Barbara Strozzi

Barbara Strozzi (also called Barbara Valle; baptised 6 August 1619 – 11 November 1677) was an Italian singer and composer of the Baroque Period. During her lifetime, Strozzi published eight volumes of her own music, having more music in print than any other composer of the era.[1] This was made possible without any support from the Church or consistent patronage of the nobility.

Strozzi's life and career has been overshadowed by the claims of her being a courtesan, which cannot be completely confirmed as at the time female music making was often assumed to be an intellectual asset of a courtesan.

Biography

Early life and adolescence

Barbara Strozzi (at birth, Barbara Valle) was born in Venice in 1619 to a woman known as “La Greghetta” (in other sources she is also referred to as Isabella Griega or Isabella Garzoni). She was baptised in the church of Santa Sofia in the Cannaregio district (sestiere) of Venice. Although Barbara's birth certificate does not provide information on her father's identity, it is assumed that her biological father may have been Giulio Strozzi, a poet and libretist,[2] a very influential figure in 17th - century Venice. Giulio Strozzi was a member of the Incogniti, one of the largest and most prestigious intellectual academies in Europe and a major political and social force in the Republic of Venice and beyond.[1] Not too much is known about Barbara's mother, but historians think that Isabella was a servant of Giulio, as both Barbara and Isabella lived in Giulio's household and were listed in his will. Although Barbara was an illegitimate child (her parents were not married at the time of her conception or birth), her father Giulio referred to her as his “adoptive daughter” and played an instrumental role in helping her establish her career as a musician later in her life.

Little is known about Barbara's childhood; more detailed accounts of her life concern the end of her childhood and early adolescence. At the time, Venice had suffered plagues which had killed much of its population. However, Barbara who had survived along with her mother had reached the age of 12 by the first Festa della Salute in 1631. By this time, Barbara had already begun to develop as a musician and started to demonstrate virtuosic vocal talent along with being able to accompany herself on the lute or theorbo. In her book, “Sounds and Sweet Airs”, historian Anna Beer states that Barbara Strozzi's musical gifts, (especially her captivating singing voice) became more evident at the time of her early adolescence and this led to Giulio arranging lessons in composition for Strozzi with one of the leading composers at the time, Francesco Cavalli. These lessons proved to be fruitful: at the age of fifteen, Barbara is described as “la virtuosissima cantatrice di Giulio Strozzi”, Giulio Strozzi's virtuosic singer.[1] Around Barbara's sixteenth birthday, Giulio actively started to publicise Barbara's musical talents, ensuring dedications of works for her. Giulio subsequently established Accademia degli Unisoni, a subsidiary of the Incogniti, which also welcomed musicians into the privileged social circle. Unisoni , operating from the Strozzi household, became the major performance space for young Barbara, ensuring her opportunities of performing as a singer, as well as semi-public performances of her own works. On 1637, being 18 years old, Barbara took her father's last name Strozzi, keeping it until her death.

Life as a young musician

By her late teens, Barbara had started to gain a reputation for her singing. In 1635 and 1636, two volumes of songs were published by Nicole Fontei, called the Bizzarrie poetiche (Poetic Oddities), full of praise for Barbara's singing ability.[3] The performance experience Barbara had at Unisoni equipped her with the vocal expertise that also manifested itself in her later publications, signifying her compositional talent.

In 1644 her first volume of works Il primo libro de’madrigali (“First Book of Madrigals”) appeared in print. At this time the young musician is yet to have the confidence and self - worthiness of her later years. This reflects on the preface of the work, where she states: "Being a woman I am concerned about publishing this work. Would that it lie safely under a golden oak tree and not be endangered by swords of slander which have already been drawn to battle against it."

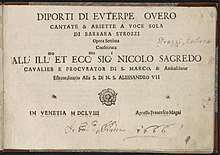

As a young musician, Barbara sought out patronage that was not always successful. Her opus 2, Dedicated to Ferdinand III of Austria and Eleanora of Mantua on the occasion on the marriage went unnoticed. Other notable dedicatees include Anne de'Medici, the Archduchess of Austria, Nicolò Sagredo, later Doge of Venice for whom she dedicated her opus 7, and Sophia, Duchess of Brunswick and Lüneburg. She is also assumed to have composed several songs for Duke of Mantua in 1665, a year after her last known published works.[4]

Later life and death

Little is known of Strozzi's life during the 1640s, however it is assumed that Strozzi was the concubine of a Venetian nobleman Giovanni Paolo Vidman. This relationship led Barbara to become a mother of four.

During this time there were financial dealings between her and Vidman. It is believed that Barbara gave out a loan that would have to be repaid after Vidman's death. The near 10% interest might have been a way of ensuring some support for Barbara and her children after Vidman's death.

Strozzi died in Padua in 1677 aged 58. She is believed to have been buried at Eremitani.[5] When she died without leaving a will, her son Giulio Pietro claimed her inheritance in full.[6]

Personal life

Although Strozzi never married, she had four children; her two daughters joined a convent, and one of her sons became a monk.[7] In a letter, written after Barbara's death, it is reported laconically that she “was raped by Count Vidman, a Venetian nobleman. She had a son who also bears the name "Giulio Strozzi”. Vidman was a patron of the arts. Whether Vidman raped her or not, Strozzi certainly did not marry him since Vidman was already married. Regardless, Vidman certainly was the father of baby Giulio, and then two further children, Isabella in 1642 and Laura in 1644, and possibly a fourth, Massimo. It has also been suggested that the rape claim might merely have been a story circulated in order to protect Barbara's reputation.

Compositions

Strozzi was said to be "the most prolific composer – man or woman – of printed secular vocal music in Venice in the middle of the [17th] century."[8] Her output is also unique in that it only contains secular vocal music, with the exception of one volume of sacred songs.[9] She was renowned for her poetic ability as well as her compositional talent. Her lyrics were often poetic and well-articulated.[10]

Nearly three-quarters of her printed works were written for soprano, but she also published works for other voices.[11] Her compositions are firmly rooted in the seconda pratica tradition. Strozzi's music evokes the spirit of Cavalli, heir of Monteverdi. However, her style is more lyrical, and more dependent on sheer vocal sound.[12] Many of the texts for her early pieces were written by her father Giulio. Later texts were written by her father's colleagues, and for many compositions she may have written her own texts. There are seven printed volumes of her compositions which have survived. Likewise, much more of Strozzi's unpublished works are currently in collections in Italy, Germany, and England in manuscript form. Her music's irregular barring has been modernized to accommodate modern performances. Like many of her contemporary composers, Strozzi mostly utilized texts from the poet Marino. These Marinist texts would serve as a vehicle for Strozzi to express herself as well as to challenge the gender roles of her time. Il primo libro di madrigali, per 2–5 voci e basso continuo, op. 1 (1644) was dedicated to Vittoria della Rovere, thriller Venetian born Grand Duchess of Tuscany. The text is a poem by Giulio Strozzi. Strozzi published one work of known religious pieces. Her opus 5 written in 1655 was dedicated to the Arch-Duchess of Innsbruck, Anna de Medici. Her motet “Mater Anna” paid homage not only to the Catholic saint/mother of the virgin Mary but also to the arch-duchess. Strozzi was highly sensitive to the subliminal meaning in her texts and much like Arcangela Tarabonti the text carried much underlying issues regarding gender.

Publications

- Il primo libro di madrigali, per 2–5 voci e basso continuo, op. 1 (1644)

- Cantate, ariette e duetti, per 2 voci e basso continuo, op. 2 (1651)

- Cantate e ariette, per 1–3 voci e basso continuo, op. 3 (1654)

- Sacri musicali affetti, libro I, op. 5 (1655)

- Quis dabit mihi, mottetto per 3 voci (1656)

- Ariette a voce sola, op. 6 (1657)

- Diporti di Euterpe ovvero Cantate e ariette a voce sola, op. 7 (1659)

- Arie a voce sola, op. 8 (1664)

Recordings and performances

Recordings

There are numerous recordings. Some of them contained Barbara's works exclusively, others only indexed few pieces.

- Barbara Strozzi: La Virtuosissima Cantatrice (2011)[13]

- Barbara Strozzi: Ariette a voce sola, Op. 6 / Miroku, Rambaldi (2011)[14]

- Barbara Strozzi: Passioni, Vizi & Virtu / Belanger, Consort Baroque Laurentia (2014)[15]

- Barbara Strozzi: Opera Ottava, Arie & Cantate (2014)[16]

- Barbara Strozzi: Lagrime Mie (2015)[17]

- Due Alme Innamorate - Strozzi,Etc / Ensemble Kairos (2006)[18]

- A Golden Treasury Of Renaissance Music (2011)[19]

- Lamenti Barocchi Vol 3 / Vartolo, Capella Musicale Di San Petronio (2011)[20]

- Ferveur & Extase / Stephanie D'oustrac, Amarillis (2012)[21]

- La Bella Piu Bella: Songs from Early Baroque Italy (2014)[22]

- Dialoghi A Voce Sola (2015)[23]

- O Magnum Mysterium: Italian Baroque Vocal Music (2015)[24]

Performances

With the thrive of historical performance movement, an increasing amount of performances which dedicated with Barbara's works were put on stage within the past few years.

Some of them could be found on YouTube and other platforms.

- Chamber Music Foundation of New England, Music of Claudio Monteverdi & Barbara Strozzi (2017)[25]

- Early Music America's 2018 Emerging Artists Showcase during the Bloomington Early Music Festival.(2018)[26]

- Old First Concerts, Ensemble Draca performs Amante Fedele, August 12, 2018.(2018)[27]

- WWFM radio broadcast, Brooklyn Baroque Presents Barbara Strozzi and Her World (2018)[28]

Citations

- Beer, Anna (2017). Sounds And Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women Of Classical Music. London: OneWorld. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-78607-067-8.

- "Giulio Strozzi". Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- Beer, Anna. Sounds and Sweet Airs.

- Rosand, Ellen; Glixon, Beth L. (2001). "Barbara Strozzi". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.26987.

- Glixon 1999.

- Glixon 1999, p. 141.

- Cypess, Anna. "Barbara Strozzi, Italian Singer and Composer". Britannica. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Glixon 1999, p. 135.

- Heller 2006.

- Glixon 1999, p. 138.

- Kendrick 2002.

- Rosand 1986, p. 170.

- "Barbara Strozzi: La Virtuosissima Cantatrice - Saydisc: SAR061 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Barbara Strozzi: Ariette a voce sola, Op. 6 / Miro ... - Tactus: TC616901 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Barbara Strozzi: Passioni, Vizi & Virtu / Belanger ... - Stradivarius: STR33948 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Barbara Strozzi: Opera Ottava, Arie & Cantate - Glossa: GCDC81503 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Barbara Strozzi: Lagrime Mie - Querstand: VKJK 1303 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Due Alme Innamorate - Strozzi,Etc / Ensemble Kairo ... - Urtext: UMA2020 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "A Golden Treasury Of Renaissance Music - Saydisc: SAR065 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Lamenti Barocchi Vol 3 / Vartolo, Capella Musical ... - Naxos: 8503241 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Ferveur & Extase / Stephanie D'oustrac, Amarillis - Ambronay: AMY027 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "La Bella Piu Bella: Songs from Early Baroque Italy - Glossa: GCD922902 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Dialoghi A Voce Sola - Raum Klang: RK3306 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "O Magnum Mysterium: Italian Baroque Vocal Music - Bergen Digital: 28907589 | Buy from ArkivMusic". www.arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Music of Claudio Monteverdi & Barbara Strozzi, retrieved 29 September 2019

- Adriana Ruiz, soprano - Songs of Barbara Strozzi - EMA's 2018 Emerging Artists Showcase, retrieved 29 September 2019

- Ensemble Draca performs Amante fedele (Non pavento io) by Barbara Strozzi, retrieved 29 September 2019

- Brooklyn Baroque Presents Barbara Strozzi and Her World, retrieved 29 September 2019

Sources

- Beer, Anna (2016). Sounds and Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women of Classical Music. London: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-856-6.</ref>

- Glixon, Beth L. (1997). "New light on the life and career of Barbara Strozzi". The Musical Quarterly. 81 (2): 311–335. doi:10.1093/mq/81.2.311.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glixon, Beth L. (1999). "More on the life and death of Barbara Strozzi". The Musical Quarterly. 83 (1): 134–141. doi:10.1093/mq/83.1.134.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heller, Wendy (2006). "Usurping the place of the muses: Barbara Strozzi and the female composer in seventeenth-century Italy". In Stauffer, George B. (ed.). The World of Baroque Music: New Perspectives. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 145–168. ISBN 978-025334798-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kendrick, Robert (2002). "Intent and intertextuality in Barbara Strozzi's sacred music". Recercare. Rivista per lo Studio e la Practica della Musica Antica. 14: 65–98. JSTOR 41701379.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosand, Ellen (1986). "The voice of Barbara Strozzi". In Bowers, Jane; Tick, Judith (eds.). Women Making Music: the Western art tradition, 1150-1950. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 168–190. ISBN 978-025201204-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schulenberg, David (2001). Music of the Baroque. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512232-1.</ref>

Further reading

- Ellen Rosand with Beth L. Glixon. "Barbara Strozzi", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (grovemusic.com (subscription required).

- Magner, Candace A. (2002). "Barbara Strozzi: a documentary perspective", The Journal of Singing, 58/5.

- Mardinly, Susan J. (2002). "Barbara Strozzi: from madrigal to cantata", Journal of Singing, 58 (5) 375–391.

- Mardinly, Susan J. (2009). "A View of Barbara Strozzi", International Alliance for Women in Music Journal, 15 (2).

- Mardinly, Susan (2004). "Barbara Strozzi and the pleasures of Euterpe", PhD Diss., University of Connecticut, 2004.

- Rosand, Ellen (1978). "Barbara Strozzi, virtuosissima cantatrice: the composer’s voice", Journal of the American Musicological Society, 31, (2) 241–281.

- Schulenberg, David (2001). "Barbara Strozzi" Music of the Baroque, Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 110–115.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barbara Strozzi. |

- Barbara Strozzi at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Free scores by Barbara Strozzi at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Barbara Strozzi in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Biography, discography, bibliography, and complete list of her works

- Recordings and Works List of Barbara at the ArkivMusic