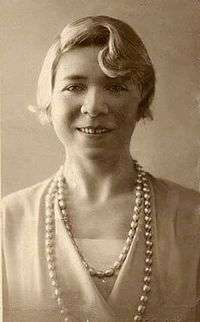

Alfonsina Storni

Alfonsina Storni (29 May 1892 – 25 October 1938) was an Argentine poet of the modernist period.[1]

Alfonsina Storni | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 29 May 1892 Sala Capriasca, Switzerland |

| Died | 25 October 1938 (aged 46) Mar del Plata, Argentina |

| Resting place | La Chacarita Cemetery |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | Ocre ("Ochre") El dulce daño ("Sweet pain") |

| Signature |  |

Early life

Storni was born on May 29, 1892 in Sala Capriasca, Switzerland. Her parents were Alfonso Storni and Paola Martignoni, who were of Italian-Swiss descent. Before her birth, her father had started a brewery in the city of San Juan, Argentina, producing beer and soda. In 1891, following the advice of a doctor, he returned with his wife to Switzerland, where Alfonsina was born the following year; she lived there until she was four years old. In 1896 the family returned to San Juan, and a few years later, in 1901, moved to Rosario because of economic issues. There her father opened a tavern, where Storni did a variety of chores. That family business soon failed, however. Storni wrote her first verse at the age of twelve, and continued writing verses during her free time. She later entered into the Colegio de la Santa Union as a part-time student.[2] In 1906, her father died and she began working in a hat factory to help support her family.[2]

In 1907, her interest in dance led her to join a traveling theatre company, which took her around the country. She performed in Henrik Ibsen's Ghosts, Benito Pérez Galdós's La loca de la casa, and Florencio Sánchez's Los muertos. In 1908, Storni returned to live with her mother, who had remarried and was living in Bustinza. After a year there, Storni went to Coronda, where she studied to become a rural primary schoolteacher. During this period, she also started working for the local magazines Mundo Rosarino and Monos y Monadas, as well as the prestigious Mundo Argentino.

In 1912 she moved to Buenos Aires, seeking the anonymity afforded by a big city. There she met and fell in love with a married man whom she described as "an interesting person of certain standing in the community. He was active in the politics..."[2] That year, she published her first short story in Fray Mocho.[2] At age nineteen, she found out that she was pregnant with the child of a journalist and became a single mother.[2] Supporting herself with teaching and newspaper journalism, she lived in Buenos Aires where the social and economical difficulties faced by Argentina's growing middle classes were inspiring an emerging body of women's rights activists.[3]

Literary career

Storni was among the first women to find success in the male-dominated arenas of literature and theater in Argentina, and as such, developed a unique and valuable voice that holds particular relevance in Latin American poetry.[3] Storni was an influential person, not only to her readers but also to other writers.[4] Though she was known mainly for her poetic works, she also wrote prose, journalistic essays, and drama.[4] Storni often gave controversial opinions.[2] She criticized a wide range of topics from politics to gender roles and discrimination against women.[2] In Storni's time, her work did not align itself with a particular movement or genre. It was not until the modernist and avant-garde movements[5] began to fade that her work seemed to fit in. She was criticized for her atypical style, and she has been labeled most often as a postmodern writer.[6]

Early work

Storni published some of her first works in 1916 in Emin Arslan's literary magazine La Nota, where she was a permanent contributor from 28 March until 21 November 1919.[7][4][8] Her poems “Convalecer” and “Golondrinas” were published in the magazine. In spite of economic difficulties, she published La inquietud del rosal in 1916, and later started writing for the magazine Caras y Caretas while working as a cashier in a shop. Even though today Storni's early works of poetry are among her most well known and highly regarded, they received harsh criticism from some of her male contemporaries, including such well known figures as Jorge Luis Borges and Eduardo Gonzalez Lanuza.[9] The eroticism and feminist themes in her writing were controversial subject matter for poetry during her time, but writing about womanhood in such a direct way was one of her principal innovations as a poet.[10]

Wider recognition

In the rapidly developing literary scene of Buenos Aires, Storni soon became acquainted with other writers, such as José Enrique Rodó and Amado Nervo. Her economic situation improved, which allowed her to travel to Montevideo, Uruguay. There she met the poet Juana de Ibarbourou, as well as Horacio Quiroga, with whom she would become great friends. Quiroga led the Anaconda group and Storni became a member[11] together with Emilia Bertolé, Ana Weiss de Rossi, Amparo de Hieken, Ricardo Hicken and Berta Singerman[12]

During one of her most productive periods, from 1918-1920 Storni published three volumes of poetry: El dulce daño (Sweet Pain), 1918; Irremediablemente (Irremediably), 1919; and Languidez (Languor) 1920. The latter received the first Municipal Poetry Prize and the second National Literature Prize, which added to her prestige and reputation as a talented writer.[3] she also published many articles in prominent newspapers and journals of the time.[13] Later, she continued her experimentation with form in 1925's Ocre, a volume composed almost entirely of sonnets that are among her most traditional in structure. These verses were written around the same time as the more loosely structured prose poems of her lesser-known volume, Poemas de Amor, from 1926.[14]

Theater

After the critical success of Ocre, Storni decided to focus on writing drama. Her first public work, the autobiographical play El amo del mundo was performed in the Cervantes theater on March 10, 1927, but was not well received by the public. However, this was not a conclusive indication of the quality of the work; many critics have observed that during those years Argentinian theater as a whole was in a state of decline, so many quality works of drama failed in this atmosphere.[15] After the play's short run, Storni had it published in Bambalinas, where the original title is shown to have been Dos mujeres.[16] Her Dos farsas pirotécnicas were published in 1931.

Escribió las siguientes obras infantiles: "Blanco...Negro...Blanco", "Pedro y Pedrito", "Jorge y su Conciencia", "Un sueño en el camino", "Los degolladores de estatuas" y "El Dios de los pájaros". Fueron piezas teatrales breves de comedia con canciones y danzas. Estaban destinadas a sus estudiantes del Teatro Labardén. De "Pedrito y Pedro" y "Blanco...Negro...Blanco", Alfonsina, creó la música de las obras. Las mismas fueron puestas en escenas en 1948 en el Teatro Colón de Buenos Aires. Julieta Gómez Paz dice: "Plantean, irónicamente, situaciones trasladadas al mundo infantil para señalar errores, prejuicios y dañinas costumbres adultas, corregidas por la fantasía poética en desenlaces felices." [17]

Later work

After a nearly 8-year hiatus from publishing volumes of poetry, Storni published El mundo de siete pozos (The World of Seven Wells), 1934. That volume, together with the final volume she published before her death, Mascarilla y trébol (Mask and Clover), 1938, mark the height of her poetic experimentation. The final volume includes the use of what she termed "antisonnets," or poems that used many of the versification structures of traditional sonnets but did not follow the traditional rhyme scheme.[18]

Illness and death

In 1935, Storni may have discovered a lump on her left breast and decided to undergo an operation. On May 20, 1935, she underwent a radical mastectomy.[2] In 1938 she found out that the breast cancer had reappeared.[2] Around 1:00 AM on Tuesday, 25 October 1938. Storni left her room and headed towards the sea at La Perla beach in Mar del Plata, Argentina and died by suicide. Later that morning two workers found her body washed up on the beach. Although her biographers hold that she jumped into the water from a breakwater, popular legend is that she slowly walked out to sea until she drowned. She is buried in La Chacarita Cemetery.[19] Her death inspired Ariel Ramírez and Félix Luna to compose the song "Alfonsina y el Mar" ("Alfonsina and the Sea").[20]

Work

- 1916 La inquietud del rosal ("The Restlessness of the Rosebush")[21]

- 1916 Por los niños que han muerto("For the kids that have died")[22]

- 1916 Canto a los niños("Sing to the Children")[22]

- 1918 El dulce daño ("The Sweet Harm")[21]

- 1918 Atlántida colaboracion.[23]

- 1919 Irremediablemente ("Irremediably")[21]

- 1919 Una golondrina [22]

- 1920 Languidez ("Languidness")[21]

- 1925 Ocre ("Ochre")[21]

- 1926 Poemas de amor ("Love poems")[21]

- 1927 El amo del mundo: comedia en tres actos - play ("Master of the world: a comedy in three acts" [21]

- 1932 Dos farsas pirotécnicas - play ("Two pyrotechnic farces")[21]

- 1934 Mundo de siete pozos ("World of seven wells")[21]

- 1938 Mascarilla y trébol ("Mask and trefoil")[21]

- 1938 I am Going to Sleep[21]

Some of Storni's work

Teeth of flowers, cap of dew hands of grass, you, kind nurse, have ready for me sheets of earth and the eiderdown of fresh moss

I shall sleep now, my nurse; help me to bed. Put a lamp at the head; a constellation, whichever you choose; all are fine; turn down a light a bit.

Leave me now; hear the buds bursting... from above a heavenly foot will rock you and a bird will sing to you

that you might forget... Thank you. Ah, One request! If he should phone again, tell him not to persist, for I have left...

Post mortem:

Awards and recognition

In 1910 she receives her title as "Maestra Rural"[2]

In 1917 Storni receives the Premio Annual del Consejo Nacional de Mujeres.[2]

In 1920 Languidez, one of her publications was awarded the First Municipal prize as well as the second National Literature Prize.[2]

References

- Salem Press (1 October 1999). Directory of Historical Figures. Salem Press. p. 604. ISBN 978-0-89356-334-9. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Jones, Sonia (1979). Alfonsina Storni. Internet Archive. Boston : Twayne Publishers.

- Bowen, Kate (10 November 2011). "Alfonsina Storni: The Poetess that Broke from the Pack". The Argentina Independent. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- Méndez, Claudia Edith (28 July 2004). "Alfonsina Storni: Análisis y contextualización del estilo impresionista en sus crónicas". Digital Repository. Languages, Literatures, & Cultures Theses and Dissertations (in Spanish). College Park, MD: University of Maryland. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Pascucci, Michele M. (2016). "Mensajeros de un tiempo nuevo: Modernidad y nihilismo en la literatura de vanguardia (1918–1936) by Juan Herrero Senés". Hispania. 99 (3): 495–496. doi:10.1353/hpn.2016.0077. ISSN 2153-6414.

- "Alchemy » "The Dream"". alchemy.ucsd.edu. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- Diz, Tania (2005). "Periodismo y tecnologías de género en la revista La Nota- 1915-18" (PDF). Revista Científica de la Universidad de Ciencias Empresariales y Sociales (in Spanish). Buenos Aires. IX (1): 89–108. ISSN 1514-9358. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Quereilhac, Soledad (20 June 2014). "Con la mira en la mujer futura". La Nación (in Spanish). Buenos Aires. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Kirkpatrick, Gwen. "The Journalism of Alfonsina Storni: A New Approach to Women's History in Argentina". Seminar on Feminism and Culture in Latin America. Women, Culture, and Politics in Latin America. University of California Press. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Geasler Titiev, Janice (1978). "Feminist Themes in Alfonsina Storni's Poetry". Letras Femeninas. 4 (1): 39–40. JSTOR 23022498.

- Delgado, Josefina (2012-02-01). Alfonsina Storni: Una biografía esencial (in Spanish). Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial Argentina. ISBN 978-987-566-776-1.

- Quiroga, Horacio (1996). Todos los cuentos (in Spanish). EdUSP. ISBN 978-84-89666-25-2.

- Jones, Sonia (1979). Alfonsina Storni. Twayne Publishers. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0805763600.

- Geasler Titiev, Janice (Winter 1980). "Alfonsina Storni's "Poemas de amor": Submissive Woman, Liberated Poet". Journal of Spanish Studies: Twentieth Century Journal of Spanish Studies: Twentieth Century. 8 (3): 279–292. JSTOR 27740950.

- Phillips, Rachel (1975). Alfonsina Storni: From Poetess to Poet. London: Tamesis Books Limited. p. 61. ISBN 0729300013.

- Phillips, Rachel (1975). Alfonsina Storni: From Poetess to Poet. London: Tamesis Books Limited. p. 62. ISBN 0729300013.

- Storni, Alfonsina (1984). Obras Escogidas Teatro. Editorial Columba S. A.: Jorge R. Corvalan. p. 6. ISBN 950-9422-00-2.

- Kuhnheim, Jill (Autumn 2008). "The Politics of Form: Three Twentieth-Century Spanish American Poets and the Sonnet" (PDF). Hispanic Review: 391. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Alfonsina Storni". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

- Global, Voluntario. "Argentine Women - Working Towards Equality - Volunteer Opportunities in Argentina". Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "Alfonsina Storni - Alfonsina Storni Biography - Poem Hunter".

- "Alfonsina Storni - Poemas de Alfonsina Storni".

- "Historia y biografía de Alfonsina Storni". 2017-10-05.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfonsina Storni. |

- Alfonsina at the Cervantes Virtual Library (Spanish)

- Alfonsina by Agriela Deccicco (Spanish)

- Alfonsina, a 1957 film starring Amelia Bence (Spanish)

- Translation of Storni's poem Peso Ancestral (English)