Alexandros Schinas

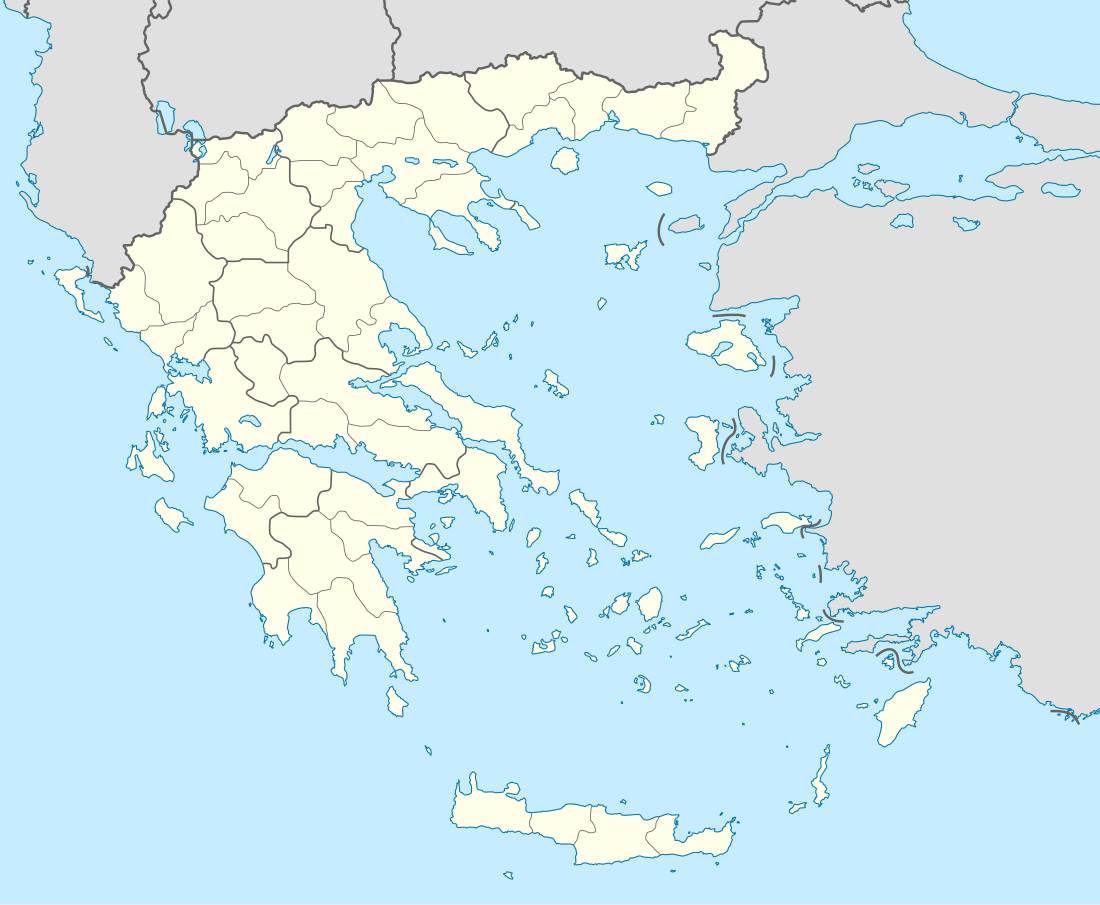

Alexandros Schinas (Greek: Αλέξανδρος Σχινάς, c. 1870 – May 6, 1913), also known as Aleko Schinas, assassinated King George I of Greece in 1913. Schinas has been variously portrayed as either an anarchist with political motivations (propaganda by deed), or a madman, but the historical record is inconclusive. The details of the assassination itself are known: on March 18, 1913, several months after Thessaloniki's liberation from the Ottoman Empire during the First Balkan War, King George I was out for a late afternoon walk in the city, and, as was his custom, lightly guarded. Encountering George on the street near the White Tower, Schinas shot the king once in the back from close range with a revolver, killing him. Schinas was arrested and tortured. He claimed to have acted alone, blaming his actions on delirium brought on by tuberculosis. After several weeks in custody, Schinas died by falling out of a police station window, either by murder or by suicide.

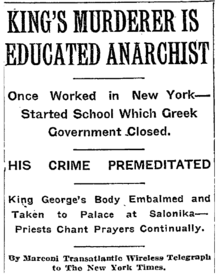

The details of Schinas's life before the assassination are unclear. He was a native Greek but his birthplace is disputed, likely either in the area of Volos or Serres. His occupation is also unconfirmed. Several years before the assassination, Schinas may have left Greece for New York City, returning in February 1913. Some contemporary sources reported that he advocated anarchism or socialism, and ran an anarchist school that was shut down by the Greek government. Other sources claim he was mentally ill, a foreign agent, or held a grudge against the king. Since his death, his true motivations have been the subject of much dispute.

Early life

Very little is confirmed about Schinas's life before he assassinated King George I.[1] He was born in the 1870s, possibly in Volos,[2] Serres,[3] or Kanalia.[4] He had two sisters, one older and one younger, and may have had a brother named Hercules who ran a chemist shop in Volos, where Schinas may have worked as an assistant. Schinas told an interviewer that he suffered from an unspecified "neurological condition" beginning at age 14.[5] Schinas may have studied or taught medicine in Athens, possibly at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. After leaving Athens, Schinas and his sisters taught in the Greek village Kleisoura before a dispute with his older sister forced him to resign. Schinas then moved to Xanthi and practiced medicine without authorization until stopped by authorities.[6]

Schinas's life after Xanthi is the subject of some dispute. Demetrios Botassi, the Greek consul general for New York in 1913, and other New York Greeks, told The New York Times that Schinas moved to Volos to open a school called the Centre for Workingmen with a doctor and a lawyer. The school was closed down by the government within months for "teaching anti-government ideas", and the doctor and lawyer were sentenced to three months in prison. For reasons unknown, Schinas was not punished. According to Botassi, during this period, Schinas also stood unsuccessfully as a candidate for the office of deputy from Volos in the Greek legislative body.[7]

Botassi's account was disputed by Bazil Batznoulis in a letter to Atlantis, a Greek paper in New York, which was republished by The New York Times shortly after the assassination. Batznoulis claimed that Schinas was born in Kanalia, not Volos. According to Batznoulis's letter, it was not Alexandros Schinas who ran for office in Volos, but another person named George Schinas. Batznoulis disputed that Alexandros Schinas was involved in the Centre for Workingmen school in Volos, writing: "Schinas had nothing to do with any school and had no idea of entering politics. He was known as a man who loved isolation and his backgammon. He wore a beard and was an anarchist."[8]

In the years prior to the assassination, Schinas reportedly lived in New York City and worked at the Fifth Avenue Hotel and Plaza Hotel. Schinas stated in a 1913 interview that in 1910, he was deported from Thessaloniki (then under Ottoman rule) by the Young Turks "because I was a good Greek patriot".[9] Botassi suggested another explanation for Schinas's departure to the US: that he was evading the police following the closure of the Centre for Workingmen school in Volos. Batznoulis, on the other hand, wrote that Schinas left because of a family quarrel with his brother Hercules.[10]

No known immigration or other records document Schinas's deportation from Thessaloniki or arrival in New York in 1910. However, immigration records document the arrival of a 36-year-old man named Athanasios Schinas (approximately the same age as Alexandros Schinas would have been at the time), a former resident of Kalavryta, Greece, arriving at Ellis Island aboard the ship La Gascogne from Le Havre, France on October 30, 1905. It is unclear whether Athanasios Schinas was the same person as Alexandros, or whether Alexandros travelled under an assumed name to avoid detection by Greek authorities.[10] In apparent contrast to reports of his emigration in 1910, a 1913 article in The New York Times reported that Schinas was still in Greece in 1911, stating that he applied that year for assistance at the king's palace but was refused and driven off by palace guards.[11]

Although it is uncertain when, why, or even whether he moved to New York City, Schinas was back in Greece by February 1913. According to post-assassination newspaper articles, about three weeks before the assassination, he traveled from Athens to Volos, then to Thessaloniki, possibly subsisting by begging. In an interview while in custody, Schinas stated that some weeks prior the assassination, he had contracted tuberculosis, and a few days before the assassination, he was suffering from "severe high fevers" and "deliriums", and "was being taken over by madness".[12]

Assassination of King George I

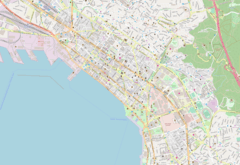

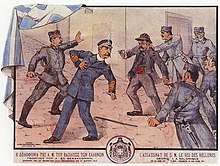

George I was elected King of Greece at age 17 and ruled for nearly 50 years. By the time Schinas arrived in Thessaloniki, George had been staying there for several months, planning a celebration following the city's liberation from the Ottomans during the First Balkan War.[13] On March 18, 1913, George took his usual afternoon walk, accompanied by Greek Army officer Ioannis Frangoudis. Against the urging of his advisers, the king refused to travel the city with a large number of guards; only two gendarmerie police officers were permitted to follow at a distance.[14] George and Frangoudis walked by the harbor near the White Tower of Thessaloniki, discussing the king's upcoming visit to the German battleship SMS Goeben. At approximately 5:15 p.m., on the corner of Vassilissis Olgas and Aghias Triadas streets,[15] Schinas shot George once in the back at point-blank range with a seven-cylinder revolver.[16] The bullet entered below the shoulder blade, pierced the heart and lungs, and exited the abdomen.[17] George collapsed and was taken by carriage to a nearby hospital. He died before arriving.[18][19]

According to The New York Times, Schinas had "lurked in hiding" and "rushed out" to shoot George.[2] Another version described Schinas emerging from a Turkish cafe called the "Pasha Liman", drunk and "ragged", and shooting the king when he walked by.[20] Schinas did not attempt to escape afterwards and Frangoudis immediately apprehended him. Additional gendarmerie arrived quickly from a nearby police station. Schinas reportedly asked the police to protect him from the surrounding crowd.[21] At the hospital, George's third son Prince Nicholas announced that George's eldest son Constantine I was now king.[22] Newspapers reported "sorrow" in Thessaloniki following the assassination[23] and "spectators burst[ing] into tears" at the king's funeral procession the following day.[2]

Death

Schinas was tortured or "forced to undergo examinations" while in gendarmerie custody.[24] He did not name any accomplices. In a 1913 interview, Schinas was asked if his assassination of the king was premeditated, to which he replied:[9]

No! I assassinated the King by chance (it just happened). I was walking as a dead man (as a zombie) without knowing where I was going. Suddenly by turning my head I saw behind me the King with his adjutant. I slowed my pace. The King walked by me, very close to me. I let him walk by me and immediately, I fired.

On May 6, 1913, six weeks after being arrested, Schinas died by falling thirty feet (nine metres) out of a window from the office of the Examining Magistrate of the gendarmerie in Thessaloniki. He was approximately 43 years old.[25] The gendarmerie reported that Schinas, who was not handcuffed at the time, ran and jumped out of the window when the guards were distracted.[26] Some suggest Schinas may have committed suicide to avoid further gendarmerie "examinations" or a slow death from tuberculosis; others speculate that he was thrown from the window by the gendarmerie.[27] Greek newspaper Kathimerini has reported that Schinas gave depositions before his death, but they were lost in a fire aboard a ship while being transported.[28] After his death, his ear and hand were amputated and used for identification, then stored and exhibited at the Criminology Museum of Athens.[29]

Motives

Schinas is understood to have been, in his later life, a homeless alcoholic with anarchist beliefs.[30] Accordingly, his motivation for the assassination is commonly ascribed to his anarchist politics (as propaganda of the deed)[31] or to mental illness (without political motivation).[32][33] Ultimately, the historical record is inconclusive.[34]

Political

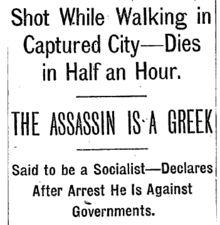

Schinas has been described as an anarchist[31] and a socialist.[35] The March 19, 1913, initial report of George's assassination in The New York Times described Schinas as "a Socialist" who declared that "he is against governments". However, it also described him as a "feeble intellect" and "of low mental type", "who states that he was driven to desperation by sickness and want", concluding: "The crime, therefore, was without motive."[23]

The following day, The New York Times published an article from its Baltimore and New York bureaus, quoting three witnesses. The first was Eratosthemus Charrns, a waiter who said he worked with Schinas at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York and who described Schinas as a "socialist", a "communist", a "radical", and an "atheist". The second was the Greek consul general for New York, Demetrios Botassi, who told the newspaper that Schinas was a "man of education", an "anarchist", and an "atheist", according to "Greeks who knew him well".[36] The same day, The New York Times published a statement from the Greek Minister in London that Schinas was "a victim of alcoholism" and that "the assassination cannot be ascribed to any political motive".[37]

A third article published in the March 20, 1913 New York Times stated that Schinas "is not a madman, but apparently is weak-minded", and that he "led a wretched existence, subsisting almost entirely on milk". According to the article, Schinas visited Volo shortly before the assassination and "declared that in a short time he would succeed in establishing equality; that there would no longer be either rich or poor, and that work which was now accomplished in one hour would be spread out over two." The article stated that Schinas told interrogators he assassinated the king because, "I had to die somehow, as I suffer from neurasthenia, and therefore wished to redeem my life."[2]

On March 21, 1913, The New York Times published Batznoulis's letter to Atlantis generally disputing Botassi's earlier account (but nevertheless describing Schinas as an "anarchist"), along with a statement from Solon Vlasto, editor of Atlantis, endorsing Batznoulis's account and suggesting that the many conflicting stories concerning Schinas's identity may be due to the fact that Schinas is a common surname in Greece and there were likely multiple people named "Aleko Schinas".[4]

Schinas was interviewed in March 1913 and asked the question, "Are you an anarchist?" to which he replied:[9]

No, no! I am not an anarchist, but socialist. I become a socialist, when I was studying medicine in Athens. I do not know how. One becomes a socialist, without realising it, slowly (one step at a time). All people that are good and educated are socialist. The philosophy towards medicine, for me it was the socialism.

One recent scholar has doubted that Schinas was an anarchist or that his actions were an example of propaganda by deed.[38] Writing in 2018, Michael Kemp noted that both "socialism" and "anarchism" were used interchangeably at the time, and that reports of Schinas as having run for political office or invested in a stock market do not support theories that Schinas was either a socialist or an anarchist.[39]

Others have suggested the Schinas was a foreign agent[40] acting on behalf of Austria-Hungary,[3] Bulgaria,[41] Germany,[42] the Ottoman Empire,[43] or Macedonian nationalists.[44] No evidence supporting these theories has emerged.[45] The Norwich Bulletin reported that there were fears of Bulgarian involvement, "but a message received at midnight dispelled such apprehensions by identifying the assassin as a Greek degenerate".[46]

Personal

Some have asserted that the motive for the assassination was revenge for the king's refusal of request for assistance in 1911, or simply that Schinas had lost an inherited fortune in the Greek stock market, was in poor health, and despondent prior to the attack.[2][33] Schinas has been described as an alcoholic,[37] "weak-minded",[2] a "madman",[33] "irresponsible",[46] and of "unstable mind".[47] The Greek government released statements claiming that Schinas was an alcoholic vagrant.[48] The Rural New-Yorker stated: "It is believed that the assassin is mentally unbalanced, and that the crime was not the result of any political conspiracy."[49] Other reports referred to him as "a man of education" or "an educated anarchist".[50]

In a 1913 interview after his arrest, Schinas himself blamed "deliriums" brought on by tuberculosis, saying:[9]

During the night I was waking up, like I was being taken over by madness. I wanted to destroy the world. I wanted to kill everybody, because the whole of society was my enemy. Luck wanted that during this psychological condition to meet the King. I would have killed my own sister if I had met her that day.

More than a year after Schinas's death, The New York Times printed a retrospective article regarding recent political assassinations. The article did not list Schinas among "anarchists who believe in militant tactics", instead describing George I's "murderer" as "a Greek named Aleko Schinas who probably was half demented".[51] A more recent scholar has written that, "Rather than being part of a wider conspiracy, whether political or enacted by a state, Alexandros Schinas may have simply been a sick man (both mentally and physically) seeking an escape from the harsh realities of the early twentieth century."[52] Another describes the gendarmerie's torture of Schinas as producing "a confused confession that mixed anarchist sentiments with a claim that 'he had killed the King because he refused to give him money.'"[53] Some sources have described him simply as "a Greek named Aleko Schinas".[54]

Notes

- Kemp 2018, p. 179: "Little is known of Schinas' life before the assassination."

- The New York Times 1913e.

- Tomai 2012.

- The New York Times 1913f.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178–179.

- Kemp 2018, p. 179–180.

- Kemp 2018, p. 180; The New York Times 1913c.

- Kemp 2018, p. 180; The New York Times 1913f.

- Magrini 1913, p. 185.

- Kemp 2018, p. 180–181.

- Kemp 2018, p. 181–182; The New York Times 1913e.

- Kemp 2018, p. 182; The New York Times 1913e.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; Newton 2014.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; Mattox 2015; Christmas 1914, p. 406.

- Kathimerini 2006: "On March 5, 1913, at the intersection of Vassilissis Olgas and Aghias Triadas streets, Alexandros Schinas, a misfit from Asvestohori, shot and killed King George I. The motive has never been revealed nor has Schinas's testimony in depositions to authorities - a fire broke out on the steamship carrying them to Piraeus. It is reported that in a private conversation with the king's widow, Queen Olga, he stated that he had acted alone, but most historians take the view that he acted on behalf of foreign interests in the Balkans that benefited from the king's murder."

- The New York Times 1913e; Norwich Bulletin 1913

- Kemp 2018, p. 178 states two shots were fired

- Christmas 1914, p. 407; The New York Times 1913f.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; Mattox 2015; Newton 2014; Christmas 1914, p. 407–408.

- The last words of King George I of Greece are a matter of some dispute. The New York Times reported that the king's last words were, "Tomorrow, when I pay my formal visit to the dreadnought Goeben, it is the fact that a German battleship is to honor a Greek King here in Salonika that will fill me with happiness and contentment" (The New York Times 1913). However, George's biographer, Walter Christmas, wrote in the king's biography that "the last words that left the King's lips" were: "Thank God, Christmas can now finish his work with a chapter to the glory of Greece, of the Crown Prince and of the Army." (Christmas 1914, p. 407)

- Ashdown 2011, p. 185; Christmas 1914, p. 406–407.

- Kemp 2018, p. 183; Christmas 1914, p. 407.

- Newton 2014; Christmas 1914, p. 410, 412–416; The New York Times 1913b.

- The New York Times 1913.

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 183: "During his detention Schinas was 'forced to undergo examinations, which failed to elicit any facts to show that other persons were implicated.' One can only imagine what such examinations entailed, but given the popularity of his victim and the oppressive nature of the Greek gendarmerie, it is highly probable that coercion, physical torture and beatings were liberally applied to Schinas by largely conservative and militarized gendarmes of the day. Little is known of Schinas' time in custody other than the suspected abuse that he likely suffered as part of his interrogations."

- Newton 2014, p. 179: "In custody, Schinas initially refused to speak, but was 'forced to undergo examinations'–understood to mean torture–finally producing a confused confession that mixed anarchist sentiments with a claim that 'he had killed the King because he refused to give him money.'"

- The New York Times 1913e

- Magrini 1913, p. 185: "I am now forty-three!"

- The New York Times 1913g.

- Kemp 2018, p. 183; Newton 2014.

- Kathimerini 2006.

- Kemp 2018, p. 183.

- Kemp 2018, p. 181: "The accepted position is that he was a homeless alcoholic with Anarchist tendencies."

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 178: "He is understood and defined as a lone Anarchist actor, and his regicide is assumed to be an example of propaganda of the deed."

- Mattox 2015, p. 22: "His assailant, a Greek named Aleko Schinas, a confirmed Anarchist said to be well eduated, had worked at one time in New York. His principal grievance evidently was the closure by the government of a school of Anarchism he had established in Greece."

- Jensen 2015, p. 121: "While the assassin of King George I of Greece in March 1913 has often been written off as simply a madman, evidence from people who knew Aleko Schinas when he lived in the United State attests to his intelligence and firm anarchist convictions."

- Newton 2014, p. 179: "In custody, Schinas initially refused to speak, but was 'forced to undergo examinations'–understood to mean torture–finally producing a confused confession that mixed anarchist sentiments with a claim that 'he had killed the King because he refused to give him money.'"

- Jensen 2013, p. 21: "In March 1913, an 'educated anarchist' shot to death King George I of Greece."

- New International Encyclopedia 1914, p. 590: "On March 18, 1913, King George of Greece was assassinated at Salonika by an anarchist named Aleko Schinas."

- UPI 1913: "Searching inquiry was set afoot today by the Greek government to determine if possible whether Aleke Schinas was simply an unbalanced anarchist, acting alone, when he shot down King George in a Saloniki street yesterday or whether he was the crafty agent of an organized anarchist band. A rendezvous of anarchists exists at Voto and the ministry heard a report that the plot to kill King George was hatched there. It was rumored here the assassination of the king was but the beginning of an anarchist project to murder the rulers of all the Balkan states, Czar Ferdinand of Bulgaria, King Nicholas of Montenegro, and King Peter of Servia also were said to be marked."

- Kemp 2018, p. 183: "The assassination of King George I is commonly thought to be an example of Anarchist propaganda of the deed (indeed, Schinas is typically referenced as a follower of this philosophy) or the work of a lone madman, motivated by non-political factors. Schinas has been characterized both as an educated and criminally motivated Anarchist and as a hopeless and mentally unbalanced alcoholic."

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 184: "Rather than being part of a wider conspiracy, whether political or enacted by a state, Alexandros Schinas may have simply been a sick man (both mentally and physically) seeking an escape from the harsh realities of the early twentieth century."

- Clogg 2002, p. 241: "In March 1913, while on a visit to Salonica, which had been newly incorporated into the Greek state, he was assassinated by a madman."

- Gallant 2001, p. 129: "In March 1913, King George fell prey to an assassin's bullet. A Greek madman espied the aged monarch out on his daily afternoon walk along the waterfront in Thessaloniki, approached him, and shot him in the back."

- Kemp 2018, p. 184: "Schinas remains an elusive figure and a controversial one. The results of his actions are readily apparent, but what prompted them and, indeed, the details of the man behind them remain ephemeral, drawn as they are from muddled statements provided by multiple sources."

- The New York Times 1913c.

- The New York Times 1913d.

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 180: "[Botassi] described Schinas as a 'man of education and a confirmed anarchist.' This allegation seems somewhat opposed to Schinas' own later protestations and those of others who shared his Socialist beliefs."

- Kemp 2018, p. 183: "Regardless of the motivating factors that lay behind the regicide (which were almost certainly not, as commonly presumed, part of a wider campaign of propaganda of the deed), the consequences to Schinas were severe."

- Kemp 2018, p. 184: "What is clear is that the understanding that Schinas acted as a motivated Anarchist attacker is inherently flawed."

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 180: "It is worth considering, however, that during the nineteenth century the terms 'Socialism' and 'Anarchism' were often used interchangeably. Although there is significant gulf between ideas of remodeling the state and those that aim to remove it altogether, many public figures and press reports of the time ignored this distinction; indeed, both Socialism and Anarchism were seen as a grave social and political threats in the public and media consciousness."

- Kemp 2018, p. 180: "Also according to Botassi, it was during this period that Schinas unsuccessfully stood as a candidate for the office of deputy from Volos for the Greek legislative body. This abortive attempt to join the ranks of the political class did not meet with success, but again, it hardly seems consistent with the actions of a supposed Anarchist radical."

- Kemp 2018, p. 181: "Although an inheritance may well have provided a reason for Schinas to return to Greece following his deportation, it seems unlikely that either a committed Socialist or an avowed Anarchist would invest funds in the unreservedly capitalist stock exchange."

- Kemp 2018, p. 182 (Bulgaria or Ottoman Empire); The National Herald 2017 (Bulgaria, Germany, or Ottoman Empire); Newton 2014, p. 179 (Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, or Germany); Tomai 2012 (Austria-Hungary); Ashdown 2011, p. 185 (Macedonia); Kathimerini 2006 (Bulgaria, Germany, or Ottoman Empire); Gallant 2001, p. 129 (Bulgaria); Christmas 1914, pp. 411–412 (Bulgaria or Ottoman Empire); UPI 1913 (Ottoman Empire)

-

- Gallant 2001, p. 129: "The murderer, Alexandros Schinas, said he killed the King because he would not give him some money, but most Greeks believed that the killer was a Bulgarian agent."

- Christmas 1914, p. 411: "That miserable dipsomaniac was of course only a tool in stronger hands; it was thought that either the Bulgarians or the Young Turks must be behind the atrocious deed, and suspicion fell upon the former."

- Kathimerini 2006: "[Schinas] stated that he had acted alone, but most historians take the view that he acted on behalf of foreign interests in the Balkans that benefited from the king's murder. 'Immediately after the murder, the city was in uproar and rumors offered by Greeks blamed the scapegoats of the time, the Turks and Bulgarians. But more persistent rumors spoke of a German plan to liquidate the pro-English king in order to promote German interests in Greece,' Zafeiris writes. 'One version, considered more likely than the rest, has it that the king was the victim of German diplomacy given that George's policy ran counter to German plans for the Balkans and Eastern Europe. The German rulers themselves wanted the pro-German successor Constantine, who identified with German policy in Greece, at the head of the Greek state.'"

- The National Herald 2017: "Some news reports suggested that Germany, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire may have been behind the assassination."

- Ashdown 2011, p. 185: "However, rumour had it that Skinas was a Macedonian nationalist and that he had been killed by his associates before he could give testimony that would point to their organisation."

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 182: "Another theory is that Schinas, rather than acting of his own volition, was actually acting on behalf of the Turks or the Bulgarians...This conspiracy theory explaining Schinas' actions has several parallels to those pertaining to the assassination of John F. Kennedy (a populist leader with a reduced security detail, supposedly assassinated by mysterious forces acting through a dupe), but its accuracy is questionable. Although many details of Schinas' life are presently unknown (and at the time of the regicide the atmosphere in Thessaloniki was doubtless tense), no evidence that Schinas was acting as an agent for the Ottoman Empire, the Bulgarians, or any other entity has emerged."

- Newton 2014, p. 179: "Conspiracy theories linking Schinas to plotters from Bulgaria, Germany, or Austria-Hungary were never substantiated."

- Ashdown 2011, p. 185: "No evidence was ever found to confirm that story; nor did any nationalist group claim King George's death as their achievement."

- Christmas 1914, p. 412: "I scarcely think there is any necessity to go into the hateful suggestion that one of the Allies of Greece should have sought to promote its ambitions by getting rid of the King. The result of the examination points to the assassin alone. By the myth that immediately came into existence still lives, and it undoubtedly contributed to strengthen the ill-will that was felt for the Bulgarians long before the murder. And the growth of the myth was encouraged by the circumstance that Alexander Skinas avoided further investigations by suicide."

- UPI 1913: "No confirmation of this was forthcoming, though, and nothing developed in Saloniki to indicate the Turks had anything to do with the killing of the Greek king."

- Norwich Bulletin 1913.

- Kemp 2018, p. 181.

- The Times 1913.

- The Rural New-Yorker 1913.

- The Commercial and Financial Chronicle 1913; The New York Times 1913c.

- The New York Times 1914.

- Kemp 2018, p. 184.

- Newton 2014, p. 179.

- Bradstreet 1913.

References

- Ashdown, Dulcie M. (2011-08-26). Royal Murders: Hatred, Revenge and the Seizing of Power. The History Press. ISBN 9780752469195. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bradstreet's Weekly: A Business Digest. Bradstreet Company. 1913-03-22. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.

- Christmas, Walter (1914), King George of Greece, translated by Chater, Arthur G., NY: McBride, Nast & Co, ISBN 9781517258788CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clogg, Richard (2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Commercial and Financial Chronicle. XCVI. National News Service, Incorporated. 1913. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.

- Gallant, Thomas W. (2001). Modern Greece. London: Arnold. p. 129. ISBN 9780340763360.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jensen, Richard Bach (2013). "The first global wave of terrorism and international counter-terrorism". In Hanhimäki, Jussi M.; Blumenau, Bernhard (eds.). An International History of Terrorism: Western and Non-Western Experiences. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 9780415635400. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jensen, Richard Bach (2015-03-27). "Anarchist terrorism and counter-terrorism in Europe and the world, 1878–1934". In Law, Randall D. (ed.). The Routledge History of Terrorism. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 9781317514879. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Four famous targets of assassination in Salonica". Kathimerini. 2006-12-18. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

On March 5[/18], 1913, at the intersection of Vassilissis Olgas and Aghias Triadas streets, Alexandros Schinas, a misfit from Asvestohori, shot and killed King George I. The motive has never been revealed nor has Schinas's testimony in depositions to authorities - a fire broke out on the steamship carrying them to Piraeus. It is reported that in a private conversation with the king's widow, Queen Olga, he stated that he had acted alone, but most historians take the view that he acted on behalf of foreign interests in the Balkans that benefited from the king's murder. «Immediately after the murder, the city was in uproar and rumors offered by Greeks blamed the scapegoats of the time, the Turks and Bulgarians. But more persistent rumors spoke of a German plan to liquidate the pro-English king in order to promote German interests in Greece,» Zafeiris writes. «One version, considered more likely than the rest, has it that the king was the victim of German diplomacy given that George's policy ran counter to German plans for the Balkans and Eastern Europe. The German rulers themselves wanted the pro-German successor Constantine, who identified with German policy in Greece, at the head of the Greek state.» The death of Schinas, who fell or was pushed out of a window at the military headquarters where he was being held, lent force to rumors and speculation about the real cause of the murder.

- Kemp, Michael (2018). "Beneath a White Tower". Bombs, Bullets and Bread: The Politics of Anarchist Terrorism Worldwide, 1866–1926. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 178–186. ISBN 978-1-4766-7101-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Magrini (March 1913), translated by Fragkos, Grigorios, "The King's Assassin Explains Himself to the Journalist Magrini", Aionos, retrieved 2018-12-08CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) as published in Kemp 2018, pp. 184–186

- Mattox, Henry E. (2015-06-08). Chronology of World Terrorism, 1901–2001. McFarland. ISBN 9781476609652. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Assassination of King George – March, 1913". The National Herald. 2017-06-21. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- The New York Times

- a. "King of Greece murdered at Salonika; slayer mad; political results feared" (PDF). The New York Times. Marconi Transaltantic Wireless Telegraph. 1913-03-19. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- b. "Died before reaching hospital" (PDF). The New York Times. 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- c. "The assassin lived here" (PDF). The New York Times. 2013-03-20. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- d. "King's Murderer is Educated Anarchist" (PDF). The New York Times. Marconi Transatlantic Wireless Telegraph. 1913-03-20. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- e. "King's murderer is educated anarchist (part 2, Salonika)" (PDF). The New York Times. 1913-03-20. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- f. "Salonika (untitled)" (PDF). The New York Times. 1913-03-21. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- g. "King's slayer a suicide" (PDF). The New York Times. 1913-05-07. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- h. "Many rulers fell at fanatics' hands" (PDF). The New York Times. 1914-06-29. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- Newton, Michael (2014-04-17). Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. Santa Barbara, CA, USA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610692861. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "King shot through heart". Norwich Bulletin. XV (67). 1913-03-19. ISSN 2377-5866. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- "Propaganda of the Deed". New International Encyclopedia. Dodd, Mead. 1914. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.

- "Foreign (untitled)". The Rural New-Yorker. 72 (4196). Rural Publishing Company. 1913-03-29. p. 473. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.

- Schurman (1913-03-18). "The American Minister to the Secretary of State". Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, With the Address of the President to Congress December 2, 1913. Office of the Historian, U.S. Dept. of State. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09.

Reports that King George was shot and killed this afternoon at Saloniki. While walking with an aide de camp a Greek socialist shot him through the heart from behind a wall.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "King of Hellenes murdered". The Times (London). 1913-03-19. p. 6.

- Tomai, Fotini (2012-10-21). "Ο Γεώργιος Α' και ο δολοφόνος του - νέα - Το Βήμα Online". Βήμα Online (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2018-12-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Anarchists plot to murder all Balkan kings, Greece hears". United Press International. 1913-03-19. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2018-12-09.