Anal gland

The anal glands or anal sacs are small glands near the anus in many mammals, including dogs[1] and cats. They are paired sacs on either side of the anus between the external and internal sphincter muscles. Sebaceous glands within the lining secrete a liquid that is used for identification of members within a species. These sacs are found in many carnivorans, including wolves,[2] bears,[3][4] sea otters[5] and kinkajous.[6]

Humans

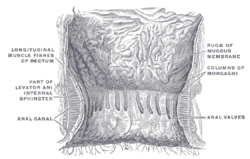

The anal glands are in the wall of the anal canal. They secrete into the anal canal via anal ducts which open into the anal crypts along the level of the dentate line. The glands are at varying depths in the anal canal wall, some between the layers of the internal and external sphincter (the intersphincteric plane). The cryptoglandular theory states that obstruction of these ducts, presumably by accumulation of foreign material (e.g. fecal bacterial plugging) in the crypts, may lead to perianal abscess and fistula formation.[7][8]

Dogs and cats

Dogs and cats primarily use their anal gland secretions to mark their territory, and generally will secrete small amounts of fluid every time they defecate. Many will often express these glands when anxious or frightened as well. Anal sac fluid varies from yellow to tan or brown in color. The consistency of the fluid ranges from thin, watery secretions to thick, gritty paste.

The inability to effectively express this fluid can lead to anal sacculitis. This is characterized by a build-up of fluid in the anal sac, an uncomfortable condition that can lead to pain and itching. Dogs and cats of any age may be affected, but dogs are far more likely to suffer from anal sacculitis than cats. Dogs and cats with anal glands that do not express naturally may exhibit specific signs, such as scooting the backside upon the ground, straining to defecate, and excessive licking of the anus. Cats may also defecate in areas outside the litter box.[9]

Discomfort may also be evident with impaction or infection of the anal glands. Anal sac impaction results from blockage of the duct leading from the gland to the opening. The sac is usually non-painful and swollen. Anal sac infection results in pain, swelling, and sometimes abscessation and fever.

Initial treatment usually involves the manual expression of the anal sacs, most often by a veterinary professional. The frequency of this procedure depends on the patient's individual degree of discomfort but can range from weekly to every few months.[9] Treatment may include lancing of an abscess or antibiotic infusion into the gland in the case of infection. The most common bacterial isolates from anal gland infection are E. coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Clostridium perfringens, and Proteus species.[10] Increasing dietary fiber is also commonly recommended.[9]

Anal sacs may be removed surgically in a procedure known as anal sacculectomy. This is usually done in the case of recurrent infection or because of the presence of an anal sac adenocarcinoma, a malignant tumor. Potential complications include fecal incontinence (especially when both glands are removed), tenesmus from stricture or scar formation, and persistent draining fistulae.[11]

Opossums

Opossums use their anal glands when they "play possum". As the opossum mimics death, the glands secrete a foul-smelling liquid, suggesting the opossum is rotting. Opossums are not members of the carnivora, and that their anal sacs differ from those of dogs and their relatives.[6]

Skunks

Skunks use their anal glands to spray a foul-smelling and sticky fluid as a defense against predators.

Beavers

An extraction of castoreum, the scent glands from the male and female beaver are used in perfumery and as a flavor ingredient.

See also

References

- Howard E. Evans; Alexander de Lahunta (7 August 2013). Miller's Anatomy of the Dog - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-26623-9.

- L. David Mech; Luigi Boitani (1 October 2010). Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51698-1.

- Rosell, F.; Jojola, S. M.; Ingdal, K.; Lassen, B. A.; Swenson, J. E.; Arnemo, J. M.; Zedrosser, A. (Feb 2011). "Brown bears possess anal sacs and secretions may code for sex" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 283 (2): 143–152. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00754.x. hdl:11250/2437930.

- Dyce, K.M.; Sack, W.O.; Wensing, C.J.G. (1987). Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy. W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-1332-2.

- Kenyon, Karl W. (1969). The Sea Otter in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife.

- Ford, L. S.; Hoffman, R. S. (1988-12-27). "Potos flavus". Mammalian Species. American Society of Mammalogists. 321 (321): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504086. JSTOR 3504086.

- Yamada, Tadataka; Alpers, David H.; Kalloo, Anthony N.; Kaplowitz, Neil; Owyang, Chung; Powell, Don W., eds. (2009). Textbook of gastroenterology (5th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-1-4051-6911-0.

- Wolff, Bruce G.; Pemberton, John H.; Wexner, Steven D.; Fleshman, James W.; Beck, David E., eds. (2007). The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-24846-2.

- "Anal sacculitis in dogs | Vetlexicon Canis from Vetstream | Definitive Veterinary Intelligence". www.vetstream.com. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.

- Hill LM, Smeak DD (2002). "Open versus closed bilateral anal sacculectomy for treatment of non-neoplastic anal sac disease in dogs: 95 cases (1969–1994)". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 221 (5): 662–5. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.221.662. PMID 12216905.