Arthur Rhames

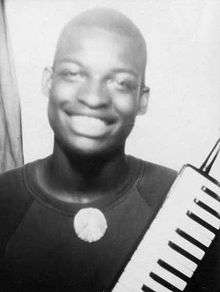

Arthur Rhames (October 25, 1957 – December 27, 1989) was a guitarist, tenor saxophonist, and pianist.

Arthur Rhames | |

|---|---|

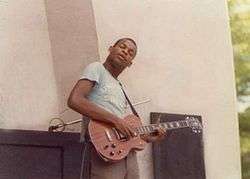

Arthur Rhames with Eternity at the Prospect Park Band Shell c. 1978 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | October 25, 1957 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | December 27, 1989 (aged 32) Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Genres | Free jazz, rock, R&B |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instruments | Piano, guitar, tenor saxophone |

| Years active | 1977–1989 |

| Associated acts | Eternity, Arthur Rhames Trio, Rashied Ali |

Biography

Despite his much-admired technical virtuosity and unmatched dedication - he was notorious among local musicians for daily practice sessions frequently lasting up to 18 hours [1] - the Bedford Stuyvesant-born multi-instrumentalist was unable to secure a recording contract before succumbing to AIDS-related illness at the age of 32 in 1989 in Newark, New Jersey and was interred at the Rosehill Cemetery in Linden, New Jersey.[1][2]

He began his career on the electric guitar in funk/R&B acts in the early Seventies. In 1978, Rhames joined a trio, Eternity, with bassist Cleve Alleyne and drummer Adrian Grannum (later replaced by percussionist Collin Young). He played numerous gigs in the tri-state area as Eternity's guitarist, including annual shows on the Prospect Park soundstage and at several local colleges. While the Mahavishnu Orchestra-inspired power trio remained unsigned, word-of-mouth buzz surrounding the band began to spread, ultimately culminating in a series of dates opening for Larry Coryell's fusion ensemble Eleventh House.[3]

Unfortunately, although these performances won Rhames a great deal of audience acclaim, and even his own Guitar World profile, backstage tensions between Arthur and the concerts' headliner emerged: Coryell refused to acknowledge him as a guitarist, referring to Rhames only as "the piano player." After five or six shows, they left the tour.[4] Nevertheless, Arthur made a cameo appearance as a session player on Coryell's 1978 solo album, ironically titled Difference.[5]

Regardless of the opinions held by some who found him difficult and arrogant (Rhames was considered infamous for his tardiness, in addition to his tendency to respond 'I'm Arthur Rhames!' whenever directly challenged about anything), he exhibited a spiritual side as well. In his Eternity period, or slightly before, he became aware of Swami Prabhupada's expositions of Vaishnava philosophy and the Bhagavad Gita, strongly influencing his worldview. He worshiped at the Hare Krishna Temple on Henry Street in Brooklyn, sometimes with his entire band, and wrote songs (with his bandmates) which reflected Eastern sensibilities in their titles and content, like "Anu Dance."[6]

After Eternity dissolved around 1980, and a long stretch busking as a street musician in and around Manhattan on sax with keyboardist and drummer Charles Telerant, he often collaborated as saxophonist with Coltrane drummer Rashied Ali, eventually incorporating as The Dynamic Duo. They appeared at the 1981 Willisau Jazz Festival in Switzerland. In October of the same year, recordings of his former trio, including pianist John Esposito and drummer Jeff Siegel, were made at a New York club session, featuring impressive interpretations of Coltrane classics "Giant Steps," "Moment's Notice" and "Bessie's Blues," as well as a cover of Albert Ayler's "I Want Jesus To Talk To Me." They were later released on the Japanese DIW label (Live From The Soundscape). Arthur was only 24 years old. In 1988, he re-joined Rashied Ali in a quartet at New York's Knitting Factory.[7]

According to a 1990 interview with Vernon Reid, prior to his death, Rhames was working as a security guard in complete obscurity. However, on the official Arthur Rhames website, former Rhames sideman Charles Telerant states that late in his life, he toured in support of P-Funk's George Clinton as a guitarist, after having shown up to audition in his security uniform.[6] Telerant also relates the following anecdote:

Some years ago I was sitting in the office of Brian Bacchus who was vice president of A&R at Antilles Records at the time. "Who have you played with?" he asked. "A guy from Brooklyn named Arthur Rhames" I replied. "Arthur Rhames?! " he practically screamed. "You played with Arthur Rhames? Where can I find him? I'd sign him right now!" "You can't Brian", I replied. "Arthur died three weeks ago."[6]

Also, Reid said that Rhames was a "deeply closeted" homosexual, and was "afraid that if he was 'out' that all of us in the 'hood who loved and worshipped him as an artist would turn our backs on him." In his final days, ravaged by AIDS, Reid recalls him saying, with complete optimism, "When I get better and get out of here I'm going to concentrate on the blues because this experience has given me a new insight into human suffering." [8]

Reception

- "I've never heard a better guitar player...he was frightening" - Vernon Reid (Living Colour, Masque) [9]

- "Arthur Rhames was one of the greatest musicians God ever put on this Earth" - Rashied Ali (John Coltrane)

- "You couldn't be a musician in Brooklyn and not be influenced by Arthur" - John Purvis (The ReAwakening)[6]

- "Rhames was one of the greatest musical mind of the last forty years" - Cleve Alleyne (Eternity)[3]

- "He was overwhelming. I've never seen the guitar played that way."" - Bill Frisell[6]

- "He played with so much intensity, you thought he was gonna keel over with a heart attack!" -Vernon Reid

- "When he went out onstage, Arthur was about 6-foot-something, a completely sculpted bodybuilder. He had an arrow cut into his head with his hair facing forward. And it was a spectacle to behold when he played. When he played his Sears and Roebuck guitar it looked like the neck was bending like when you make a pencil bend. When he played piano, he absolutely tore it up. He was a big guy who made the instrument shake. The way he played it was unbelievable. When he blew sax, he blew it like he was possessed. So when he went to play with [a well-known jazz musician] people were knocked out by him and he got all the attention. So he lost the gig".[10]

Quotes

- "Improvisation is an intuitive process for me now, but in the way in which it's intuitive, I'm calling upon all the resources of all the years of my playing at once: my academic understanding of the music, my historical understanding of the music, and my technical understanding of the instrument that I'm playing. All these things are going into one concentrated effort to produce something that is indicative of what I'm feeling at the time I'm performing. " - Arthur Rhames[11]

- "Without directly copying his melodic line, I tried to get the feeling of the line, the phrasing, which allowed me to understand how Trane was talking when he played. What I wanted was the form, the basket that he was using, but the contents I wanted to fill myself. I knew that I had something to say, and I wanted to deal with that. So what I copied was the way John constructed his phrases and their rhythmical base, the stems without the notes, and I put my own notes and harmony - the things I thought about - on top of it."[12]

Discography

References

- "News, reviews, interviews and more for top artists and albums – MSN Music". www.msn.com.

- John Esposito:Arthur Rhames Archived 2014-10-14 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 18 May 2012

- "Welcome To Arthur Rhames.net". www.arthurrhames.net.

- "Welcome To Arthur Rhames.net". arthurrhames.net.

- "ARTHUR RHAMES". sudo.3.pro.tok2.com.

- "Welcome To Arthur Rhames.net". www.arthurrhames.net.

- PARELES, JON (1988-01-06). "Jazz: Rashied Ali Quartet". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- "Guide to the Music of Arthur Rhames". RateYourMusic. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Menn, Don (1992). Secrets from the Masters: Conversations with Forty Great Guitar Players. Backbeat Books. p. 196. ISBN 0-87930-260-7.

- "JAMES FINN". www.paristransatlantic.com.

- Begbie, Jeremy (2003). Theology, Music and Time. Cambridge University Press. p. 201. ISBN 0-521-78568-5.

- Berliner, Paul (1994). Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-04381-9.