Antonine Plague

The Antonine Plague of 165 to 180 AD, also known as the Plague of Galen (after Galen, the physician who described it), was an ancient pandemic brought to the Roman Empire by troops who were returning from campaigns in the Near East. Scholars have suspected it to have been either smallpox[1] or measles.[2][3] The plague may have claimed the life of a Roman emperor, Lucius Verus, who died in 169 and was the co-regent of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, whose family name, Antoninus, has become associated with the pandemic.

Ancient sources agree that the plague appeared first during the Roman siege of the Mesopotamian city Seleucia in the winter of 165–166.[4] Ammianus Marcellinus reported that the plague spread to Gaul and to the legions along the Rhine. Eutropius stated that a large population died throughout the empire.[5] According to the contemporary Roman historian Cassius Dio, the disease broke out again nine years later in 189 AD and caused up to 2,000 deaths a day in Rome, one quarter of those who were affected.[6] The total death count has been estimated at 5 million,[7] and the disease killed as much as one third of the population in some areas and devastated the Roman army.[8]

Australian sinologist and historian Rafe de Crespigny speculates that the plague may have also broken out in Eastern Han China before 166 because of notices of plagues in Chinese records. The plague affected Roman culture and literature and may have severely affected Indo-Roman trade relations in the Indian Ocean.

Epidemiology

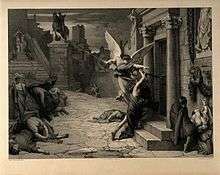

.jpg)

In 166, during the epidemic, the Greek physician and writer Galen travelled from Rome to his home in Asia Minor and returned to Rome in 168, when he was summoned by the two Augusti, the co-emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. He was present at the outbreak among troops stationed at Aquileia in the winter of 168/69. Galen briefly recorded observations and a description of the epidemic in the treatise Methodus Medendi, and he scattered other references to it among his voluminous writings. He described the plague as "great" and of long duration, and mentioned fever, diarrhea, and pharyngitis as well as a skin eruption, sometimes dry and sometimes pustular, that appeared on the ninth day of the illness. The information that was provided by Galen did not clearly define the nature of the disease, but scholars have generally preferred to diagnose it as smallpox.[9]

The historian William H. McNeill[10] asserts that the Antonine Plague and the later Plague of Cyprian (251–ca. 270) were outbreaks of two different diseases, one of smallpox and one of measles but not necessarily in that order. The severe devastation to the European population from the two plagues may indicate that people had no previous exposure to either disease, which brought immunity to survivors. Other historians believe that both outbreaks involved smallpox.[11] The latter view is bolstered by molecular estimates that place the evolution of measles sometime after 1000 AD.[12]

Impact

Arts

In their consternation, many turned to the protection offered by magic. Lucian of Samosata's irony-laden account of the charlatan Alexander of Abonoteichus records a verse of his "which he despatched to all the nations during the pestilence... was to be seen written over doorways everywhere", particularly in the houses that were emptied, Lucian further remarks.[13]

The epidemic had drastic social and political effects throughout the Roman Empire. Barthold Georg Niebuhr (1776–1831) concluded that "as the reign of Marcus Aurelius forms a turning point in so many things, and above all in literature and art, I have no doubt that this crisis was brought about by that plague.... The ancient world never recovered from the blow inflicted on it by the plague which visited it in the reign of Marcus Aurelius."[14] During the Marcomannic Wars, Marcus Aurelius wrote his philosophical work Meditations. A passage (IX.2) states that even the pestilence around him was less deadly than falsehood, evil behaviour and lack of true understanding. As he lay dying, he uttered the words, "Weep not for me; think rather of the pestilence and the deaths of so many others." Edward Gibbon (1737–1794) and Michael Rostovtzeff (1870–1952) assigned the Antonine plague less influence than contemporary political and economic trends, respectively.

Military concerns

Some direct effects of the contagion stand out. When imperial forces moved east, under the command of Emperor Verus, after the forces of Vologases IV of Parthia attacked Armenia, the Romans' defense of the eastern territories was hampered when large numbers of troops succumbed to the disease. According to the 5th-century Spanish writer Paulus Orosius, many towns and villages in the Italian Peninsula and the European provinces lost all of their inhabitants. As the disease swept north to the Rhine, it also infected Germanic and Gallic peoples outside the empire's borders. For years, those northern groups had pressed south in search of more lands to sustain their growing populations. With their ranks thinned by the epidemic, Roman armies were now unable to push the tribes back. From 167 to his death, Marcus Aurelius personally commanded legions near the Danube, trying, with only partial success, to control the advance of Germanic peoples across the river. A major offensive against the Marcomanni was postponed to 169 because of a shortage of imperial troops.

Indian Ocean trade and Han China

Although Ge Hong was the first writer of traditional Chinese medicine who accurately described the symptoms of smallpox, the historian Rafe de Crespigny mused that the plagues afflicting the Eastern Han Empire during the reigns of Emperor Huan of Han (r. 146–168) and Emperor Ling of Han (r. 168–189) – with outbreaks in 151, 161, 171, 173, 179, 182, and 185 – were perhaps connected to the Antonine plague on the western end of Eurasia.[15] De Crespigny suggests that the plagues led to the rise of the cult faith healing millenarian movement led by Zhang Jue (d. 184), who instigated the disastrous Yellow Turban Rebellion (184–205).[16] He also stated that "it may be only chance" that the outbreak of the Antonine plague in 166 coincides with the Roman embassy of "Daqin" (the Roman Empire) landing in Jiaozhi (northern Vietnam) and visiting the Han court of Emperor Huan, claiming to represent "Andun" (安敦; a transliteration of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus or his predecessor Antoninus Pius).[17][18][19]

Raoul McLaughlin wrote that the Roman subjects visiting the Han Chinese court in 166 could have ushered in a new era of Roman Far East trade, but it was a "harbinger of something much more ominous" instead.[20] McLaughlin surmised that the origins of the plague lay in Central Asia, from some unknown and isolated population group, which then spread to the Chinese and the Roman worlds.[20] The plague would kill roughly 10% of the Roman population, as cited by McLaughlin, causing "irreparable" damage to the Roman maritime trade in the Indian Ocean as proven by the archaeological record spanning from Egypt to India as well as significantly decreased Roman commercial activity in Southeast Asia.[21] However, as evidenced by the 3rd-century Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and the 6th-century Christian Topography by Cosmas Indicopleustes, Roman maritime trade into the Indian Ocean, particularly in the silk and spice trades, certainly did not cease but continued until the loss of Egypt to the Muslim Rashidun Caliphate.[22][23] Chinese histories also insist that further Roman embassies came to China by way of Rinan in Vietnam in 226 and 284 AD, where Roman artifacts have been found.[24][25][26]

See also

Notes

- H. Haeser's conclusion, in Lehrbuch der Geschichte der Medicin und der epidemischen Krankenheiten III:24–33 (1882), followed by Zinsser in 1935.

- "There is not enough evidence satisfactorily to identify the disease or diseases", concluded J. F. Gilliam in his summary (1961) of the written sources, with inconclusive Greek and Latin inscriptions, two groups of papyri and coinage.

- The most recent scientific data have eliminated that possibility. See Furuse, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Oshitani, H. (2010). "Origin of the Measles Virus: Divergence from Rinderpest Virus Between the 11th and 12th Centuries". Virology. 7: 52–55. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-7-52.

- Sicker, Martin (2000). "The Struggle over the Euphrates Frontier". The Pre-Islamic Middle East. Greenwood. p. 169. ISBN 0-275-96890-1.

- Eutropius XXXI, 6.24.

- Dio Cassius, LXXII 14.3–4; his book that would cover the plague under Marcus Aurelius is missing; the later outburst was the greatest of which the historian had knowledge.

- "Past pandemics that ravaged Europe". BBC News. November 7, 2005.

- Smith, Christine A. (1996). "Plague in the Ancient World". The Student Historical Journal.

- See McLynn, Frank, Marcus Aurelius, Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, Vintage Books, London, 2009.

- McNeill, W.H. 1976 Plagues and Peoples. New York Anchor Press. ISBN 0-385-11256-4

- D. Ch. Stathakopoulos Famine and Pestilence in the late Roman and early Byzantine Empire (2007) 95

- Furuse Y, Suzuki A, Oshitani H (2010), "Origin of measles virus: divergence from rinderpest virus between the 11th and 12th centuries.", Virol. J., 7 (52)

- Lucian, Alexander, 36.

- Niebuhr, Lectures on the history of Rome III, Lecture CXXXI (London 1849), quoted by Gilliam 1961:225

- de Crespigny, Rafe. (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, p. 514, ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- de Crespigny, Rafe. (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, pp. 514–515, ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- de Crespigny, Rafe. (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, p. 600, ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- See also Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1999). "The Roman Empire as Known to Han China". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (1): 71–79. doi:10.2307/605541.

- See also: Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1, p. 27.

- Raoul McLaughlin (2010), Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India, and China, London & New York: Continuum, ISBN 978-1847252357, p. 59.

- Raoul McLaughlin (2010), Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India, and China, London & New York: Continuum, ISBN 978-1847252357, pp. 59–60.

- Yule, Henry (1915). Henri Cordier (ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route. London: Hakluyt Society, p. 25. Accessed 21 September 2016.

- William H. Schoff (2004) [1912]. Lance Jenott (ed.). "'The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century' in The Voyage around the Erythraean Sea". Depts.washington.edu. University of Washington. Retrieved 2016-09-21.

- Warwick Ball (2016), Rome in the East: Transformation of an Empire, 2nd edition, London & New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-72078-6, pp. 152–153.

- Yule, Henry (1915). Henri Cordier (ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route. London: Hakluyt Society, pp. 53–54. Accessed 21 September 2016.

- Gary K. Young (2001), Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC – AD 305, London & New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-24219-3, p. 29.

References

- Bruun, Christer, "The Antonine Plague and the 'Third-Century Crisis'," in Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn, Danielle Slootjes (ed.), Crises and the Roman Empire: Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire, Nijmegen, June 20–24, 2006. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2007 (Impact of Empire, 7), 201–218.

- Gilliam, J. F. "The Plague under Marcus Aurelius". American Journal of Philology 82.3 (July 1961), pp. 225–251.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Littman, R.J. and Littman, M.L. "Galen and the Antonine Plague". American Journal of Philology, Vol. 94, No. 3 (Autumn, 1973), pp. 243–255.

- Marcus Aurelius. Meditations IX.2. Translation and Introduction by Maxwell Staniforth, Penguin, New York, 1981.

- McNeill, William H. Plagues and Peoples. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., New York, 1976. ISBN 0-385-12122-9.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. "The Roman Empire as Known to Han China", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 119, (1999), pp. 71–79

- de Crespigny, Rafe. (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, pp. 514–515, ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- Zinsser, Hans. Rats, Lice and History: A Chronicle of Disease, Plagues, and Pestilence (1935). Reprinted by Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc. in 1996. ISBN 1-884822-47-9.