Bakassi conflict

The Bakassi conflict is an ongoing insurgency which started in 2006, in the Bakassi Peninsula of Cameroon waged by local separatists against Cameroonian government forces. After the independence of both Cameroon and Nigeria the border between them was not settled and there were other disputes. The Nigerian government claimed the border was that prior to the British–German agreements in 1913. On the other hand, Cameroon claimed the border laid down by the British–German agreements. The border dispute worsened in the 1980s and 1990s after some border incidents occurred, which almost caused a war between the two countries.

| Bakassi conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the conflict in the Niger Delta and the piracy in the Gulf of Guinea | |||||||

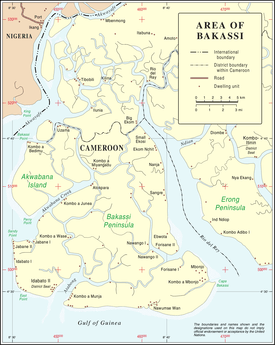

The Bakassi Peninsula in the Bight of Bonny | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

BFF MEND SCAPO LSCP BSDF | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Unknown | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

50 killed (2008) 1,700 internally displaced | |||||||

Location of the Bakassi Peninsula in Africa | |||||||

In 1994 Cameroon went to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to avoid war with Nigeria after many armed clashes occurred in the disputed regions. Eight years later the ICJ ruled in Cameroon's favour and confirmed the 1913 border made by the British and Germans as the international border between the two countries. Nigeria confirmed it would transfer Bakassi to Cameroon.

In June 2006 Nigeria signed the Greentree Agreement, which marked the formal transfer of authority in the region, and the Nigerian Army partly withdrew from Bakassi. The move was opposed by many Bakassians who considered themselves Nigerians and they started to arm themselves on 2 July 2006. Two years later the Nigerian Army fully withdrew from the peninsula and it transitioned to Cameroonian control. More than 50 people were killed between the start of the conflict and the full withdrawal of the Nigerians. The conflict largely ended on 25 September 2009 with an amnesty deal. Only the group, the Bakassi Freedom Fighters (BFF) and militants from the Niger Delta continue to fight. Since then sporadic clashes have occurred in Bakassi.

Background

Early years of disputes

After the independence of both Nigeria and Cameroon in 1960,[1][2] the status of British Cameroons was unclear. A United Nations-sponsored and supervised plebiscite took place the following February resulting in the northern part of the territory voting to remain part of Nigeria, while the southern part voted for reunification with Cameroon.[1] The northern part of British Cameroons was transferred to Nigeria the following June, while the southern part joined Cameroon in October.[3] However, the land and maritime boundaries between Nigeria and Cameroon were not clearly demarcated. One of the resultant disputes was in the Bakassi Peninsula, an area with large oil and gas reserves,[4] which had been de facto administered by Nigeria.[5] In the early 1960s, Nigeria recognised that the peninsula was not a historical part of Nigeria.[2] Nigeria claimed that the British had made an agreement with the local chiefs for protection, and that the resultant border of 1884 should be the official border. Cameroon claimed that the British–German border agreements in 1913 should demarcate the border between the two countries.[6][7] The dispute was not a major issue between the two countries until the Nigerian President, Yakubu Gowon, was overthrown by General Murtala Mohammed in July 1975. Mohammed claimed that Gowon had agreed to transfer Bakassi to Cameroon when he signed the Maroua Declaration in June. Mohammed's government never ratified the agreement, while Cameroon regarded it as being in force.[8]

Border conflict

In the 1980s tensions rose at the border; with the two countries nearly going to war on 16 May 1981, when five Nigerian soldiers were killed during border clashes. Nigeria claimed that Cameroonian soldiers fired first on the Nigerian patrol. Cameroon claimed Nigerian soldiers opened fire against a Cameroonian vessel close to Bakassi[9] and that Nigeria violated international law in Cameroon's territory.[9][10] There were two further armed incidents in February 1987 in the Lake Chad region; three Cameroonians were kidnapped and tortured by the Nigerians.[11] That same year Cameroonian gendarmes attacked 16 villages around Lake Chad and exchanged the Cameroonian flag for the Nigerian flag.[10] Another incident occurred on 13 May 1989 when Nigerian soldiers boarded and inspected a Cameroonian fishing boat close to Lake Chad.[12] In April 1990 Nigerian soldiers kidnapped and tortured two people. A couple of months later Nigeria claimed that Cameroon was annexing nine fishing settlements on the peninsula.[13] Between April 1990 and April 1991 Nigerian soldiers made a number of incursions into the town of Jabane; on one occasion replacing the Cameroonian flag with the Nigerian standard. The following July the Nigerians occupied the town of Kontcha. The Nigerian Army made veiled threats that it would occupy some areas around Lake Chad.[14] A 1992–1993 Cameroonian attack in Lake Chad resulted in the oppression of Nigerians, some of whom were killed and the rest subject to discriminatory taxation.[10] Despite years of negotiations between the two countries, their relations became worse after Nigerian soldiers occupied Jabane and Diamond Island in the Bakassi Peninsula on 17 November 1993.[13]

Soon thereafter Nigeria accused the Cameroonian Army of having launched incursions into Bakassi and in response sent 500–1,000 soldiers to protect its citizens on the peninsula in December.[13] Tensions rose when both Nigeria and Cameroon sent additional forces to Bakassi on 21 December.[15] The following January the Cameroonians killed an unknown number of Nigerian citizens. On 17 February 1994, the Nigeria-occupied territory close to Lake Chad received 3,000 refugees from the village of Karena after they fled from a violent crackdown by the Cameroonians. During the crackdown 55 people were burnt alive; 90 others were wounded and parts of the village were torched as well. Soon after another incident was reported close to the Cameroon–Nigeria frontier; Cameroonian gendarmes attacked the village of Abana in Cross River State over the border, killing 6 people and sinking 14 fishing boats.[16] On 18–19 February, Nigerian forces attacked the Cameroonians and occupied now the full peninsula including the villages of Akwa,[17] Archibong, Atabong, and Kawa Bana.[18] Between 1–25 people were killed in the clashes.[19] On 29 March, Cameroon referred the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ).[20] In early August 1995 heavy fighting took place, and local sources claim that 30 people were killed; this was never officially confirmed.[21] On 3 February 1996, another clash occurred, resulting in several casualties.[22] After these armed incidents, Nigeria alleged that France had deployed soldiers in the region. France stated that it had stationed two helicopters and fifteen paratroopers in Cameroon, but had not deployed to the peninsula. Between late 1999 and early 2000 French forces established a military base close to the disputed territory. The fighting between 1995 to 2005 is believed to have claimed 70 lives.[13]

Prelude

In 2001, the Cameroonian Army suffered two killed and eleven missing in what was described at the time as a pirate attack.[23] On 10 October 2002, the ICJ determined that Cameroon was the rightful owner of the peninsula.[24] In Bakassi, there were at least 300,000 Nigerians, at the time they made up 90 per cent of the population. They had to choose between giving up their Nigerian nationality; keeping it and being treated as foreign nationals;[23] or leaving the peninsula and moving to Nigeria.[13] The United Nations (UN) supported the ICJ verdict, putting pressure on Nigeria to accept it.[25] The Nigerian President, Olusegun Obasanjo, had attracted a lot of criticism from the international community and from within Nigeria.[26] He grudgingly accepted the judgement, although he did not immediately withdraw the Nigerian forces from the peninsula.[26][27]

On 12 June 2006, Nigeria and Cameroon signed the Greentree Agreement, allowing Nigeria to keep its civil administration in Bakassi for another two years. The Nigerian Army agreed to withdraw at least 3,000 soldiers[4] within 60 days.[13] it also agreed to give back a part to Cameroon.[28] Following the agreement, a Bakassian delegation threatened to declare independence if the handover was carried out.[27] On 2 July 2006 the Bakassi Movement for Self-Determination (BAMOSD) announced that it would join the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) to secede from Cameroon and on the 9th, they carried out the threat. They and the Southern Cameroons People's Organisation (SCAPO) declared the independence of the "Democratic Republic of Bakassi".[29] The separatists were supported by Biafran separatist rebels.[30] Nigeria's Senate claimed in November 2007 that ceding Bakassi was illegal, but this action by the senate had no effect.[26]

Main phase of the conflict

René Claude Meka, the Cameroon Chief of Staff, was tasked with securing the territory by deploying the Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR).[31] The insurgency was largely sea-based and the mangroves of Bakassi offered the insurgents hiding places. They used pirate tactics in their struggle: attacking ships, kidnapping sailors and carrying out seaborne raids on targets as far away as Limbe and Douala.[32] Nigeria also faced insurgent attacks, as rebels in the southern part of the country were fiercely opposed to the border change.[33] On 17 August 2006 the leader of BAMOSD died in a car accident together with 20 others in Cross River State.[34]

Clashes occurred in the region between suspected Nigerian soldiers and Cameroon soldiers on 13 November 2007, in which 21 Cameroonian soldiers died. Nigeria denied involvement in the clashes and claimed its soldiers were also attacked by an unknown armed group; it also claimed none of its soldiers were killed. The region was beset by both Nigerian criminals and rebels;[35] and a previously unknown rebel group called the Liberators of the Southern Cameroon claimed responsibility for some killings.[36] More Cameroon soldiers were killed in attacks in June and July 2008.[33] On 14 August, Nigeria officially withdrew from Bakassi, with 50 people having been killed in the previous year.[28] In October 2008 a militant group known as the Bakassi Freedom Fighters (BFF) boarded a ship and took its crew hostage, threatening to execute them unless the Cameroon government agreed to negotiate on Bakassian independence.[33] This BFF action failed to impact the policies of Nigeria and Cameroon regarding the peninsula. On 14 August 2009 Cameroon assumed complete control of Bakassi.[33] On 25 September an amnesty offer was made and most Bakassian militias surrendered their weapons and returned to civilian life.[32]

The BFF refused to surrender; joining forces with militants in the Niger Delta, they declared that they would destroy the local economy.[37] In December 2009 a police officer was killed off Bakassi in a motorised canoe and the BFF claimed responsibility.[32] On 6 to 7 February 2011, the rebels launched an attack at Limbe and killed two Cameroonians, wounded one, and eleven were missing.[38] In 2012, the BAMOSD launched a national flag[37] and declared independence on 9 August. On the 16th they captured two Cameroonians.[39] In 2013, Cameroon launched a violent crackdown, causing 1,700 people to flee. This angered many Nigerians and prompted the Nigerian government to threaten military intervention. This intervention never materialised.[40]

Aftermath and low-level insurgency

After the agreement, many residents had problems with establishing the recognition of their nationalities in both countries. A lack of identification documents made a number of Nigerians[41] at risk of becoming stateless, after the ceding of Bakassi.[41][42] Since the ceding of Bakassi the Cameroonians have been brutalising and harassing the local Nigerians. According to the academic Agbor Beckly the Cameroonian police want them to leave.[43] Due to the discrimination of the Cameroonians against the locals, most of them were afraid and were in risk to becoming stateless, and many of them decided to not register their children as Cameroonians.[41] On 15 August 2013 the Cameroon government gained full sovereignty over Bakassi and the residents had to pay their first taxes after a 5-year tax-free transition.[5] While militant activity in Bakassi gradually subsided, the cause of the conflict remains unresolved. Since September 2008 more than a third of the local Nigerian population has fled to Nigeria.[4] On 13 February 2015, militants killed a policeman and kidnapped another.[44] In 2017 a diplomatic crisis erupted when it was reported that Cameroonian soldiers had killed 97 Nigerian citizens in Bakassi.[45] This report turned out to be false, and Cameroon subsequently dismissed two village chiefs whom it found responsible for spreading the false news.[46]

By 2018, a major rebellion had broken out in the Cameroon's Anglophone territories which included Bakassi.[47] In May 2019 it was reported that Cameroon police had destroyed the fishing community of Abana, killing at least 40 people.[48] The authorities denied that police personnel had been involved, and blamed a local militia. According to the state government, Cameroonian soldiers subsequently moved into Abana and arrested 15 people suspected of having participated in the killings.[49]

References

- "Cameroon: Moving Toward Independence". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Ngalim, p. 6.

- "Independent Nigeria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "The Lifelong Consequences of a Little-Known Nigeria–Cameroon Land Dispute". TRT World. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Cameroon Forces 'Kill 97 Nigerian Fishermen' in Bakassi". BBC News. 14 July 2017. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Ngalim, p. 2.

- Lukong, p. 2.

- Ngalim, p. 1.

- Egede & Igiehon, p. 2.

- Akinyemi, p. 14.

- Lukong, p. 47.

- Lukong, p. 48.

- "Cameroon – Nigeria". Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Lukong, p. 50.

- Lukong, p. 51.

- "Government of Cameroon - Civilians". Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Lukong, pp. 51–52.

- Akanle & Adésìnà, p. 346.

- Gibler, p. 435.

- Udeoji, p. 92.

- "General Information". Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Lukong, p. 54.

- "Cameroon Takes Control of Disputed Bakassi". VOA News. 14 August 2013. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Udeoji, p. 93.

- "Cameroon–Nigeria Mixed Commission". UNOWAS. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Bakassi Peninsula Dispute". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Bakassi Threatens to Declare Own Republic". This Day Online. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- "Nigeria cedes Bakassi to Cameroon". BBC News. 14 August 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Rebels Declare 'Independence' of Bakassi". Up Station Mountain Club. 31 July 2008. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Troops Clash With Militants, Pirates in Niger Delta – Sahara Reporters". Sahara Reporters. 9 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "70 ans, chef d'État-major des armées" [70, Chief of Staff of the Armed] (in French). 27 April 2009. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Cameroon Rebels Threaten Security in Oil-Rich Gulf of Guinea". Jamestown Foundation. 24 November 2010. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Ngalim, p. 10.

- "Nigeria: Bakassi Leader Dies in Auto Accident". AllAfrica. 18 August 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2016. (registration required)

- "Up to 21 Cameroon Troops Killed in Bakassi". 13 November 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Amoah, p. 156.

- Ngalim, pp. 10–11.

- Ngwa & Funteh, p. 343.

- "Cameroun : le sort des " apatrides " de Bakassi réveille l'instabilité de la presqu'île" [Cameroon: The Plight of 'Stateless' Bakassi Peninsula Creates Instability]. Jeune Afrique (in French). 24 August 2012. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Ngalim, p. 12.

- Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion, p. 3.

- "We're Now Stateless, Bakassi Indigenes Cry Out". Vanguard. 10 June 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Beckly, pp. 67–68, 93.

- Ngwane, p. 2.

- "Killing of 97 in Bakassi Sparks Diplomatic Row Between Cameroon, Nigeria". Journal du Cameroun. 17 July 2017. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Cameroon–Nigeria Row: Two Bakassi Chiefs Dethroned". Journal du Cameroun. 26 July 2017. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Anglophone Cameroon's Separatist Conflict Gets Bloodier". Reuters. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "Nigeria: Cameroonian Gendarmes Kill Scores of Nigerians in Akwa Ibom". AllAfrica. 8 May 2019. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Killings at Fishing Settlement Not by Camerounian Gendarmes – A'Ibom Govt". Independent. 8 May 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

Bibliography

- Akanle, Olayinka; Adésìnà, Jìmí Olálékan (2017). The Development of Africa: Issues, Diagnoses and Prognoses. Cham, Switserland: Springer. ISBN 3319-662-42-2.

- Akinyemi, Omolara (2014). "Borders in Nigeria's Relations with Cameroon". Journal of Arts and Humanities. Cornell University Ithaca. 3 (9). ISSN 2167-9053. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Amoah, M. (2011). Nationalism, Globalization, and Africa. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 1137-002-16-6.

- Beckly, Agbor Tabetah (2013). The Perceptions/Views of Cameroon–Nigerian Bakassi Border Conflict by the Bakassi People (PDF) (Thesis). Historiska institutionen Uppsala universitet. pp. 67–68, 93. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Egede, Edwin E.; Igiehon, Mark Osa (2017). The Bakassi Dispute and the International Court of Justice: Continuing Challenges. New York: Routledge. ISBN 1317-040-74-0.

- Gibler, Douglas M. (2018). International Conflicts, 1816–2010: Militarized Interstate Dispute Narratives. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1442-275-59-6.

- Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion (2018). "Submission to the Human Rights Council at the 30th Session of the Universal Periodic Review: (Third Cycle, May 2018)" (PDF). Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion. Retrieved 5 November 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lukong, Hilary V. (2011). The Cameroon–Nigeria Border Dispute. Management and Resolution, 1981–2011. Mankon, Bamenda: African Books Collective. pp. 2, 47–48, 50–52. ISBN 9956-717-59-2.

- Ngalim, Aloysius Nyuymengka (2016). "African Boundary Conflicts and International Mediation: The Absence of Inclusivity in Mediating the Bakassi Peninsula Conflict" (PDF). Social Science Research Council. 9: 1–2. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Ngwa, Canute Ambe; Funteh, Mark Bolak (2019). Crossing the Line in Africa: Reconsidering and Unlimiting the Limits of Borders within a Contemporary Value. Bermandan, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG. ISBN 9956-550-89-2.

- Ngwane, George (2015). "Preventing Renewed Violence Through Peace Building in the Bakassi Peninsula (Cameroon)" (PDF). Jimbi Central. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Udeoji, Angela Ebele (2013). "The Bakassi Peninsula Zone of Nigeria and Cameroon: The Politics of History in Contemporary African Border Disputes" (PDF). International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Reviews. National Open University of Nigeria. 4 (2): 92–93. ISSN 2276-8645. Retrieved 25 October 2019.