Bhagat Singh Thind

Bhagat Singh Thind (October 3, 1892 – September 15, 1967) was an Indian American writer and lecturer on spirituality who served in the United States Army during World War I and was involved in a Supreme Court case over the right of Indian people to obtain United States citizenship.

Bhagat Singh Thind | |

|---|---|

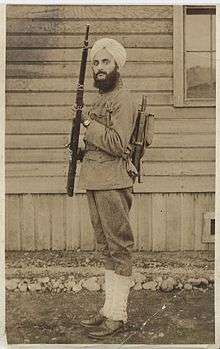

Sergeant Bhagat Singh Thind in U.S. Army uniform during World War I at Camp Lewis, Washington, in 1918. Thind, an American Sikh, was the first U.S. serviceman to be allowed for religious reasons to wear a turban as part of his military uniform. | |

| Born | October 3, 1892 |

| Died | September 15, 1967 (aged 74) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Citizenship | American |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Known for | United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind |

Thind enlisted in the United States Army a few months before the end of World War I. After the war he sought to become a naturalized citizen, following a legal ruling that Caucasians had access to such rights. In 1923, the Supreme Court ruled against him in the case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, which retroactively denied all Indian Americans the right to obtain United States citizenship for failing to meet the definition of a "white person", "person of African descent", or "alien of African nativity".[1][2]

Thind remained in the United States, earned his PhD in theology and English literature at the University of California, Berkeley, and delivered lectures on metaphysics. His lectures were based on Sikh religious philosophy, but included references to the scriptures of other world religions and the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau. He campaigned for Indian independence from the British Empire. In 1936, Thind applied successfully for United States citizenship through the State of New York.

Early life

Thind was born on October 3, 1892, in the village of Taragarh Talawa of Amritsar district in the state of Punjab in India,[3] listed as number 68 in this record. He belonged to the Thind clan of Kamboj.[4][5]

Arrival in the United States

Bhagat Singh Thind arrived in the United States in 1913 to pursue higher education at an American university. On July 22, 1918, he was recruited by the United States Army to fight in World War I, and on November 8, 1918, he was promoted to the rank of Acting Sergeant. He received an honorable discharge on December 16, 1918, with his character designated as "excellent".[6][7]

U.S. citizenship conferred many rights and privileges, but only "free white men" and "persons of African nativity or persons of African descent" could be naturalized.[8] In the United States at this time, many anthropologists used the term Caucasian as a synonym for white. Indians were also categorized as Caucasians by various anthropologists. Thus, several Indians were granted United States citizenship in different U.S. states. Thind also applied for citizenship from the State of Washington in July 1918.

First United States citizenship

Thind received his certificate of US citizenship on December 9, 1918, wearing military uniform as he was still serving in the United States Army. However, the Bureau of Naturalization did not agree with the decision of the district court to grant Thind citizenship. Thind's nationality was referred to as "Hindoo" or "Hindu" in all legal documents and in the news media despite being a practicing Sikh. At that time, Indians in the United States and Canada were called Hindus regardless of their religion. Thind's citizenship was revoked four days later, on December 13, 1918, on the grounds that Thind was not a "white man".

Second United States citizenship

Thind applied for United States citizenship again from the neighboring State of Oregon, on May 6, 1919. The same Bureau of Naturalization official who revoked Thind’s citizenship tried to convince the judge to refuse citizenship to Thind, accusing Thind of involvement in the Ghadar Party, which campaigned for Indian independence from the British Empire.[9] Judge Charles E. Wolverton wrote that Thind "stoutly denies that he was in any way connected with the alleged propaganda of the Gadar Press to violate the neutrality laws of this country, or that he was in sympathy with such a course. He frankly admits, nevertheless, that he is an advocate of the principle of India for the Indians, and would like to see India rid of British rule, but not that he favors an armed revolution for the accomplishment of this purpose." The judge took all arguments and Thind’s military record into consideration and declined to agree with the Bureau of Naturalization. Thus, Thind received United States citizenship for the second time on November 18, 1920.

Supreme Court appeal

The Bureau of Naturalization appealed against the judge’s decision to the next higher court, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which sent the case to the Supreme Court for ruling on the following two questions:

- "Is a high caste Hindu of full Indian blood, born at Amritsar, Punjab, India, a white person within the meaning of section 2169, Revised Statutes?"

- "Does the act of February 5, 1917 (39 Stat. L. 875, section 3) disqualify from naturalization as citizens those Hindus, now barred by that act, who had lawfully entered the United States prior to the passage of said act?"

Section 2169, Revised Statutes, provides that the provisions of the Naturalization Act "shall apply to aliens, being free white persons, and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent."

In preparing briefs for the Ninth Circuit Court, Thind's attorney, Sakharam Ganesh Pandit, argued that the Immigration Act of 1917 barred new immigrants from India but did not deny citizenship to Indians who, like Thind, were legally admitted before the passage of the new law. The purpose of the Immigration Act was "prospective, and not retroactive."

On February 19, 1923, Justice George Sutherland delivered the unanimous opinion of the Supreme Court to deny citizenship to Indians, stating that "a negative answer must be given to the first question, which disposes of the case and renders an answer to the second question unnecessary, and it will be so certified." The justices wrote that since the "common man's" definition of "white" did not include Indians, they could not be naturalized.[10]

Thind's citizenship was revoked and the Bureau of Naturalization issued a certificate in 1926 canceling his citizenship a second time. The Bureau of Naturalization also initiated proceedings to revoke citizenship granted to other Indian Americans. Between 1923 and 1926, the citizenship of fifty Indians was taken away.

Third and final United States citizenship

Thind received his United States citizenship through the state of New York in 1936, taking the oath for the third time to become an American citizen.

Thind had come to the United States for higher education and to "fulfill his destiny as a spiritual teacher." Long before Thind arrived in the United States, American thinkers had shown interest in Indian philosophy. Hindu scriptures translated by English missionaries were the “favorite texts” of many Transcendentalists, a society of American intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the Unitarian Church. The society flourished during the period of 1836–1860 in the Boston area and included influential members such as philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892), and writer Henry David Thoreau (1817–62).

Emerson had read Hindu religious books including the Bhagavad Gita, and his writings showed the influence of Indian philosophy. In 1836, Emerson expressed "mystical unity of nature" in his essay, "Nature." In 1868, Walt Whitman wrote the poem "Passage to India." Henry David Thoreau had considerable acquaintance with Indian philosophical works. He wrote an essay on "Resistance to Civil Government, or Civil Disobedience" in 1849 advocating nonviolent resistance against unethical laws. In 1906, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi used a similar philosophy of satyagraha, or nonviolent resistance, to gain Indian rights in South Africa. Gandhi often quoted Thoreau in his newspaper Indian Opinion.

Contributions

- Fought for United States citizenship (United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind)

- First turbaned soldier in the United States Army

- Indian independence activist and General Secretary of Ghadar Party from 1916–1917[11]

- Sikh spiritual writer and philosopher

Thind, during his early life, was influenced by the spiritual teachings of his father whose "living example left an indelible blueprint." After graduating from Khalsa College, he left for Manila, where he stayed for a year.

Thind learned about American culture from students and teachers at the University of California, Berkeley, and from working people in the lumber mills of Oregon and Washington, where he worked during summer vacations to support himself financially. His teachings incorporated the scriptures of many religions, including Sikhism. During his lectures to Christian audiences, he frequently quoted the Vedas, Guru Nanak, Kabir, and other sources in Indian philosophy. He also made reference to the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau.

Thind earned a PhD, became a writer, and was respected as a spiritual guide. He gave a new "vista of awareness" to his students throughout the United States and was able to initiate "thousands of disciples" into his expanded view of reality – "the Inner Life, and the discovery of the power of the Holy Nãm." He published many pamphlets and books, including Radiant Road to Reality, Science of Union with God, The Pearl of Greatest Price, House of Happiness, Jesus, The Christ: In the Light of Spiritual Science (Vol. I, II, III), The Enlightened Life, Tested Universal Science of Individual Meditation in Sikh Religion, and Divine Wisdom.[12]

Death

Thind was writing a book when he died on September 15, 1967. He was outlived by his wife, Vivian, whom he had married in March 1940, and his daughter Tara and son David. His son created a website[13] to propagate the philosophy for which his father devoted himself to the United States. He also posthumously published two of his father's books: Troubled Mind in a Torturing World and their Conquest and Winners and Whiners in this Whirling World.

Writings

- Radiant Road to Reality

- Science of Union with God

- The Pearl of Greatest Price

- House of Happiness

- Jesus, The Christ: In the Light of Spiritual Science (Vol. I, II, III)

- The Enlightened Life

- Tested Universal Science of Individual Meditation in Sikh Religion

- Divine Wisdom (Vol. I, II, III)

Posthumously released

- Troubled Mind in a Torturing World and their Conquest

- Winners and Whiners in this Whirling World

In media

In 2020 the story of his Supreme Court case was part of PBS’s documentary Asian Americans.[14]

References

- "United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, 261 U.S. 204 (1923)". Justia.

- "US v. BHAGAT SINGH THIND". FindLaw. FindLaw.com. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- http://pbplanning.gov.in/districts/Jandiala.pdf

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lee, Erika (2016). The Making of Asian America: A History. Simon and Schuster. p. 172. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- Rashmi Sharma Singh: Petition for citizenship filed on September 27, 1935, State of New York.

- The Multiracial Activist – www.multiracial.com – Perez v. Sharp (32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P. 2d 17)

- Doug Coulson, Race, Nation, and Refuge: The Rhetoric of Race in Asian American Citizenship Cases (Albany: SUNY Press, 2017).

- "Court Rules Hindu Not a 'White Person'; Bars High Caste Native of India From Naturalization as an American Citizen". New York Times. February 20, 1923. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dr Bhagat Singh Thind website

- Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind|Science of the Saviours

- Kristen Lopez (May 12, 2020). "'Asian Americans': PBS Documentary Compels Viewers to Honor and Remember – IndieWire". Indiewire.com. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

Lee, Erika. The Making of Asian America: A History. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2016.

Further reading

- "Hindus Too Brunette To Vote Here". The Literary Digest. March 10, 1923. p. 13. - Direct link

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bhagat Singh Thind. |