However, in order to achieve the non-rival requirement, shared bicycles must be supplied at a certain density within an urban area. There are numerous challenges with attaining non-rivalry, for instance, redistribution of bicycles from low-demand regions to regions with high-demand.[81] Mobike, a China-based company, is attempting to solve this problem by paying their users to ride their bikes from low-demand areas to high-demand areas.[82] Other companies such as OBike have introduced a points system to penalize negative behavior, namely, illegal parking of shared bicycles.[83] Economists speculate that a combination of efficient pricing with well-designed regulatory policies could significantly mitigate problems of over-supply and clutter.[84]

The Chinese bicycle-sharing market demonstrated the danger of oversupply in 2018. Companies took advantage of unclear regulations in the preceding years to introduce millions of shared bikes to the country's cities. Users were not educated in how to use the systems properly and in many cases treated them as disposable, parking them anywhere. City governments were forced to impound the abandoned bikes when they blocked public thoroughfares, and millions of bikes went directly to junkyards after the companies that owned them went bankrupt.[85][86]

Health impacts

A study published in the American Journal of Public Health reports observing[79] an increase in cycling and health benefits where bicycle sharing systems are run. In the United States, bikesharing programs have proliferated in recent years, but collision and injury rates for bikesharing are lower than previously computed rates for personal bicycling; at least two people have been killed while using a bike share scheme.[87][88][89]

There is also considerable evidence that bike-share programs must be adopted in tandem with city infrastructure, namely, the creation of bike lanes. A 2012 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that Toronto's cyclists were 30-50% more likely to be involved in an accident on major roads without cycle lanes than on those with.[90]

Criticism

Despite their theoretical and observed benefits, bike-share programs have come under attack as their presence has grown throughout the world. Much of this criticism has focused on the use of public funding - concerned critics posit that the use of tax money for bike-share programs should instead be diverted towards building or maintaining roads and other services that more residents use on a daily basis.[91] However, this argument relies on a faulty assumption that taxpayer money is a significant source of bike-share funding. An analysis by People for Bikes, an organization that advocates for new and safe bike infrastructure, found that public investment in Salt Lake City's Greenbike and Denver's B-Cycle programs was significantly less than traditional public transit (e.g. bus or rail) in those same cities, on a per-trip basis. Both Greenbike and B-Cycle's publicly funded subsidies amount to 10 percent or less of the total cost of one trip.[92] In contrast, Salt Lake City's’s bus and rail system (UTA) relies on 80 percent public funding for a single trip.[92]

Other critics claim that bike-share programs fail to reach more low-income communities.[93] Some efforts have attempted to address this issue, such as New York City's Citi Bike's discounted membership program, which is aimed at increasing ridership among low-income residents. However, around 80 percent of study respondents reported that they had no knowledge of the program's discount.[93]

See also

Notes

References

- Kodukula, Santhosh (September 2010). "Recommended Reading and Links on Public Bicycle Schemes" (PDF). European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- mattlamy (18 June 2019). "A guide to hire bikes and public bike share schemes". Cycling UK.

- "Runde Sache". Readers Digest Deutschland (in German). 06/11: 74–75. June 2011.

- Furness, Zack (2010). One Less Car: Bicycling and the Politics of Automobility. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 55–59. ISBN 978-1-59213-613-1.

- Bike-Sharing Programs Hit the Streets in Over 500 Cities Worldwide; Earth Policy Institute; Larsen, Janet; 25 April 2013

- Marshall, Aarian (3 May 2018). "Americans Are Falling in Love With Bike Share". Transportation. WIRED. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

The first bike-share systems, starting in 1960s Amsterdam....

- Susan Shaheen & Stacey Guzman (Fall 2011). "Worldwide Bikesharing". Access Magazine No. 39. University of California Transportation Center. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- Shirky, Clay Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations (2008.) Penguin. pg 282-283

- Moreton, Cole (16 July 2000). "Reportage: The White Bike comes full circle" (Reprint). The Independent. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- Callenbach, Ernest (1975). Ecotopia. Ernest Callenbach (first self-published as Banyan Tree Books). p. 181. ISBN 978-0-553-34847-7.

- Cycle Security - VeloTron

- Black, Colin, Faber, Oscar, and Potter, Stephen, Portsmouth Bikeabout: A Smart-Card Bike Club Scheme, The Open University (1998)

- DeMaio, Paul, and Gifford, Jonathan, Will Smart Bikes Succeed as Public Transportation in the United States, Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 7, No. 2, (2004) p. 6

- Acronym for the ENergy savings in TRANsport through innovation in the Cities of Europe programme

- Hoogma, Remco, et al, Experimenting For Sustainable Transport: The approach of Strategic Niche Management, London: Spon Press, ISBN 020399406X (2002), pp. 4-11, 176

- The Portsmouth Bikeabout program never exceeded 500 users at any time during its operational existence.

- University of Portsmouth Academic Staff Association, Minutes of ASA Executive Meeting, 20 October 1999

- University of Portsmouth Academic Staff Association, Meeting of ASA Executive, Annexe: presentation by Pro-Vice Chancellor Mike Bateman on mobility policy, 16 January 2002

- Alsvik, Arild. "Bysyklene" (PDF). uio.no. Universitetet i Oslo. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Free City Bike Schemes, Søren B. Jensen, City of Copenhagen, Conference Proceedings, Amsterdam 2000

- Law, Steve, People in Need Offered Free Bikes, The Portland Tribune, 20 January 2011: Originally, CAC handed out free bicycles to any low-income applicant; this was changed after many of the CAC bicycles began appearing for resale in classified advertisements.

- (PDF) https://rep.bntu.by/bitstream/handle/data/27516/Bicycle%20sharing%20system.pdf?sequence=1. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Freiradln". Radland.at. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 25 May 018.

- LISA TOZZI (17 October 1997). Austin Chronicle. Ride On, Yellow Bikes https://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1997-10-17/518610/. Retrieved 25 May 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Yellow Bikes". Austin Yellow Bikes. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Alsvik, Arild. "Bysyklene" (PDF). uio.no. Universitetet i Oslo. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- DeMaio, Paul (2009). "Bike-sharing: History, Impacts, Models of Provision, and Future". Journal of Public Transportation. 12 (4, 2009).

- "English: Aarhus Bycykel". www.aarhus.dk.

- "The Bike-sharing World Map is 10 years old". Bike-Sharing.blogspot.com. 9 November 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Susan A. Shaheen; et al. (October 2015). "Public Bikesharing in North America During a Period of Rapid Expansion: Understanding Business Models, Industry Trends and User Impacts" (PDF). Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI). Retrieved 5 November 2014. pp. 5

- "Urban planning - Streetwise". The Economist. Gurgaon, India. 5 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Wang, Yue. "Return of Bicycle Culture in China Adds To Billionaires' Wealth". Forbes. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- "Bicycle Sharing, Renting & Parking".

- "Bike Sharing Gets an Electric Update".

- "Call a Bike - die Mietfahrräder der Bahn". bahn.de. Deutsche Bahn. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "Why China's bike-sharing boom is causing headaches". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- Gizmag SoBi bicycle sharing system

- "viaCycle: How it Works". viaCycle. December 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- "Bike Sharing Program Rolls on Campus during Summer". Georgia Tech News Room. 20 June 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Fannin, Rebecca. "Bike Sharing Apps in China Pop Up As Latest Startup And Unicorn Craze". Forbes. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- "China's bicycle-sharing boom poses hazards for manufacturers". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- Taylor, Alan. "The Bike-Share Oversupply in China: Huge Piles of Abandoned and Broken Bicycles". The Atlantic. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "Dockless bike sharing will reshape cities, says Dublin start-up". Bikebiz. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Sisson, Patrick (31 March 2017). "Is dockless bikeshare the future of urban transit?". Curbed. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Iannelli, Jerry (13 July 2017). "Miami Beach Cracks Down on "Rogue" Bike-Sharing Startup LimeBike". Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Simply Put: In China's bikeshare success, peek into big data potential". The Indian Express. 2 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- Reuters. "Bike Boom Nibbles on Asia Gasoline Demand Growth". VOA. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "Beijing issues guideline on bike sharing - Xinhua | English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- Lazo, Luz (31 August 2018). "D.C. allows dockless bikes and scooters to stay, but you'll have to start locking them up". Washington Post. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- "In Focus: The Last Mile and Transit Ridership". Institute for Local Government. January 2011.

- Shaheen, Susan; Guzman, S.; Zhang, H. (2010). "Bikesharing in Europe, the Americas, and Asia: Past, Present, and Future". Transportation Research Record. 2143: 159–167. doi:10.3141/2143-20.

- "Mobiped". Mobiped. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 22 September 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- James May (21 October 2010). "May, James, Cycling Proficiency With James May, The Daily Telegraph, 21 October 2010". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Bieler, Andrew (December 2008). "Bikes as a Public Good: What is the Future of Public Bike Sharing in Toronto" (PDF). Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- "Public Bicycles to Run on BRT System (Guangzhou): lifeofguangzhou.com, quoting english.gz.gov.cn, 19 Mar 2010". Lifeofguangzhou.com. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Bejarano, Mauricio; Ceballos, Lina M.; Maya, Jorge (1 January 2017). "A user-centred assessment of a new bicycle sharing system in Medellin". Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 44: 145–158. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2016.11.004.

- "réinventons le stationnement". VINCI Park. Archived from the original on 5 March 2005. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Garthwaite, Josie (6 February 2012). "A Bay Area Experiment in Electric Bike Sharing". New York Times. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- McCabe, Bret (18 April 2016). "Bike sharing: JHU alum's new book explores how the bicycle reshaped life in America". Johsn Hopkins University News. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Salmon, Felix (7 May 2012). "New York's expensive bikeshare". Reuters Blogs. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Citi Bike Membership & Pass Options". Citi Bike NYC. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Lucas, Clay, Helmet Law Hurting Shared Bike Scheme, The Age, 29 November 2010". Melbourne: Theage.com.au. 29 November 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- "Some cycling statistics". EESC Glossaries. 21 May 2019.

- "Link Bike". www.linkbike.my. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Sarkar, Advait; Lathia, Neal; Mascolo, Cecilia (2015). "Comparing cities' cycling patterns using online shared bicycle maps". Transportation. 42 (4): 541–559. doi:10.1007/s11116-015-9599-9.

- Fishman, Elliot (April 2015). "Bikeshare: A Review of Recent Literature". Transport Reviews. 36: 92–113. doi:10.1080/01441647.2015.1033036.

- Hamilton, Timothy; Wichman, Casey (20 August 2015). "Bicycle Infrastructure and Traffic Congestion: Evidence from DC's Capital Bikeshare". SSRN 2649978. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Time to regulate China's booming bike share sector". www.chinadialogue.net. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Dockless bike sharing renders old model obsolete". www.fareastbrt.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Bonham, Jennifer (2005). "Economics of everyday cycling and cycling facilities". Cycling Futures. JSTOR 10.20851.

- Woodcock, James; Tainio, Marko; Cheshire, James; O’Brien, Oliver; Goodman, Anna (13 February 2014). "Health effects of the London bicycle sharing system: health impact modelling study". BMJ. 348: g425. doi:10.1136/bmj.g425. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 3923979. PMID 24524928.

- "Bike Share Feasibility Study". The City of Wilmington: 21–27. Spring 2016.

- Garthwaite, Josie (14 July 2011). "To Curb Driving, Cities Cut Down on Car Parking". National Geographic News. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Haas, Benjamin (25 November 2017). "Chinese bike share graveyard a monument to industry's 'arrogance'". the Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Cities vow to crack down on "litter bikes"". CBS News. United States. 30 April 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Dockless bikes impounded by council for "blocking parking spaces"".

- "Bike sharing: Research on health effects, helmet use and equitable access". Journalist's Resource. 5 April 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "Who is responsible for helmets when it comes to bike shares?". SFGate. 30 August 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Daniel Fuller; Lise Gauvin; Yan Kestens; Mark Daniel; Michel Fournier; Patrick Morency & Louis Drouin (17 January 2013). "mpact Evaluation of a Public Bicycle Share Program on Cycling: A Case Example of BIXI in Montreal, Quebec". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (3): e85–e92. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300917. PMC 3673500. PMID 23327280.

- "Capital Bikeshare Launches in Alexandria". Capital Bikeshare. 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- Xie, Xiao-Feng; Wang, Zunjing (2018). "Examining travel patterns and characteristics in a bikesharing network and implications for data-driven decision supports: Case study in the Washington DC area". Journal of Transport Geography. 71: 84–102. arXiv:1901.02061. Bibcode:2019arXiv190102061X. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.07.010.

- Horwitz, Josh. "One of China's top bike-sharing startups is now paying users to ride its bikes". Quartz. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "Tech in Asia - Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem". www.techinasia.com. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "The Sharing Economy is Learning How to Ride a Bike". Energy Institute Blog. 20 February 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Taylor, Alan (22 March 2018). "The Bike-Share Oversupply in China: Huge Piles of Abandoned and Broken Bicycles". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "The unexpected beauty of China's Bicycle Graveyards". The Guardian. 1 May 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Martin, Elliot; Cohen, Adam; Botha, Jan; Shaheen, Susan (March 2016). Bikesharing and Bicycle Safety (PDF) (Technical report). Mineta Transportation Institute. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Williams-Harris, Deanese; Wisniewski, Mary (3 July 2016). "Woman killed in crash believed to be 1st bike-sharing death in U.S." Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- "Cyclist Killed by Bus in New York's First Citi Bike Fatality". The New York Times. 12 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Nanapragasam, Andrew (2014). "A public health dilemma: Urban bicycle-sharing schemes". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 105 (3): e229. doi:10.17269/cjph.105.4525. JSTOR canajpublheal.105.3.e229. PMID 25165846.

- "Are taxpayers being taken for a ride with GREENbike? | KSL.com". Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Reality check: Public bike sharing costs the public virtually nothing - Better Bike Share". Better Bike Share. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Lindsey, Joe (1 December 2016). "Do Bike Share Systems Actually Work?". Outside Online. Retrieved 5 March 2018.