Apicius

Apicius is a collection of Roman cookery recipes, thought to have been compiled in the 1st century AD and written in a language in many ways closer to Vulgar than to Classical Latin; later recipes using Vulgar Latin (such as ficatum, bullire) were added to earlier recipes using Classical Latin (such as iecur, fervere). Based on textual analysis, the food scholar Bruno Laurioux believes that the surviving version only dates from the fifth century (that is, the end of the Roman Empire): "The history of De Re Coquinaria indeed belongs then to the Middle Ages".[1]

The name "Apicius" had long been associated with an excessively refined love of food, from the habits of an early bearer of the name, Marcus Gavius Apicius, a Roman gourmet and lover of refined luxury, who lived sometime in the 1st century AD during the reign of Tiberius. He is sometimes erroneously asserted to be the author of the book pseudepigraphically attributed to him.

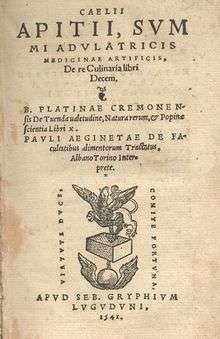

Apicius is a text to be used in the kitchen. In the earliest printed editions, it was usually called De re coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking), and attributed to an otherwise unknown Caelius Apicius, an invention based on the fact that one of the two manuscripts is headed with the words "API CAE"[2] or rather because a few recipes are attributed to Apicius in the text: Patinam Apicianam sic facies (IV, 14) Ofellas Apicianas (VII, 2). It is also known as De re culinaria.

Organization

The Latin text is organized in ten books with Greek titles, in an arrangement similar to that of a modern cookbook:[3]

- Epimeles — The Careful Housekeeper

- Sarcoptes — The Meat Mincer, Ground-beef

- Cepuros — The Gardener, Vegetables

- Pandecter — Many Ingredients

- Ospreon — Pulse, Legumes

- Aeropetes — Birds, Poultry

- Polyteles — The Gourmet

- Tetrapus — The Quadruped, Four-legged animals

- Thalassa — The Sea, Sea-food

- Halieus — The Fisherman

Foods

The foods described in the book are useful for reconstructing the dietary habits of the ancient world around the Mediterranean Basin. But the recipes are geared for the wealthiest classes, and a few contain what were exotic ingredients at that time (e.g., flamingo). A sample recipe from Apicius (8.6.2–3) follows:[4]

- Aliter haedinam sive agninam excaldatam: mittes in caccabum copadia. cepam, coriandrum minutatim succides, teres piper, ligusticum, cuminum, liquamen, oleum, vinum. coques, exinanies in patina, amulo obligas. [Aliter haedinam sive agninam excaldatam] <agnina> a crudo trituram mortario accipere debet, caprina autem cum coquitur accipit trituram.

- Hot kid or lamb stew. Put the pieces of meat into a pan. Finely chop an onion and coriander, pound pepper, lovage, cumin, garum, oil, and wine. Cook, turn out into a shallow pan, thicken with wheat starch. If you take lamb you should add the contents of the mortar while the meat is still raw, if kid, add it while it is cooking.

Alternative editions

In a completely different manuscript, there is also a very abbreviated epitome entitled Apici excerpta a Vinidario, a "pocket Apicius" by "an illustrious man" named Vinidarius, made as late as the Carolingian era.[5] The Vinidarius of this book may have been a Goth, in which case his Gothic name may have been Vinithaharjis (𐍅𐌹𐌽𐌹𐌸𐌰𐌷𐌰𐍂𐌾𐌹𐍃), but this is only conjecture. Despite being called "illustrious," nothing about him is truly known.

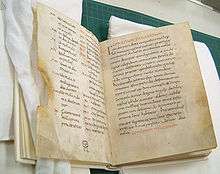

Apici excerpta a Vinidario survives in a single 8th-century uncial manuscript. Despite the title, this booklet is not an excerpt purely from the Apicius text we have today, as it contains material that is not in the longer Apicius manuscripts. Either some text was lost between the time the excerpt was made and the time the manuscripts were written, or there never was a "standard Apicius" text because the contents changed over time as it was adapted by readers.

Once manuscripts surfaced, there were two early printed editions of Apicius, in Milan (1498, under the title In re quoquinaria) and Venice (1500). Four more editions in the next four decades reflect the appeal of Apicius. In the long-standard edition of C. T. Schuch (Heidelberg, 1867), the editor added some recipes from the Vinidarius manuscript.

Between 1498 (the date of the first printed edition) and 1936 (the date of Joseph Dommers Vehling's translation into English and bibliography of Apicius), there were 14 editions of the Latin text (plus one possibly apocryphal edition). The work was not widely translated, however; the first translation was into Italian, in 1852, followed in the 20th century by two translations into German and French. The French translation by Bertrand Guégan was awarded the 1934 Prix Langlois by the Académie française.[6]

Vehling made the first translation of the book into English under the title Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome. It was published in 1936 and is still in print, having been reprinted in 1977 by Dover Publications. It is now of historical interest only, since Vehling's knowledge of Latin was not always adequate for the difficult task of translation, and several later and more reliable translations now exist.

See also

- Medieval cuisine

- Le Viandier – a recipe collection generally credited to Guillaume Tirel, c 1300

- Liber de Coquina – (The book of cooking/cookery) is one of the oldest medieval cookbooks.

- The Forme of Cury – (Method of Cooking, cury being from Middle French cuire: to cook) is an extensive collection of medieval English recipes of the 14th century.

Notes

- Laurioux, Bruno (1994). "Cuisiner à l'Antique : Apicius au Moyen Age". Médiévales. 13 (26): 17-18. doi:10.3406/medi.1994.1294. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Lindsay, p. 144

- The Roman Cookery Book, trans. Flower and Rosenbaum, p. 7.

- The Roman Cookery Book, trans. Flower and Rosenbaum, pp. 188–89.

- Apicius: A Critical Edition with an Introduction and an English Translation, ed. Grocok and Grainger, pp. 309–325.

- "Bertrand GUÉGAN – Académie française". academie-francaise.fr.

Bibliography

Texts and translations

- Apicii decem libri qui dicuntur De re coquinaria ed. Mary Ella Milham. Leipzig: Teubner, 1969. [Latin]

- The Roman Cookery Book: A Critical Translation of the Art of Cooking By Apicius for Use in the Study and the Kitchen. Trans. Barbara Flower and Elisabeth Rosenbaum. London: Harrap, 1958. [Latin and English]

- Apicius: A Critical Edition with an Introduction and an English Translation. Ed. and trans. Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger. Totnes:Prospect Books, 2006. ISBN 1-903018-13-7 [Latin and English]

- Apicius. L'art culinaire. Ed. and trans. Jacques André. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1974. [Latin and French]

- Apicius. Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome. Trans. Joseph Dommers Vehling. 1936. [English]

- The Roman Cookery of Apicius. Trans. John Edwards. Vancouver: Hartley & Marks, 1984. [English]

- Nicole van der Auwera & Ad Meskens, Apicius. De re coquinaria: De romeinse kookkunst. Trans. Nicole van der Auwera and Ad Meskens. Archief- en Bibliotheekwezen in België, Extranummer 63. Brussels, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, 2001. [Dutch]

Secondary material

- Alföldi-Rosenbaum, Elisabeth (1972). "Apicius de re coquinaria and the Vita Heliogabali". In Straub, J., ed., Bonner Historia-Augusta-Colloquium 1970. Bonn, 1972. Pp. 5–18.

- Bode, Matthias (1999). Apicius – Anmerkungen zum römischen Kochbuch. St. Katharinen: Scripta Mercaturae Verlag.

- Déry, Carol. "The Art of Apicius". In Walker, Harlan, ed. Cooks and Other People: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1995. Totnes: Prospect Books. Pp. 111–17.

- Grainger, Sally (2006). Cooking Apicius: Roman Recipes for Today. Totnes: Prospect Books.

- Grainger, Sally (2007). "The Myth of Apicius". Gastronomica, 7(2): 71–77.

- Lindsay, H. (1997). “Who was Apicius?”. Symbolae Osloenses, 72: 144-154.

- Mayo, H. (2008). "New York Academy of Medicine MS1 and the textual tradition of Apicius". In Coulson, F. T., & Grotans, A., eds., Classica et Beneventana: Essays Presented to Virginia Brown on the Occasion of her 65th Birthday. Turnhout: Brepols. Pp. 111–135.

- Milham, Mary Ella (1950). A Glossarial Index to De re coquinaria of Apicius. Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin.

External links

Latin text

| Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Look up apicius in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Bibliotheca Augustana: De Re Coquinaria Libri Decem Mary Ella Milham's edition, nicely presented (Latin)

- Text of the cookbook in Latin at The Latin Library

- Works by Apicius at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Apicius at Internet Archive

- Another version of the Latin text (source not stated)

- Vehling English translation

- Diplomatic version of the Latin text, with parallel English translation and modern redaction of the recipes.