Aspergillus niger

Aspergillus niger is a fungus and one of the most common species of the genus Aspergillus.

| Aspergillus niger | |

|---|---|

| |

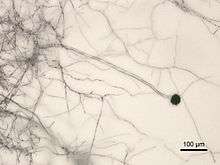

| Micrograph of A. niger grown on Sabouraud agar | |

| |

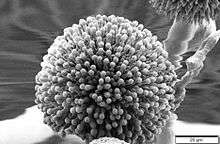

| Details of the head | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Trichocomaceae |

| Genus: | Aspergillus |

| Species: | A. niger |

| Binomial name | |

| Aspergillus niger van Tieghem 1867 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Aspergillus niger var. niger | |

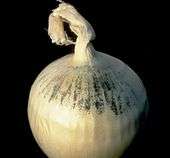

It causes a disease called "black mold" on certain fruits and vegetables such as grapes, apricots, onions, and peanuts, and is a common contaminant of food. It is ubiquitous in soil and is commonly reported from indoor environments, where its black colonies can be confused with those of Stachybotrys (species of which have also been called "black mold").[1]

Some strains of A. niger have been reported to produce potent mycotoxins called ochratoxins;[2] other sources disagree, claiming this report is based upon misidentification of the fungal species. Recent evidence suggests some true A. niger strains do produce ochratoxin A.[1][3] It also produces the isoflavone orobol.

Taxonomy

Aspergillus niger is included in Aspergillus subgenus Circumdati, section Nigri. The section Nigri includes 15 related black-spored species that may be confused with A. niger, including A. tubingensis, A. foetidus, A. carbonarius, and A. awamori.[4][5] A number of morphologically similar species were in 2004 described by Samson et al.[5]

In 2007 the strain of ATCC 16404 Aspergillus niger was reclassified as Aspergillus brasiliensis (refer to publication by Varga et al.[6]). This has required an update to the U.S. Pharmacopoeia and the European Pharmacopoeia which commonly use this strain throughout the pharmaceutical industry.

Pathogenicity

Plant disease

Aspergillus niger causes sooty mold of onions and ornamental plants. Infection of onion seedlings by A. niger can become systemic, manifesting only when conditions are conducive. A. niger causes a common postharvest disease of onions, in which the black conidia can be observed between the scales of the bulb. The fungus also causes disease in peanuts and in grapes.

Human and animal disease

Aspergillus niger is less likely to cause human disease than some other Aspergillus species. In extremely rare instances, humans may become ill, but this is due to a serious lung disease, aspergillosis, that can occur. Aspergillosis is, in particular, frequent among horticultural workers who inhale peat dust, which can be rich in Aspergillus spores. The fungus has also been found in the mummies of ancient Egyptian tombs and can be inhaled when they are disturbed.[7]

A. niger is one of the most common causes of otomycosis (fungal ear infections), which can cause pain, temporary hearing loss, and, only in severe cases, damage to the ear canal and tympanic membrane.

Cultivation

A. niger has been cultivated both on Czapek medium plates and malt extract agar oxoid (MEAOX) plates.

A. niger growing on a Czapek medium plate

A. niger growing on a Czapek medium plate A. niger growing on a MEAOX plate

A. niger growing on a MEAOX plate A. niger under the Foldscope

A. niger under the Foldscope

Industrial uses

Aspergillus niger is cultured for the industrial production of many substances.[8] Various strains of A. niger are used in the industrial preparation of citric acid (E330) and gluconic acid (E574), and have been assessed as acceptable for daily intake by the World Health Organization.[9] A. niger fermentation is "generally recognized as safe" (GRAS) by the United States Food and Drug Administration under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.[10]

Many useful enzymes are produced using industrial fermentation of A. niger.[11] For example, A. niger glucoamylase (P69328) is used in the production of high-fructose corn syrup, and pectinases (GH28) are used in cider and wine clarification. Alpha-galactosidase (GH27), an enzyme that breaks down certain complex sugars, is a component of Beano and other products that decrease flatulence.[12] Another use for A. niger within the biotechnology industry is in the production of magnetic isotope-containing variants of biological macromolecules for NMR analysis.[13] Aspergillus niger is also cultured for the extraction of the enzyme, glucose oxidase (P13006), used in the design of glucose biosensors, due to its high affinity for β-D-glucose.[14][15]

Aspergillus niger growing from gold-mining solution contained cyano-metal complexes, such as gold, silver, copper, iron, and zinc. The fungus also plays a role in the solubilization of heavy-metal sulfides.[16] Alkali-treated A. niger binds to silver to 10% of dry weight. Silver biosorption occurs by stoichiometric exchange with Ca(II) and Mg(II) of the sorbent.

Genetics

Genome

| NCBI genome ID | 429 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | haploid |

| Genome size | 34 Mb |

| Number of chromosomes | 8 |

The A. niger ATCC 1015 genome was sequenced by the Joint Genome Institute in a collaboration with other institutions.[17]

The genomes of two A. niger strains have been fully sequenced.[18][19]

See also

References

- Samson RA, Houbraken J, Summerbell RC, Flannigan B, Miller JD (2001). "Common and important species of fungi and actinomycetes in indoor environments". Microorganisms in Home and Indoor Work Environments. CRC. pp. 287–292. ISBN 978-0415268004.

- Abarca M, Bragulat M, Castellá G, Cabañes F (1994). "Ochratoxin A production by strains of Aspergillus niger var. niger". Appl Environ Microbiol. 60 (7): 2650–2. doi:10.1128/AEM.60.7.2650-2652.1994. PMC 201698. PMID 8074536.

- Schuster E, Dunn-Coleman N, Frisvad JC, Van Dijck PW (2002). "On the safety of Aspergillus niger—a review". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 59 (4–5): 426–35. doi:10.1007/s00253-002-1032-6. PMID 12172605.

- Klich MA (2002). Identification of common Aspergillus species. Utrecht, The Netherlands, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. ISBN 978-90-70351-46-5.

- Samson, RA, Houbraken JA, Kuijpers AF, Frank JM, Frisvad JC (2004). "New ochratoxin A or sclerotium producing species in Aspergillus section Nigri" (PDF). Studies in Mycology. 50: 45–6.

- Varga, J.; Kocsube, S.; Toth, B.; Frisvad, J. C.; Perrone, G.; Susca, A.; Meijer, M.; Samson, R. A. (2007). "Aspergillus brasiliensis sp. nov., a biseriate black Aspergillus species with world-wide distribution". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 57 (8): 1925–32. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.65021-0. PMID 17684283.

- Handwerk, Brian (May 6, 2005) Egypt's "King Tut Curse" Caused by Tomb Toxins?. National Geographic.

- Cairns, TC; Nai, C; Meyer, V (2018). "How a fungus shapes biotechnology: 100 years of Aspergillus niger research". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 5: 13. doi:10.1186/s40694-018-0054-5. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 5966904. PMID 29850025.

- Max, Belén; Salgado, José Manuel; Rodríguez, Noelia; Cortés, Sandra; Converti, Attilio; Domínguez, José Manuel (October 2010). "Biotechnological production of citric acid". Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 41 (4): 862–875. doi:10.1590/S1517-83822010000400005. ISSN 1517-8382. PMC 3769771. PMID 24031566.

- "Inventory of GRAS Notices: Summary of all GRAS Notices". US FDA/CFSAN. 2008-10-22. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- Ong, L. G. A.; Abd-Aziz, S.; Noraini, S.; Karim, M. I. A.; Hassan, M. A. (2004). "Enzyme Production and Profile by Aspergillus niger During Solid Substrate Fermentation Using Palm Kernel Cake as Substrate". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 118 (1–3): 073–080. doi:10.1385/ABAB:118:1-3:073. ISSN 0273-2289. PMID 15304740.

- Di Stefano, Michele; Miceli, Emanuela; Gotti, Samantha; Missanelli, Antonio; Mazzocchi, Samanta; Corazza, Gino Roberto (2007). "The effect of oral alpha-galactosidase on intestinal gas production and gas-related symptoms". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 52 (1): 78–83. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-9296-9. ISSN 0163-2116. PMID 17151807.

- MacKenzie, D. A.; Spencer, J. A.; Le Gal-Coëffet, M. F.; Archer, D. B. (1996-04-30). "Efficient production from Aspergillus niger of a heterologous protein and an individual protein domain, heavy isotope-labelled, for structure-function analysis". Journal of Biotechnology. 46 (2): 85–93. doi:10.1016/0168-1656(95)00179-4. ISSN 0168-1656. PMID 8672288.

- Staiano, M.; Bazzicalupo, P.; Rossi, M.; d'Auria, S. (2005). "Glucose biosensors as models for the development of advanced protein-based biosensors". Molecular BioSystems. 1 (5–6): 354–362. doi:10.1039/b513385h. PMID 16881003.

- Ghoshdastider U, Wu R, Trzaskowski B, Mlynarczyk K, Miszta P, Gurusaran M, Viswanathan S, Renugopalakrishnan V, Filipek S (2015). "Nano-Encapsulation of Glucose Oxidase Dimer by Graphene". RSC Advances. 5 (18): 13570–78. doi:10.1039/C4RA16852F. S2CID 55816037.

- Singh, Harbhajan (2006). Mycoremediation: Fungal Bioremediation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 509. ISBN 978-0470050583.

- "Home – Aspergillus niger ATCC 1015 v4.0".

- Pel H, de Winde J, Archer D, et al. (2007). "Genome sequencing and analysis of the versatile cell factory Aspergillus niger CBS 513.88". Nat Biotechnol. 25 (2): 221–31. doi:10.1038/nbt1282. PMID 17259976.

- Andersen MR, Salazar MP, Schaap PJ, et al. (2011). "Comparative genomics of citric-acid-producing Aspergillus niger ATCC 1015 versus enzyme-producing CBS 513.88". Genome Res. 21 (6): 885–97. doi:10.1101/gr.112169.110. PMC 3106321. PMID 21543515.