Badarian culture

The Badarian culture provides the earliest direct evidence of agriculture in Upper Egypt during the Predynastic Era. It flourished between 4400 and 4000 BCE,[2] and might have already emerged by 5000 BCE.[1] It was first identified in El-Badari, Asyut Governorate.

| Geographical range | Egypt |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic |

| Dates | circa 5,000 B.C.E.[1] — circa 4,000 B.C.E. |

| Type site | El-Badari |

| Preceded by | Faiyum A culture |

| Followed by | Amratian culture |

| Periods and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All years are BC | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Early

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Ptolemaic (Hellenistic)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

See also: List of Pharaohs by Period and Dynasty Periodization of Ancient Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

About forty settlements and six hundred graves have been located. Social stratification has been inferred from the burying of more prosperous members of the community in a different part of the cemetery. The Badarian economy was based mostly on agriculture, fishing and animal husbandry. Tools included end-scrapers, perforators, axes, bifacial sickles and concave-base arrowheads. Remains of cattle, dogs and sheep were found in the cemeteries. Wheat, barley, lentils and tubers were consumed.

The Badari culture is primarily known from cemeteries in the low desert. The deceased were placed on mats and buried in pits with their heads usually laid to the south, looking west. This seems contiguous with the later dynastic traditions regarding the west as the land of the dead. The pottery that was buried with them is the most characteristic element of the Badarian culture. It had been given a distinctive, decorative rippled surface.

Location and discovery

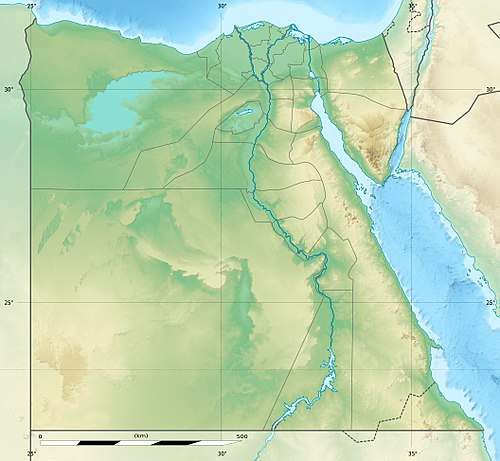

Badari culture is so named because of its discovery at El-Badari (Arabic: البداري), an area in the Asyut Governorate in Upper Egypt. It is located between Matmar and Qau, approximately 200 km northwest of present-day Luxor (ancient Thebes). El-Badari includes numerous Predynastic cemeteries (notably Mostagedda, Deir Tasa and the cemetery of el-Badari itself), as well as at least one early Predynastic settlement at Hammamia. The area stretches for 30 km along the east bank of the Nile. It was first excavated by Guy Brunton and Gertrude Caton-Thompson between 1922 and 1931. Most of the local cemeteries have yielded distinctive pottery vessels (particularly red-polished ware with blackened tops), as well as terracotta and ivory anthropomorphic figures, slate palettes, stone vases and flint tools. The contents of Predynastic cemeteries at el-Badari have been subjected to a number of analyses attempting to clarify the chronology and social history of the Badarian period.

Cultural features

Populations in the Badari culture planted wheat and barley, and kept cattle, sheep, and goats; their livestock was given ceremonial burial. They used boomerangs,[3] fished from the Nile and hunted gazelle. Little is known of their buildings, although remains of wooden stumps have been found at one site and may have been associated with a hut or shelter of unknown construction. Pits that have been found may have served as granaries. Some Badarian sites also show evidence of later predynastic use.[4] The Badarians discovered that malachite could be heated into copper beads.[3] They wore jewelry made of ivory, copper and quartz. Amulets in the shape of animals such as the antelope and hippopotamus have been found.[3]

Badarian grave goods were relatively simple and the deceased wrapped in reed matting or animal skins and placed with personal items such as shells or stone beads. Green malachite ore, perhaps used for personal decoration, has also been detected on stone palettes. Their dead were generally buried facing west, and sometimes accompanied by female mortuary figures carved from ivory.[3]

Trade

Basalt vases found at Badari sites were most likely traded up the river from the Delta region or from the northwest. Shells came in quantities from the Red Sea. Turquoise possibly came from Sinai. A Syrian connection is suggested for a four-handled pot of hard pink ware. The black pottery, with white incised designs, may have come directly from the West, or from the South. The porphyry slabs are like the later ones in Nubia, but the material could have come from the Red Sea Mountains. The glazed steatite beads were not made locally. These all suggest that the Badarians were not an isolated tribe, but were in contact with the cultures on all sides of them. Nor were they nomadic, having pots of such size and fragility that would have been unsuitable for use by wanderers.[5]

Ancestral origins

The Badarian culture seems to have had multiple sources, of which the Western Desert was probably the most influential. Badari culture was likely not to have been solely restricted to the Badari region since related finds have been made farther to the south at Mahgar Dendera, Armant, Elkab and Nekhen (named Hierakonpolis by the Greeks), as well as to the east in the Wadi Hammamat.

Dental trait analysis of Badarian fossils found that they were closely related to other Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting Northeast Africa and the Maghreb. Among the ancient populations, the Badarians were nearest to other ancient Egyptians (Naqada, Hierakonpolis, Abydos and Kharga in Upper Egypt; Hawara in Lower Egypt), and C-Group and Pharaonic era skeletons excavated in Lower Nubia, followed by the A-Group culture bearers of Lower Nubia, the Kerma and Kush populations in Upper Nubia, the Meroitic, X-Group and Christian period inhabitants of Lower Nubia, and the Kellis population in the Dakhla Oasis.[6]:219-20 Among the recent groups, the Badari makers were morphologically closest to the Shawia and Kabyle Berber populations of Algeria as well as Bedouin groups in Morocco, Libya and Tunisia, followed by other Afroasiatic-speaking populations in the Horn of Africa.[6]:222-4 The Badarian skeletons from Kellis were also phenotypically distinct from those belonging to other populations in Sub-Saharan Africa.[6]:231-2

Vase in the shape of a hippopotamus. Early Predynastic, Badarian. 5th millennium BC. From Mostagedda. This vessel is carved from elephant ivory. The fine modeling and attention to detail show the skill in achieving these pieces.

Vase in the shape of a hippopotamus. Early Predynastic, Badarian. 5th millennium BC. From Mostagedda. This vessel is carved from elephant ivory. The fine modeling and attention to detail show the skill in achieving these pieces._-_159.jpg) Ancient Badarian mortuary figurine of a woman, held at the British Museum

Ancient Badarian mortuary figurine of a woman, held at the British Museum

Relative chronology

See also

References

- Watterson, Barbara (1998). The Egyptians. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 31. ISBN 0-631-21195-0.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 479. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- Smith, Homer W. (2015) [1952]. Man and His Gods. Lulu Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781329584952.

- Bard, Kathryn, ed. (2005). Encyclopaedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 0415185890.

- Brunton, Guy; Caton-Thompson, Gertrude (1928). The Badarian Civilisation and Predynastic Remains near Badari. British School of Archaeology in Egypt. ISBN 9780404166250.

- Haddow, Scott Donald. "Dental Morphological Analysis of Roman Era Burials from the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt". Institute of Archaeology, University College London. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.

Sources

- Guy Brunton and Gertrude Caton-Thompson: The Badarian Civilisation and Predynastic Remains near Badari, London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt, 1928.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Badari culture. |

- Badarian Art Badarian figurines in the British Museum

- Badarian Government and Religious Evolution

- The Journal of African History