Bathing Venus

The Bathing Venus is a bronze sculpture attributed to Giambologna (1529-1608), the leading late Renaissance sculptor in Europe. It was most likely created for King Henry IV of France with other bronzes as a diplomatic gift from Ferdinando I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, to embellish the gardens of the Royal castle in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. A Mercury in the Louvre, recently attributed to Hans Reichle[1] and Giambologna's Triton in the Metropolitan Museum of Art were likely to have been also part of this grand-ducal gift. Documents relating to the commission have recently been discovered in the Florentine State Archives.[2]

To enhance the erotic attraction of the female nude, the artist has contrived that the goddess hides her face behind her raised arm holding up a vessel, with which she is bathing. With the other hand she dries herself with a handkerchief. The beholder can approach her without entering her line of sight and when he is in front of her there is a moment of reciprocal discovery. The seated statue is a second remodelled and rethought version of a marble Venus by the same artist, today in the J. Paul Getty Museum. The two versions show so many similarities that they must derive from a common starting point – most likely a full-scale model, a „modello in grande“. It is documented that Giambologna followed the practice of making full-scale models and keeping them in his workshop.

The bronze Venus was rediscovered in the late 1980s in the possessions of a scrap-metal dealer near Paris, who seems to have obtained it from the demolition of the Château of Chantemesle (Corbeil-Essonnes) in the early 1960s. It was at first dismissed as a later copy after the Getty Venus,[3] but recent research has argued its autograph authorship by Giambologna.[4]

Attribution

The attribution to Giambologna is based on the style of the figure. The artist had one style for marble works and a rather different one applied for works in bronze. The bronze Venus shows stylistic features that cannot be found on the Getty marble but do appear on many other large bronzes in Giambologna's oeuvre. This can be fully demonstrated by an exhaustive comparison of particular details and mannerisms in Giambologna's work as a whole. The garment of the bronze Bathing Venus was left unfinished in parts on purpose, in order to create variety and contrasts of texture. Use of ‘unfinished’ (non-finito) passages is a stylistic device that Giambologna adopted from Donatello and which he used for his bronze sculptures throughout his career. Its crucial importance for the understanding of Giambologna's style has recently been shown by the art expert A. Rudigier.[5] The base shows French ornament of the period of Henri IV. Its appearance on a figure made by the Florentine court sculptor is explained by its destination as a diplomatic gift to the king of France. TL-dating of the core material has shown with a probability of 99.7% that the casting of the bronze took place before 1648. Tests were carried out by the Rathgen Research Laboratory of the Berlin State Museums (1996), commissioned by the J. Paul Getty Museum, confirmed by Oxford Authentication, Wantage (2008), and re-checked by Professor Ernst Pernicka at the Curt-Engelhorn-Center for Archaeometry in Mannheim (2013).

The Founder's Signature

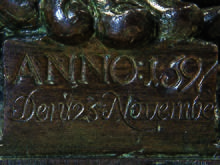

Following an old established tradition in European works of metal, the bronze Venus is signed by its founder, Gerhard Meyer: “ME FECIT GERHARDT MEYER HOLMIAE“ (“Gerhardt Meyer made me in Stockholm“). On the small block upon which the right foot of the bronze Venus rests, one can also read the exact day of casting: ANNO 1597 / Den 25 Novembe[r] (“In the Year 1597 on 25 November“). The founder's signature is a sign of recognition of the very great skill required in casting a large bronze. Gerhardt Meyer was a member of a well-known dynasty of founders, working around the Baltic Sea in Riga, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Helsingör between the late 16th and the late 18th century. Several generations of the family bore the Christian name Gerhardt and they all signed with the same traditional formula: ME FECIT GERHARDT MEYER.

The Latin wording of the founder's signature on the bronze Venus contains an obvious mistake by apparently stating that the statue was created in Stockholm. In 1597 the statue cannot have been made in Stockholm (Latin: Holmia), as its casting model could only have been in Florence. The formula of the signature must be considered like a present-day marque, as confirmed by A. Zaijc (Austrian Academy of Science) and Charles Avery, which the craftsman punched routinely with a pre-existing set of punches. Craftsmen and artists were usually ignorant of Latin, and in this case this is demonstrated by Meyer giving the casting date in his mother tongue German instead of in Latin. The formula was used later even in cases where the indication of HOLMIAE (Latin for “at Stockholm”) should have been replaced with HOLMIĀ (or HOLMIENSIS), referring to the origin of the caster. The same error occurs in the signatures of Giambologna and of one of his foremost pupils, Pietro Francavilla, when they want to state their Flemish origin (Latin: BELGĀ), but erroneously indicate that the figures in question have been made ‘in Belgium’ (Latin: BELGIAE) instead of their real place of manufacture, Florence. Founders were one of the most itinerant professions at the time. Meyer is documented in Stockholm 1592-95 and must be identical with a “Gerardo fiamingho” who appears in Florence in February 1598.[6]

The discussion about the “5”

Of the indication of the year three numbers, 1, 7, and 9, are punched whereas the 5 is engraved. The reason for this is a casting fault underneath, a so-called Lunker, which made the material so thin in this spot that punching in a letter would have created a hole. This Lunker one can see with the naked eye and has been further proved in the year 2012 by a computer-tomography made by the Fraunhofer Institut (Fürth). In 1996 the renowned art historian Gino Corti wrote: “It is really ANNO 1597, and in the next line it is: 25 Novembe, even if the two 5s are a bit different: for me there is no doubt.”[7]

Up to the 18th century there existed two equivalent forms of the number 5: one with and one without stroke on the top. The use of two different forms of the same number or letter is no rarity in old inscriptions.

The German art-historian Dorothea Diemer has claimed since 1999 that the indication of the year in the founder's signature 1597 should be read as “1697”. She considers the bronze Venus a Swedish aftercast of the marble Venus, executed by the later Gerhardt Meyer IV (1667-1710).[8] The first publication of the bronze Venus, in the Catalogue of Italian Sculpture in the J. Paul Getty Museum, was based on her opinion, even though it had already at the time been contradicted by the technical data made available by the Getty Research Institute. In 2018 Diemer together with Linda Hinners repeated her claim in an article in the Burlington Magazine (2018).[9]

The theory of 1697

The marble Venus today in the J. Paul Getty Museum was a Medici gift to the Bavarian court made before 1584. In 1632 it was brought as booty from the Thirty Years' War from Munich to Sweden. In 1688 it was recognized as a work of Giambologna by Nicodemus Tessin the Younger. Around 1700 a number of simplified aftercasts of the marble were made in metal and plaster, of which six are known today. One is in Fredensborg Castle, Denmark, and the others in Ericsberg Castle, Sweden. Around 1700 a later member of the Meyer family of founders, known through a number of documents, was active in Stockholm. He had been sent by the King of Sweden to Paris as an apprentice to the most famous founder of the time, Jean-Balthazar Keller, in order to learn the technique of figure casting.

Diemer's hypothesis is based on her interpretation of the 5, which she believes to be a 6. From an epigraphic point of view, however, the indication of the year shows a 5. It is indispensable that a 6 would be closed in its lower part on the left hand side. Since this is not case she claims that the number 5 should be an unsuccessful 6. The technical explanation she has given of the way this might have happened has been disproved by A. Rudigier in a reply to her article in The Burlington Magazine.[10]

The claim that the bronze Venus is an aftercast of the Getty-marble has also been disproved. Peggy Fogelman already observed: “A comparison of measurements reveals that some dimensions of the marble original are actually smaller than those of the bronze copy, while others are larger. This inconsistent relationship between measurements of the sculptures suggests that the bronze was not cast from moulds of the marble.“[11] Moreover, the surface of the bronze reproduces traces of a clay model, which could not happen if it were an aftercast. The quality of the bronze makes it impossible to put it into the same group as the known Swedish aftercasts of around 1700. The Henri IV ornament on the base had a revival in the court art of Louis XIV. Diemer argues that the ornament dates from that later period (without giving stylistic arguments).

The bronze Venus has markedly varied surface textures, clearly differentiating hair, body and cloth in a naturalistic way – typical features of late Renaissance bronze art in Florence, but by 1700 completely out of fashion in Baroque bronze sculpture. Diemer has no explanation why the artist who modelled the bronze Venus, if he were active in Stockholm around 1700, would produce a very expensive bronze work with features entirely out of fashion at the time. In particular she has no explanation how such a hypothetical artist should have been able to match Giambologna's bronze style, as it could not be deduced from the marble, down to the smallest detail. It is also documented that Keller, the master of Gerhardt Meyer IV stated that his training had been so incomplete that he had not learnt how to cast monumental figures. Finally, the theory of a manufacture date in 1697 is contradicted by results of technical analysis.

Exhibition

The bronze Venus has been included in the exhibition “Plasmato del Fuoco. The bronze sculpture in the Florence of the last Medici“ (Florence, Palazzo Pitti, 18 September 2019 until 12 January 2020) as an autograph work by Giambologna. In the catalogue entry the director of the Uffizi and curator of the exhibition, Eike D. Schmidt calls the bronze Bathing Venus a masterpiece of 16th c. Italian art.[12] In his entry in the catalogue regarding the argument over the attribution between Diemer and Rudigier in the Burlington Magazine[13] he considers Diemer's hypothesis as entirely disproved. This view is shared by the scholars Charles Avery, Bertrand Jestaz and Lars-Olof Larsson, who have all given written statements. All three scholars had participated in the groundbreaking Giambologna exhibition in 1978 (Edinburgh, London, Vienna). The inclusion of the sculpture in this exhibition has provoked a bitter media polemic initiated by an article in the New York Times from November 2019 titled “Is it a ‘5’ or a ‘6’?[14] The answer could make an art fortune“. In the article Diemer accused Eike D. Schmidt to have significantly increased the market value of the piece by exhibiting it in the Pitti show. In response the Uffizi issued a press release on 27 November 2019.[12] On 13 December 2019 the New York Times was criticized for having misrepresented the case by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.[15]

Sources

- Rudigier, Alexander, «Les bronzes envoyés de Florence à Saint-Germain-en-Laye, la Vénus de 1597 et les dernièrs oeuvres de Jean Bologne», in: Bulletin monumental 174, 3 (2016), 287-356. This attribution was discussed by Geneviève Bresc-Bautier,, «À propos de Jean Bologne et les jardins d' Henri IV. Observations», in: Bulletin monumental 176, 4 (2018), 321-322 and Rudigier, Alexander, «À propos de Jean Bologne et les jardins d' Henri IV. Réponse [aux observations de Geneviève Bresc-Bautier]», in: Bulletin monumental 176, 4 (2018), 321-324.

- By B. Truyols. See: A. Rudigier, B. Truyols: “Giambologna. Court Sculptor to Ferdinando I. His art, his style and the Medici gifts to Henri IV“ (2019), pp. 311-366.

- P. Fogelman, P. Fusco and M. Cambarari, eds.: Italian and Spanish Sculpture. Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection, Los Angeles 2002

- A. Rudigier, B. Truyols: “Giambologna. Court Sculptor to Ferdinando I. His art, his style and the Medici gifts to Henri IV“ (2019)

- Rudigier/Truyols, Giambologna,pp. 246ff.

- In Florentine documents of this period notices of people frequently omit surnames. This was particularly the case with foreign craftsmen and artists. For example, Adriaen de Vries and Hans Reichle are referred to simply as ‘Adriano fiammingho’ and ‘Ansi Tedesco’ respectively.

- Rudigier/Truyols, Giambologna, P. 289, note 4.

- Cf. Fogelman, Peggy, «Giambologna (Giovanni Bologna). Female Figure», in: Italian and Spanish Sculpture. Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection, Peggy Fogelman/Peter Fusco/Marietta Cambarari (Hg.), Los Angeles 2002, p. 96, note 29.

- Diemer, Dorothea/Hinners, Linda, «"Gerhardt Meyer made me in Stockholm": a bronze "Bathing Woman" after Giambologna», in: The Burlington Magazine 160, 1384 (2018), 545-553.

- Rudigier, Alexander, «"Letter to the editor" [Response to Diemer, Dorothea/Hinners, Linda, «"Gerhardt Meyer made me in Stockholm": a bronze "Bathing Woman" after Giambologna», in: The Burlington Magazine 160, 1384 (2018), 545-553]», in: The Burlington Magazine 160 (2018), 813-815.

- Fogelman, Peggy, «Giambologna (Giovanni Bologna). Female Figure», in: Italian and Spanish Sculpture. Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection, Peggy Fogelman/Peter Fusco/Marietta Cambarari (Hg.), Los Angeles 2002, p. 90.

- "Firenze, scoppia il caso Venere del Giambologna: NY Times solleva dubbi contro gli Uffizi, che si difendono". www.finestresullarte.info.

- Plasmato dal Fuoco. La scultura in bronzo nella Firenze degli ultimi Medici, Eike D. Schmidt/Sandro Bellesi/Riccardo Gennaioli (Bearb.), Livorno 2019 (AK Florenz, Palazzo Pitti-Tesoro dei Granduchi, 18.9.2019-12.1.2020), p. 140.

- G. Bowley: "Is it a '5' or a '6'? The answer could make an art fortune", article from the New York Times:

- Trinks, Stefan. "Bronzeskulpturen in Florenz: Der Stolz des Gießers" – via www.faz.net.

Literature

P. Fogelman, P. Fusco and M. Cambarari, eds.: Italian and Spanish Sculpture. Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection, Los Angeles 2002,

A. Rudigier, B. Truyols, with a foreword by B. Jestaz: “Jean Bologne et les jardins d’Henri IV“, Bulletin monumental 174, 3 (2016), pp. 247–373.

D. Diemer and L. Hinners: “Gerhardt Meyer made me in Stockholm”: a bronze “Bathing woman” after Giambologna’, The Burlington Magazine 160 (2018), pp. 545–53.

A. Rudigier, B. Truyols: “Giambologna. Court Sculptor to Ferdinando I. His art, his style and the Medici gifts to Henri IV“ (2019) pp. 44–129.