Battle of Lake Regillus

The Battle of Lake Regillus was a legendary Roman victory over the Latin League shortly after the establishment of the Roman Republic and as part of a wider Latin War. The Latins were led by an elderly Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the seventh and last King of Rome, who had been expelled in 509 BC, and his son-in-law, Octavius Mamilius, the dictator of Tusculum. The battle marked the final attempt of the Tarquins to reclaim their throne. According to legend, Castor and Pollux fought on the side of the Romans.[1]

| Battle of Lake Regillus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman-Latin wars | |||||||

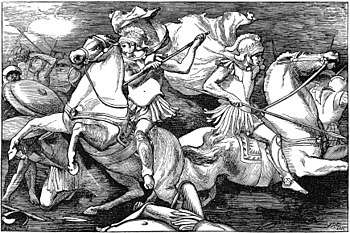

Castor and Pollux fighting at the Battle of Lake Regillus, 1880 illustration by John Reinhard Weguelin to the Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Macaulay | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Republic | Latin League | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Aulus Postumius Albus, Titus Aebutius Helva (master of the horse) |

Octavius Mamilius †, Tarquinius Superbus | ||||||

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Background

The threat of invasion by Rome's former allies in Latium led to the appointment of Aulus Postumius Albus as dictator.

The year in which the battle occurred is unclear, and has been since ancient times. Livy places the battle in 499 BC, but says some of his sources also suggest the battle occurred during Postumius' consulship in 496 BC.[2][3] The other major source for this historical period, Dionysius of Halicarnassus [4] also places the battle in 496 BC.[5] Modern authors have also suggested 493 BC[1][6] or 489 BC.[3]

Lake Regillus was located in the relic of a volcanic crater between Rome and Tusculum. The lake was drained in the fourth century BC.

According to Livy, the Volsci (a neighbouring tribe to the south of Latium) had raised troops to send to the aid of the Latins against Rome, however the haste of the Roman dictator in joining battle meant that the Volscian forces did not arrive in time.[7]

Battle

The dictator Postumius led the Roman infantry, while Titus Aebutius Helva was Master of the Horse. Tarquin was accompanied by his eldest and last remaining son, Titus. It was said that the presence of the Tarquinii caused the Romans to fight more passionately than in any previous battle.

Early in the battle, the king was injured attacking Postumius. The magister equitum charged at Mamilius, and both were wounded: Aebutius in the arm, and the Latin dictator in the chest. The magister equitum had to withdraw from the field, and direct his troops from a distance. The king's soldiers, including many exiled Romans, began to overpower the republican forces, and the Romans suffered a setback when Marcus Valerius Volusus (consul in 505 BC) was killed by a spear while attacking Titus Tarquinius, but Postumius brought fresh troops from his own bodyguard, and halted the exiles' progress.

Meanwhile, Titus Herminius Aquilinus, who had won fame fighting alongside Horatius at the Sublician bridge, and served as consul in 506 BC, engaged Mamilius and slew him; but while attempting to strip his fallen enemy and claim the spoils, Herminius was killed by a javelin. As the outcome of the battle seemed in doubt, Postumius ordered the cavalry to dismount and attack on foot, forcing the Latins to retreat and capturing the Latin camp. Tarquin and the Latin army abandoned the field, resulting in a decisive Roman victory. Postumius returned to Rome with his army, and celebrated a triumph.[8][9]

A popular legend reported that the Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, fought alongside the Romans, transfigured as two young horsemen. Postumius ordered a temple built in their honour in the Roman Forum, in the place where they had watered their horses.

In the nineteenth century, the battle was celebrated in Thomas Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome.

References

- Grant, The History of Rome, p. 37

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.19-21

- Sinnigen, William G and Boak, Arthur E R, A History of Rome to AD 565, 6th ed,1977, p. 46

- Dion. Hal. 1.66 Retrieved from http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Dionysius_of_Halicarnassus/1C*.html

- Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome, p. 216

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith, Editor

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.22

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 2.19-20

- Fasti Triumphales

Sources

- Primary sources

- Livy (1905). . Translated by Canon Roberts – via Wikisource. (print: Book 1 as The Rise of Rome, Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-282296-9)

- Secondary sources

- Grant, Michael (1993). The History of Rome. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-11461-X.

- Livy: Ab urbe condita Book II cap. 19; 20.

- Ab Urbe Condita (Latin)

- The Battle of Lake Regillus poem from Macaulay's "Lays of Ancient Rome".

- Cornell, Tim, The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars, C.1000-263 BC, Routledge, 1995. ISBN 0-415-01596-0.

- Drago, Massimo, The battle of Lake Regillus, Ancient Warfare magazine, 2013. ISSN 2211-5129.