Aftermath of the Cuban Revolution

During its first decade in power, the Castro government introduced a wide range of progressive social reforms. Laws were introduced to provide equality for black Cubans and greater rights for women, and there were attempts to improve communications, medical facilities, health, housing, and education. In addition, there were touring cinemas, art exhibitions, concerts, and theatres. By the end of the 1960s, all Cuban children were receiving some education (compared with less than half before 1959), unemployment and corruption were reduced, and great improvements were made in hygiene and sanitation.[1] Fidel dedicated many of his years to the equality among Afro-Cubans and the wealthy white people of Cuba. His anti-discrimination legislation was his first and major attempt to give equality to the people of Cuba. His many reforms (healthcare, education, and equality) gave opportunities to those Afro-Cubans who lived in poverty because of the racial discrimination in Cuba.[2]

The equal right of all citizens to health, education, work, food, security, culture, science, and wellbeing – that is, the same rights we proclaimed when we began our struggle, in addition to those which emerge from our dreams of justice and equality for all inhabitants of our world – is what I wish for all.

— Fidel Castro[3]

| Part of the Cold War | |

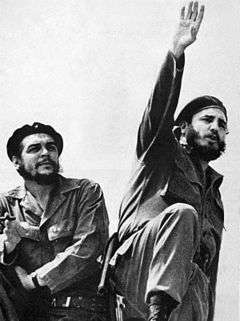

Che Guevara (left) and Fidel Castro (right) in 1961. | |

| Date | 1960s |

|---|---|

| Location | Cuba |

| Outcome | Series of events including... |

Background

The Cuban Revolution (Spanish: Revolución cubana) was a guerrilla campaign by Fidel Castro's revolutionary 26th of July Movement and others against the dictatorship of Cuban President Fulgencio Batista. The revolution started in July 1953,[4] and continued to varying degrees until the rebels finally ousted Batista on 31 December 1958, creating a new revolutionary government.[5]

After learning of Batista's flight the rebels immediately started negotiations to take over Santiago de Cuba. On 2 January, Cuban Colonel Rubido, ordered his soldiers to stand down, and the rebels took the city. The rebel forces under Guevara and Cienfuegos entered Havana at about the same time. The rebels met no opposition on their way from Santa Clara to Havana. Castro arrived in Havana on 8 January after a victory march. His first choice of president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, took office on 3 January.[6]

Events after victory

Our revolution is endangering all American possessions in Latin America. We are telling these countries to make their own revolution.

— Che Guevara, October 1962[7]

Media appearances

On 11 January 1959 Ed Sullivan would interview Fidel Castro in Matanzas and broadcast it on The Ed Sullivan Show. In the interview Ed Sullivan refers to the Castro and other rebels as "a wonderful group of revolutionary youngsters" and point out their admiration for Catholicism. Fidel Castro would deny the rebels affiliation with communism. Hours after the interview Fidel Castro would ride on captured tanks into the capital in Havana.[8]

On 15 April 1959, Castro began an 11-day visit to the United States, at the invitation of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.[9] He said during his visit: "I know the world thinks of us, we are Communists, and of course I have said very clear that we are not Communists; very clear."[10]

Revolutionary tribunals

Hundreds of Batista-era agents, policemen and soldiers were put on public trial, accused of human rights abuses, war crimes, murder, and torture. About 200 of the accused people were convicted of political crimes by revolutionary tribunals and then executed by firing squad; others received long sentences of imprisonment. A notable example of revolutionary justice occurred after the capture of Santiago, where Raúl Castro directed the execution of more than seventy Batista POWs.[11] For his part in taking Havana, Che Guevara was appointed supreme prosecutor in La Cabaña Fortress. This was part of a large-scale attempt by Fidel Castro to cleanse the security forces of Batista loyalists and potential non-Communist opponents (including high-ranking rebels such as Pedro Luis Díaz Lanz and Huber Matos) of the new revolutionary government. Though many were killed or imprisoned, others were dismissed from the army and police without prosecution, and some high-ranking officials of the Batista administration were exiled as military attachés.[11] The trials did follow due process.[12]

Reforms

Racial integration campaign

Starting in March 1959 Fidel Castro announced in a speech he would attempt to end racial discrimination in Cuban society. He detailed a plan to bring black and white Cubans together in shared schools and other institutions, via equal opportunity. In a later televised discussion Castro claimed his plans were mostly to improve economic conditions for black Cubans and that he is not encouraging total social integration. Social clubs were to be totally integrated, private beaches opened, and schools totally nationalized. Revolutionary leaders would also decry to the white supremacist terrorism of the U.S. South in an attempt to gain a moral high ground and defame Cuban exiles living in the United States. When discussing fears of unruly black people in Cuba, Castro stated "“blacks should be more respectful than before because they understood that the revolution was working to eliminate discrimination".[13]

Private schools that once had majority white student bodies were now nationalized and faced an influx of new black and mulatto students. Social clubs were told to integrate as early as January 1959. White and black social clubs began to dissolve. Racism became branded as counterrevolutionary and critics of the government were often branded as racists.[13]

Some white Cubans were fearful of integration, while some black Cubans were fearful of the closing of black social clubs and its affects on Afro-Cuban cultural life.[13]

Land reform and United States relations

Fidel Castro visited the United States in April 1959 in hopes of securing U.S. aid for Cuba. While there he openly spoke of plans to nationalize Cuban lands and at the United Nations he declared Cuba was neutral in the Cold War.[14]

According to geographer and Cuban Comandante Antonio Núñez Jiménez, 75% of Cuba's best arable land was owned by foreign individuals or foreign (mostly American) companies at the time of the revolution. One of the first policies of the newly formed Cuban government was eliminating illiteracy and implementing land reforms. Land reform efforts helped to raise living standards by subdividing larger holdings into cooperatives. Comandante Sori Marin, who was nominally in charge of land reform, objected and fled, but was eventually executed when he returned to Cuba with arms and explosives, intending to overthrow the Castro government.[15][16]

The United States was already suspicious of Fidel Castro after he enacted the Agrarian Reform Law banning foreigners from owning land and his appointment of communist Nuñez Jimenez as head of the reform program. U.S. President Eisenhower refused any aggressive action against Cuba knowing it would push Cuba towards an alliance with the Soviet Union in the Cold War.[14]

In 1960 Fidel Castro nationalized U.S. oil refineries after accusing Cuban exiles of flying bombing missions over Cuba. The U.S. then cut all sugar trade with Cuba, later Castro would forge a sugar trade deal with the Soviet Union.[14]

Cuba-United States relations were heavily strained after the explosion of a French vessel, the La Coubre, in Havana harbor in March 1960. The ship carried weapons purchased from Belgium, and the cause of the explosion was never determined, but Castro publicly insinuated that the U.S. government was guilty of sabotage. He ended this speech with "¡Patria o Muerte!" ("Fatherland or Death"), a proclamation that he made much use of in ensuing years.[17]

Shortly after taking power, Castro also founded a revolutionary militia to expand his power base among the former rebels and the supportive population. Castro also founded the informant Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) in late September 1960. Local CDRs were tasked with keeping "vigilance against counter-revolutionary activity", keeping a detailed record of each neighborhood's inhabitants' spending habits, level of contact with foreigners, work and education history, and any "suspicious" behavior.[18] Among the increasingly persecuted groups were homosexual men.[19]

By the end of 1960, the revolutionary government had nationalized more than $25 billion worth of private property owned by Cubans.[20] The Castro government formally nationalized all foreign-owned property, particularly American holdings, in the nation on 6 August 1960.[21]

In 1961, the Cuban government nationalized all property held by religious organizations, including the dominant Roman Catholic Church. Hundreds of members of the church, including a bishop, were permanently expelled from the nation, as the new Cuban government declared itself officially atheist. Education also saw significant changes – private schools were banned and the progressively socialist state assumed greater responsibility for children.[22] The Cuban government also began to expropriate from mafia leaders and taking millions in cash. Before Meyer Lansky fled Cuba, he was said to be worth an estimated $20M ($163,685,121 in 2016, accounting for inflation). When he died in 1983, his family was shocked to find out that his estate was worth about $57,000. Before he died, Lansky said that Cuba "ruined" him.[23]

In July 1961, the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (IRO) was formed by the merger of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement, the People's Socialist Party led by Blas Roca, and the Revolutionary Directorate of 13 March led by Faure Chomón.[24] On 26 March 1962, the IRO became the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution (PURSC) which, in turn, became the modern Communist Party of Cuba on 3 October 1965, with Castro as First Secretary. Castro remained the ruler of Cuba, first as Prime Minister and, from 1976, as President, until his retirement in February 20, 2008.[25] His brother Raúl officially replaced him as President later that same month.[26]

Opposition to Fidel Castro

Escambray rebellion

In the wake of the revolution, thousands of disaffected anti-Batista rebels, former Batista supporters, and campesinos (peasants) fled to Cuba's Las Villas province, where an anticommunist underground had been forming since early 1960. Operating out of the Escambray Mountains, these counterrevolutionary rebels, also known as Alzados, made a number of unsuccessful attempts to overthrow the Cuban government, including the abortive, United States-backed Bay of Pigs Invasion of 1961.[27]

United States intervention

In January 1961 the U.S. cut off diplomatic relations with Cuba. The U.S. feared Soviet influence in Cuba and backed the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion of April 1961. By December 1961 Fidel Castro for the first time openly expressed his communist sympathies. Castro's fears of another invasion and his new Soviet allies influenced his decision to put nuclear missiles in Cuba, triggering the Cuban Missile Crisis.[14]

In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the United States promised not to invade Cuba in the future; in compliance with this agreement, the U.S. withdrew all support from the Alzados, effectively crippling the resource-starved resistance.[28] The counterrevolutionary conflict, known abroad as the Escambray Rebellion, lasted until about 1965, and has since been branded the War Against the Bandits by the Cuban government.[28]

Luis Posada and CORU are widely considered responsible for the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner that killed 73 people.[29][30]

Cuban exile

Between 1959 and 1980, an estimated 500,000 Cubans left the island for the United States, for both political and economic reasons; 125,000 left in 1980 alone, when the Cuban government briefly permitted any Cubans who wished to leave to do so.[31] By 2010, the Cuban American community numbered over 1.9 million, 67% of whom lived in the state of Florida.[32] As a voting bloc, Cuban Americans have traditionally been strongly opposed to ending the U.S. embargo of Cuba, but in recent years there has been growing support for diplomatic engagement among the younger generations.[33]

New racial policies

Castro's government was entirely based on his ideologies of equality and fair measures for the people of Cuba. After he considered to have done everything in his power toward equality, he passed a legislation that counter-attacked his past anti-discrimination legislation. This law made it illegal to even mention discrimination or the topic of equality.[2]

References

- Mastering Modern World History by Norman Lowe, second edition.

- Espina, Rodrigo (March 2006). "Raza y desigualdad en Cuba actual" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2017.

- "Fidel Castro Quotes".

- Faria, Miguel A., Jr. (27 July 2004). "Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement". Newsmax Media. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Cuba Marks 50 Years Since 'Triumphant Revolution'" Archived 27 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Jason Beaubien. NPR. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- Thomas (1998), pp. 691–93

- "Attack us at your Peril, Cocky Cuba Warns US" Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Henry Brandon. The Sunday Times. 28 October 1962. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "When Fidel Castro Charmed the United States". Smithsonian.com.

- Glass, Andrew (15 April 2013). "Fidel Castro visits the U.S., April 15, 1959". Politico. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Cuban Revolution". 1959 Year in Review. United Press International. 1959. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Clark (1992), pp. 53–70

- Chase, Michelle (2010). "The Trials". In Greg Grandin; Joseph Gilbert (eds.). A Century of Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 163–98. ISBN 978-0822347378. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- Benson, Devyn (2012). "Owning the Revolution: Race, Revolution, and Politics from Havana to Miami, 1959–1963" (PDF).

- Stanley, John. "What impact did the Cuban Revolution have on the Cold War?" (PDF).

- Font (1995), pp. 80–81

- Lazo (1968), pp. 288

- Bourne 1986, pp. 201–202

- Clark (1992), pp. 131–158

- Young, Allen (1982). Gays under the Cuban revolution. Grey Fox Press. ISBN 0-912516-61-5.

- Lazo, Mario (1970). American Policy Failures in Cuba – Dagger in the Heart. Twin Circle Publishing Co.: New York. pp. 198–200, 204. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 68-31632.

- Gary B. Nash, Julie Roy Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, Allan M. Winkler, Charlene Mires and Carla Gardina Pestana. The American People, Concise Edition: Creating a Nation and a Society, Combined Volume (6th edition, 2007). New York: Longman.

- Faria (2002), pp. 215–28

- "Fidel Castro a mixed legacy that includes fighting the mafia". 26 November 2016. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Kantor, Myles B. (14 June 2002). "Interview With Dr. Miguel Faria (Part I)". Newsmax Media. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Fidel Castro Resigns as Cuba's President". New York Times. 20 February 2008. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Raúl Castro becomes Cuban president". New York Times. 24 February 2008. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Ahead Of Bay Of Pigs, Fears Of Communism". NPR. 17 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "Cuba: Intelligence and the Bay of Pigs". Stanford University. 26 September 2002. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- Bardach, Ann Louis; Rohter, Larry (July 13, 1998). "A Bomber's Tale: Decades of Intrigue" Archived 3 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. The New York Times Company.

- Lettieri, Mike (June 1, 2007). "Posada Carriles, Bush's Child of Scorn". Washington Report on the Hemisphere. 27 (7/8).

- "Cuban Exile Community". LatinAmericanStudies.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "Hispanics of Cuban Origin in the United States, 2010". Pew Research. 27 June 2012. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "Latino millennials want to end Cuba embargo". CNN. 24 October 2012. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.