Aristotle's views on women

Aristotle's views on women influenced later Western thinkers, as well as Islamic thinkers, who quoted him as an authority until the end of the Middle Ages, influencing women's history.

In his Politics, Aristotle saw women as subject to men, but as higher than slaves, and lacking authority; he believed the husband should exert political rule over the wife. Among women's differences from men were that they were, in his view, more impulsive, more compassionate, more complaining, and more deceptive. He gave the same weight to women's happiness as to men's, and in his Rhetoric stated that society could not be happy unless women were happy too. Whereas Plato was open to the potential equality of men and women, stating both that women were not equal to men in terms of strength and virtue, but were equal to men in terms of rational and occupational capacity, and hence in the ideal Republic should be educated and allowed to work alongside men without differentiation, Aristotle appears to have disagreed.

In his theory of inheritance, Aristotle considered the mother to provide a passive material element to the child, while the father provided an active, ensouling element with the form of the human species.

Differences between males and females

Aristotle believed women were inferior to men. For example, in his work Politics (1254b13–14), Aristotle states "as regards the sexes, the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject".[1] In Politics 1.13 he wrote, "The slave is wholly lacking the deliberative element; the female has it but it lacks authority; the child has it but it is incomplete".[2] Cynthia Freeland wrote: "Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity'."[3] Aristotle believed that men and women naturally differed both physically and mentally. He claimed that women are "more mischievous, less simple, more impulsive ... more compassionate ... more easily moved to tears ... more jealous, more querulous, more apt to scold and to strike ... more prone to despondency and less hopeful ... more void of shame or self-respect, more false of speech, more deceptive, of more retentive memory [and] ... also more wakeful; more shrinking [and] more difficult to rouse to action" than men.[4]

He wrote that only fair-skinned women, not darker-skinned women, had a sexual discharge and climaxed. He also believed this discharge could be increased by eating of pungent foods. Aristotle thought a woman's sexual discharge was akin to that of an infertile or amputated male's.[5] He concluded that both sexes contributed to the material of generation, but that the female's contribution was in her discharge (as in a male's) rather than within the ovary.[5]

Aristotle explains how and why the association between man and woman takes on a hierarchical character by commenting on male rule over 'barbarians', or non-Greeks. "By nature the female has been distinguished from the slave. For nature makes nothing in the manner that the coppersmiths make the Delphic knife – that is, frugally – but, rather, it makes each thing for one purpose. For each thing would do its work most nobly if it had one task rather than many. Among the barbarians the female and the slave have the same status. This is because there are no natural rulers among them but, rather, the association among them is between male and female slave. On account of this, the poets say that 'it is fitting that Greeks rule barbarians', as the barbarian and the slave are by nature the same."[6] While Aristotle reduced women's roles in society, and promoted the idea that women should receive less food and nourishment than males, he also criticised the results: a woman, he thought, was then more compassionate, more opinionated, more apt to scold and to strike. He stated that women are more prone to despondency, more void of shame or self-respect, more false of speech, more deceptive, and of having a better memory.[7]

Women's role in inheritance

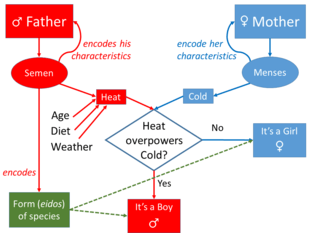

Aristotle's inheritance model sought to explain how the parents' characteristics are transmitted to the child, subject to influence from the environment.[8] In his view, an active, ensouling masculine element brought life to a passive female element.[9] The system worked as follows. The father's semen and the mother's menses encode their parental characteristics.[8][10] The model is partly asymmetric, as only the father's movements define the form or eidos of the human species, while the movements of both the father's and the mother's fluids define features other than the form, such as the father's eye colour or the mother's nose shape.[8] The theory has some symmetry, as semen movements carry maleness while the menses carry femaleness. If the semen is hot enough to overpower the cold menses, the child will be a boy; but if it is too cold to do this, the child will be a girl. Inheritance is thus particulate (definitely one trait or another), as in Mendelian genetics, unlike the Hippocratic model which was continuous and blending.[8] The child's sex can be influenced by factors that affect temperature, including the weather, the wind direction, diet, and the father's age. Features other than sex also depend on whether the semen overpowers the menses, so if a man has strong semen, he will have sons who resemble him, while if the semen is weak, he will have daughters who resemble their mother.[8]

Morality and politics

According to Aristotle, there should be "political rule" of the husband over the wife.[11][12]

As for the differences between husband and wife, Aristotle says that these "always" consisted in external appearances, in speeches, and in honors.[13] The household functions of a man and of a woman are different because his business is "to get" and hers "to keep".[14]

On good wives

In his Economics, Aristotle wrote that it befits not a man of sound mind to bestow his person promiscuously, or have random intercourse with women; for otherwise the base-born will share in the rights of his lawful children, and his wife will be robbed of her honor due, and shame be attached to his sons. It is fitting that he should approach his wife in honor, full of self-restraint and awe, and in his conversation with her, should use only the words of a right-minded man, suggesting only such acts as are themselves lawful and honorable. Aristotle's thought that a wife was best honored when she saw that her husband was faithful to her, and that he had no preference for another woman, but before all others loves, trusts her and holds her as his own.[15] Aristotle wrote that a husband should secure the agreement, loyalty, and devotion of his wife, so that whether he himself is present or not, there may be no difference in her attitude towards him, since she realizes that they are alike guardians of the common interests, and so when he is away she may feel that to her no man is kinder or more virtuous or more truly hers than her own husband.

Spartan women

Aristotle wrote that in Sparta, the legislator wanted to make the whole city (or country) hardy and temperate, and that he carried out his intention in the case of the men, but he overlooked the women, who lived in every sort of intemperance and wealth. He added that in those regimes in which the condition of the women was bad, half the city could be regarded as having no laws.[16]

Equal weight to female and male happiness

Aristotle gave equal weight to women's happiness as he did to men's, and commented in his Rhetoric that a society cannot be happy unless women are happy too. In an article titled "Aristotle's Account of the Subjection of Women", Stauffer explains that Aristotle believed that in nature a common good came of the rule of a superior being. But he does not indicate a common good for men being superior to women. He uses the word κρείττων kreitton to indicate superiority, meaning stronger. Aristotle believed that rational reasoning is what made you superior over lesser beings in nature, yet still used the term meaning stronger, not more rational or intelligent.[6]

Children

On children, he said, "And what could be more divine than this, or more desired by a man of sound mind, than to beget by a noble and honored wife children who shall be the most loyal supporters and discreet guardians of their parents in old age, and the preservers of the whole house? Rightly reared by father and mother, children will grow up virtuous, as those who have treated them piously and righteously deserve that they should..."[17]

Aristotle believed we all have a biological drive to procreate, to leave behind something to take the place and be similar to ourselves. This then justifies the natural partnership between man and woman. And each person has one specific purpose because we are better at mastering one specific trait rather than being adequate at multiple. For Aristotle, women's purpose is to give birth to children. Aristotle stressed that man and woman work together to raise the children and that how they raise them has a huge influence over the kind of people they become and thus the kind of society or community that everyone lives in.

Comparison with Plato's views on women

Aristotle appears to disagree with Plato on the topic whether women ought to be educated, as Plato says that they must be. Both of them, however, consider women to be inferior. Plato in Timaeus (90e) claims that men who were cowards and were lazy throughout their life shall be reborn as women and in the Laws (781b), he offers his reasons why women should be educated: "Because you neglected this sex, you gradually lost control of a great many things which would be in a far better state today if they had been regulated by law. A woman's natural potential for virtue is inferior to a man's, so she's proportionately a greater danger, perhaps even twice as great." Plato further establishes his opinion on the inferiority of women's "natural potential" by claiming in Republic (455d) that "Women share by nature in every way of life just as men do, but in all of them women are weaker than men."

Plato firmly believed in reincarnation and this was very important for the distinction he made between the nature of men and women. This was not the case for Aristotle, who saw the differences as biological. Plato discusses this matter with more detail in Timaeus, where he states that men have a superior soul than women (42a): "Humans have a twofold nature, the superior kind should be such as would from then on be called "man". He added, once again, that men who led bad lives shall be reborn as women (42b): "And if a person lived a good life throughout the due course of his time, he would at the end return to his dwelling place in his companion star, to live a life of happiness that agreed with his character. But if he failed in this, he would be born a second time, now as a woman."

Plato also appears to use the term "womanish" or "female-like" as an derogatory term implying inferiority and emotional instability, as this is clear from Republic 469d and 605e, amongst others.

Legacy

Galen

Aristotle's assumptions on female coldness influenced Galen and others for almost two thousand years until the sixteenth century.[18]

Church Fathers

Joyce E. Salisbury argues that the Church Fathers, influenced by Aristotle's opinions, opposed the practice of independent female ascetism because it threatened to emancipate women from men.[19]

Otto Weininger

In his Sex and Character, written in 1903, Otto Weininger explained that all people are composed of a mixture of the male and the female substance, and that these views are supported scientifically. Weininger cited Aristotle's views in the chapter "Male and Female Psychology" of his book.

See also

- Pseudo-Callicratidas, a Greek philosopher who also wrote about good wives

References

- Smith, Nicholas D. (1983). "Plato and Aristotle on the Nature of Women". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 21 (4): 467–478. doi:10.1353/hph.1983.0090.

- "Aristotle: Politics [Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy] 1260a11". Iep.utm.edu. 27 July 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- Witt, Charlotte; Shapiro, Lisa (1 January 2016). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Feminist History of Philosophy (Spring 2016 ed.).

- History of Animals, 608b1–14.

- Generation of Animals, I, 728a.

- Stauffer, Dana (October 2008). "Aristotle's Account of the Subjection of Women". The Journal of Politics. 70 (4): 929–941. doi:10.1017/s0022381608080973. JSTOR 30219476.

- History of Animals, book IX, part 1.

- Leroi 2014, pp. 215–221.

- Aristotle on woman

- Taylor 1922, p. 50.

- Politics I, 1259a–b.

- Korinna Zamfir, Men and Women in the Household of God: A Contextual Approach to Roles and Ministries in the Pastoral Epistle, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2013, p. 375.

- Politics, 1259b.

- Politics 1277b.

- The Politics and Economics of Aristotle, Edward English Walford and John Gillies, trans. (London: G. Bell & Sons, 1908), pp. 298ff.

- The Politics of Aristotle, Book 2, Ch. 9, trans. Benjamin Jowett, London: Colonial Press, 1900.

- Aristotle, Aristotle's Politics: Writings from the Complete Works: Politics, Economics, Constitution of Athens, Princeton University Press, 2016, p. 254.

- Tuana, Nancy (1993). The Less Noble Sex: Scientific, Religious and Philosophical Conceptions of Women's Nature. Indiana University Press. pp. 21, 169. ISBN 978-0-253-36098-4.

- Joyce E. Salisbury, Church Fathers, Independent Virgins, Verso, 1992.

Sources

- Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Henry Osborn (1922). "Chapter 3: Aristotle's Biology". Greek Biology and Medicine. Archived from the original on 27 March 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)