Alcestis

Alcestis (/ælˈsɛstɪs/; Ancient Greek: Ἄλκηστις, Álkēstis) or Alceste, was a princess in Greek mythology, known for her love of her husband. Her life story was told by pseudo-Apollodorus in his Bibliotheca,[1] and a version of her death and return from the dead was also popularized in Euripides's tragedy Alcestis.

Family

Alcestis was the fairest among the daughters of Pelias, king of Iolcus, and either Anaxibia or Phylomache. She was sister to Acastus, Pisidice, Pelopia and Hippothoe.[2] Alcestis was the wife of Admetus by whom she bore a son, Eumelus, a participant in the siege of Troy, and a daughter, Perimele.[3]

Mythology

Many suitors appeared before King Pelias and tried to woo Alcestis when she came of age to marry. It was declared by her father that she would marry the first man to yoke a lion and a boar (or a bear in some cases) to a chariot. The man who would do this, King Admetus, was helped by Apollo, who had been banished from Olympus for one year to serve as a shepherd to Admetus. With Apollo's help, Admetus completed the challenge set by King Pelias, and was allowed to marry Alcestis. But in a sacrifice after the wedding, Admetus forgot to make the required offering to Artemis, therefore when he opened the marriage chamber he found his bed full of coiled snakes.[4] Admetus interpreted it a portent of an early death.[5]

Apollo again helped the newlywed king, this time by making the Fates drunk, extracting from them a promise that if anyone would want to die instead of Admetus, they would allow it. And when the day of his death came near, no one volunteered, not even his elderly parents, but Alcestis stepped forth to die in his stead. Shortly after fighting with Thanatos, Heracles rescued Alcestis from the underworld as a token of appreciation for Admetus' hospitality.[6] In some accounts Persephone, 'the Maiden', sent her up again. But when she comes back alive she is mute. She chooses not to speak.

Appearance in other works

- Milton's famous sonnet, "Methought I Saw My Late Espoused Saint", c. 1650, alludes to the myth, with the speaker of the poem dreaming of his dead wife being brought to him "like Alcestis".

- Lully wrote an opera, first performed in 1674, based on the story.

- Händel wrote a 1750 masque, or semi-opera, based on this myth.

- Gluck in 1767 wrote a significant reform opera on the story.

- Schweitzer composed an opera Alceste to a libretto by Wieland, premiered in 1773 in Weimar, as a milestone of German opera.[7]

- In his poem "Past Ruin'd Ilion", English writer and poet Walter Savage Landor (1775–1864) wrote the line "Alcestis rises from the shades" as having a double meaning, evoking her rise from Hades while demonstrating the ability of enduring poetry to give her vitality, drawing her into the light from the shadows of historical oblivion.

- Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a poem "Alkestis".

- H. P. Lovecraft and Sonia Greene collaborated on a play called Alcestis (however, Lovecraft scholar S. T. Joshi thinks it is entirely Greene's work).[8]

- Thornton Wilder wrote A Life in the Sun (1955) based on Euripides' play, later producing an operatic version called The Alcestiad (1962).

- The American choreographer Martha Graham created a ballet entitled Alcestis in 1960.

- In the animated Disney film Hercules, the background story of the Megara character also alludes to Alcestis. As Hades tells it, Megara sells her soul for her lover, who does not honor the sacrifice and very soon gives his heart to some other girl.

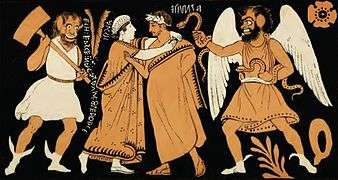

Gallery

Scenes from the myth of Admetus and Alcestis. Marble, sarcophagus of C. Junius Euphodus and Metilla Acte, 161–170 CE.

Scenes from the myth of Admetus and Alcestis. Marble, sarcophagus of C. Junius Euphodus and Metilla Acte, 161–170 CE. The Farewell of Admetus and Alcestis by George Dennis (1848)

The Farewell of Admetus and Alcestis by George Dennis (1848) Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis by Frederic Lord Leighton, England (c. 1869-1871)

Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis by Frederic Lord Leighton, England (c. 1869-1871) The Death of Alcestis by Angelica Kauffman.

The Death of Alcestis by Angelica Kauffman. Admetus beweint Alkeste by Johann Heinrich Tischbein (circa 1780)

Admetus beweint Alkeste by Johann Heinrich Tischbein (circa 1780) Herkules entreißt Alkestis dem Totengott Thanatos und führt sie dem Admetus zu by Johann Heinrich Tischbein (circa 1780)

Herkules entreißt Alkestis dem Totengott Thanatos und führt sie dem Admetus zu by Johann Heinrich Tischbein (circa 1780) Alceste mourante by Jean-François Pierre Peyron (1785)

Alceste mourante by Jean-François Pierre Peyron (1785) Alcestis and Admetus, ancient Roman fresco (45-79 d.C.) from the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii, Italy

Alcestis and Admetus, ancient Roman fresco (45-79 d.C.) from the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii, Italy- Alcestis and Admetus, ancient Roman fresco (45-79 d.C.) by Stefano Bolognini from the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii, Italy

Alkeste se pro svého manžela Adméta zasvěcuje bohům podsvětí by Heinrich Füger (1810s)

Alkeste se pro svého manžela Adméta zasvěcuje bohům podsvětí by Heinrich Füger (1810s)

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alcestis. |

- [[Bibliotheca (Pseudo-Apollodorus |Pseudo-Apollodorus)

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.9.10

- Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphosis 23

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.9.15

- Roman, L., & Roman, M. (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman mythology., p. 54, at Google Books

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2.6.2

- Lawrence, Richard (July 2008). "Schweitzer, A Alceste". Gramophone. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "The Contributions within Lovecraft's Collaborations"

References

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Alcestis. |

- Antoninus Liberalis, The Metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis translated by Francis Celoria (Routledge 1992). Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Cotterell, Arthur, and Rachel Storm. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology. Hermes House. ISBN 978-0-681-03218-7.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, The Library with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

External links

- "Alcestis"—a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke