Abolition of the Caliphate

The Ottoman Caliphate, the world's last widely recognized caliphate, was abolished on 3 March 1924 (26 Rajab 1342 AH) by decree of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey as one of the reforms following the replacement of the Ottoman Empire with the Republic of Turkey under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[1] Abdülmecid II was deposed as the last Ottoman Caliph, as was Mustafa Sabri as the last Ottoman Shaykh al-Islām.

The caliph was nominally the supreme religious and political leader of all Muslims across the world.[2] In the years prior to the abolition, during the ongoing Turkish Revolution, the uncertain future of the caliphate provoked strong reactions among the worldwide Sunni Islam community.[3] The potential abolition of the caliphate had been actively opposed by the Indian-based Khilafat Movement,[1] and generated heated debate throughout the Muslim world.[4] The 1924 abolition came less than 18 months after the abolition of the Ottoman sultanate, prior to which the Ottoman sultan was ex officio caliph.

Atatürk reportedly offered the caliphate to Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi, on the condition that he reside outside Turkey; Senussi declined the offer and confirmed his support for Abdülmecid.[5] At least thirteen different candidates were proposed for the caliphate in subsequent years, but none was able to gain a consensus for the candidacy across the Islamic world.[6][7] Candidates included Abdülmecid II, his predecessor Mehmed VI, King Hussein of the Hejaz, King Yusef of Morocco, Prince Amanullah Khan of Afghanistan, Imam Yahya of Yemen, and King Fuad I of Egypt.[6] Unsuccessful "caliphate conferences" were held in Indonesia in 1924,[7] in 1926 in Cairo, and in 1931 in Jerusalem.[6][7]

Ottoman pan-Islamism

In the late 19th century, Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II launched his pan-Islamist program in a bid to protect the Ottoman Empire from Western attack and dismemberment, and to crush the democratic opposition at home.

He sent an emissary, Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī, to India in the late 19th century. The cause of the Ottoman monarch evoked religious passion and sympathy amongst Indian Muslims. A large number of Muslim religious leaders began working to spread awareness and develop Muslim participation on behalf of the caliphate; of these, Maulana Mehmud Hasan attempted to organize a national war of independence against the British Raj with support from the Ottoman Empire.[8]

End of the sultanate

Following the Ottoman defeat in World War I, the Ottoman sultan under Allied direction attempted to suppress nationalist movements, and secured an official fatwa from the Sheikh ul-Islam declaring these to be un-Islamic. But the nationalists steadily gained momentum and began to enjoy widespread support. Many sensed that the nation was ripe for revolution. In an effort to neutralize this threat, the sultan agreed to hold elections, with the hope of placating and co-opting the nationalists. To his dismay, nationalist groups swept the polls, prompting the Allied Powers to dissolve the General Assembly of the Ottoman Empire in April 1920.[9]

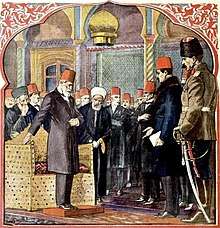

At the end of the Turkish War of Independence, the Turkish National Movement's Grand National Assembly voted to separate the caliphate from the sultanate and abolished the latter on 1 November 1922.[10] Initially, the National Assembly seemed willing to allow a place for the caliphate in the new regime and Mustafa Kemal did not dare to abolish the caliphate outright, as it still commanded a considerable degree of support from the common people. The caliphate was symbolically vested in the House of Osman.[11] On 19 November 1922, the Crown Prince Abdülmecid was elected caliph by the Turkish National Assembly at Ankara.[10] He established himself in Istanbul (at those time Constantinople) on 24 November 1922. But the position had been stripped of any authority, and Abdülmecid's purely ceremonial reign would be short-lived.[12]

When Abdülmecid was declared caliph, Kemal refused to allow the traditional Ottoman ceremony to take place, bluntly declaring:

The Caliph has no power or position except as a nominal figurehead.[13]

In response to Abdülmecid's petition for an increase in his allowance, Kemal wrote:

Your office, the Caliphate, is nothing more than a historic relic. It has no justification for existence. It is a piece of impertinence that you should dare write to any of my secretaries![13]

On 29 October 1923, the National Assembly declared Turkey a republic, and proclaimed Ankara its new capital. After over 600 years, the Ottoman Empire had officially ceased to exist.[10]

1924 abolition

Two Indian brothers, Maulana Mohammad Ali and Maulana Shaukat Ali, leaders of the Indian-based Khilafat Movement, distributed pamphlets calling upon the Turkish people to preserve the Ottoman Caliphate for the sake of Islam. On 24 November 1923, Syed Ameer Ali and Aga Khan III sent a letter to İsmet İnönü on behalf of the movement.[14] Under Turkey's new nationalist government, however, this was construed as foreign intervention; any form of foreign intervention was labelled an insult to Turkish sovereignty and worse, a threat to state security. Kemal promptly seized his chance. On his initiative, the National Assembly abolished the caliphate on March 3, 1924. Abdülmecid was sent into exile along with the remaining members of the Ottoman House.[15]

Aftermath

In Egypt, debate focused on a controversial book by Ali Abdel Raziq which argued for secular government and against a caliphate.[16]

Today, two frameworks for pan-Islamic coordination exist: the Muslim World League and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, both of which were founded in the 1960s.[17]

The most active group that exists to re-establish the caliphate is Hizb ut-Tahrir, founded in 1953 as a political organization in then Jordanian-controlled Jerusalem by Taqiuddin al-Nabhani, an Islamic scholar and appeals court judge from Haifa.[18] This organization has spread to more than 50 countries, and grown to a membership estimated to be between "tens of thousands"[19] to "about one million".[20]

References

- Brown 2011, p. 260.

- Özcan 1997, pp. 45–52.

- Nafi 2012, p. 47.

- Nafi 2012, p. 31.

- Özoğlu 2011, p. 5; Özoğlu quotes 867.00/1801: Mark Lambert Bristol on 19 August 1924.

- Ardıç 2012, p. 85.

- Pankhurst 2013, p. 59.

- Özcan 1997, pp. 89–111.

- Enayat & ʻInāyat 2005, pp. 52–53.

- Nafi 2016, p. 184.

- Dahlan 2018, p. 133.

- Enayat & ʻInāyat 2005, p. 53.

- Armstrong 1933, p. 243.

- Nafi 2016, pp. 185–186.

- Nafi 2016, p. 183.

- Nafi 2016, p. 189.

- Nafi 2016, pp. 190–191.

- "Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami (Islamic Party of Liberation)". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Filiu, Jean-Pierre (June 2008). "Hizb ut-Tahrir and the fantasy of the caliphate". Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Malik, Shiv (13 September 2004). "For Allah and the caliphate". New Statesman. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

Bibliography

- Nafi, Basheer (2016). "The Abolition of the caliphate: causes and consequences". The Different aspects of Islamic culture, v. 6, pt. I: Islam in the World today, Retrospective of the evolution of Islam and the Muslim world. UNESCO. pp. 183–192.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Daniel W. (24 August 2011). A New Introduction to Islam. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5772-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Hugh (11 October 2016). Caliphate: The History of an Idea. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-09439-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Antony (19 July 2011). History of Islamic Political Thought. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8878-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oliver-Dee, Sean (13 August 2009). The Caliphate Question: The British Government and Islamic Governance. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-3603-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nafi, Basheer (11 December 2012). "The Abolition of the Caliphate in Historical Context". In Al-Rasheed; Kersten; Shterin (eds.). Demystifying the Caliphate: Historical Memory and Contemporary Contexts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-932795-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Thomas W. (18 November 2016). The Caliphate. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-315-44322-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ardıç, Nurullah (2012). Islam and the Politics of Secularism: The Caliphate and Middle Eastern Modernization in the Early 20th Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-67166-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Teitelbaum, Joshua (2000). ""Taking Back" the Caliphate: Sharīf Ḥusayn Ibn ʿAlī, Mustafa Kemal and the Ottoman Caliphate". Die Welt des Islams. 40 (3): 412–424. doi:10.1163/1570060001505343. JSTOR 1571258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kedourie, Elie (1963). "Egypt and the Caliphate 1915-1946". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 3/4 (3/4): 208–248. JSTOR 25202646.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Özoğlu, Hakan (2011). From Caliphate to Secular State: Power Struggle in the Early Turkish Republic. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37956-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guida, Michelangelo (2008). "Seyyid Bey and the Abolition of the Caliphate". Middle Eastern Studies. 44 (2): 275–289. doi:10.1080/00263200701874917. JSTOR 40262571.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dahlan, Malik (1 August 2018). The Hijaz: The First Islamic State. Oxford University Press. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-0-19-093501-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pankhurst, Reza (12 April 2013). The Inevitable Caliphate?: A History of the Struggle for Global Islamic Union, 1924 to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-025732-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Armstrong, Harold Courtenay (1933). Gray Wolf, Mustafa Kemal: An Intimate Study of a Dictator. Minton, Balch & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Enayat, Hamid; ʻInāyat, Ḥamīd (24 June 2005). "The Crisis Over The Caliphate". Modern Islamic Political Thought. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-465-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Özcan, Azmi (1997). Pan-Islamism: Indian Muslims, the Ottomans and Britain, 1877–1924. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10632-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abolition of the Caliphate. |