3D printing

3D printing, or additive manufacturing, is the construction of a three-dimensional object from a CAD model or a digital 3D model.[1] The term "3D printing" can refer to a variety of processes in which material is joined or solidified under computer control to create a three-dimensional object,[2] with material being added together (such as liquid molecules or powder grains being fused together), typically layer by layer.

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of printing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the 1990s, 3D printing techniques were considered suitable only for the production of functional or aesthetic prototypes, and a more appropriate term for it at the time was rapid prototyping.[3] As of 2019, the precision, repeatability, and material range of 3D printing has increased to the point that some 3D printing processes are considered viable as an industrial-production technology, whereby the term additive manufacturing can be used synonymously with 3D printing. One of the key advantages of 3D printing is the ability to produce very complex shapes or geometries that would be otherwise impossible to construct by hand, including hollow parts or parts with internal truss structures to reduce weight. Fused deposition modeling, or FDM, is the most common 3D printing process in use as of 2018.[4]

Terminology

The umbrella term additive manufacturing (AM) gained popularity in the 2000s,[5] inspired by the theme of material being added together (in any of various ways). In contrast, the term subtractive manufacturing appeared as a retronym for the large family of machining processes with material removal as their common process. The term 3D printing still referred only to the polymer technologies in most minds, and the term AM was more likely to be used in metalworking and end use part production contexts than among polymer, ink-jet, or stereo lithography enthusiasts.

By early 2010s, the terms 3D printing and additive manufacturing evolved senses in which they were alternate umbrella terms for additive technologies, one being used in popular language by consumer-maker communities and the media, and the other used more formally by industrial end-use part producers, machine manufacturers, and global technical standards organizations. Until recently, the term 3D printing has been associated with machines low in price or in capability.[6] 3D printing and additive manufacturing reflect that the technologies share the theme of material addition or joining throughout a 3D work envelope under automated control. Peter Zelinski, the editor-in-chief of Additive Manufacturing magazine, pointed out in 2017 that the terms are still often synonymous in casual usage[7] but some manufacturing industry experts are trying to make a distinction whereby Additive Manufacturing comprises 3D printing plus other technologies or other aspects of a manufacturing process.[7]

Other terms that have been used as synonyms or hypernyms have included desktop manufacturing, rapid manufacturing (as the logical production-level successor to rapid prototyping), and on-demand manufacturing (which echoes on-demand printing in the 2D sense of printing). Such application of the adjectives rapid and on-demand to the noun manufacturing was novel in the 2000s reveals the prevailing mental model of the long industrial era in which almost all production manufacturing involved long lead times for laborious tooling development. Today, the term subtractive has not replaced the term machining, instead complementing it when a term that covers any removal method is needed. Agile tooling is the use of modular means to design tooling that is produced by additive manufacturing or 3D printing methods to enable quick prototyping and responses to tooling and fixture needs. Agile tooling uses a cost-effective and high-quality method to quickly respond to customer and market needs, and it can be used in hydro-forming, stamping, injection molding and other manufacturing processes.

History

1970s

In 1974, David E. H. Jones laid out the concept of 3D printing in his regular column Ariadne in the journal New Scientist.[8][9]

1980s

Early additive manufacturing equipment and materials were developed in the 1980s.[10] In 1981, Hideo Kodama of Nagoya Municipal Industrial Research Institute invented two additive methods for fabricating three-dimensional plastic models with photo-hardening thermoset polymer, where the UV exposure area is controlled by a mask pattern or a scanning fiber transmitter.[11][12]

On July 2, 1984, American entrepreneur Bill Masters filed a patent for his Computer Automated Manufacturing Process and System (US 4665492).[13] This filing is on record at the USPTO as the first 3D printing patent in history; it was the first of three patents belonging to Masters that laid the foundation for the 3D printing systems used today.[14][15]

On 16 July 1984, Alain Le Méhauté, Olivier de Witte, and Jean Claude André filed their patent for the stereolithography process.[16] The application of the French inventors was abandoned by the French General Electric Company (now Alcatel-Alsthom) and CILAS (The Laser Consortium).[17] The claimed reason was "for lack of business perspective".[18]

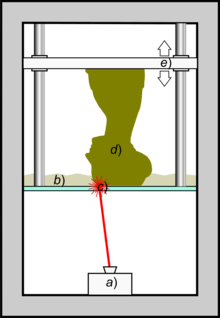

Three weeks later in 1984, Chuck Hull of 3D Systems Corporation[19] filed his own patent for a stereolithography fabrication system, in which layers are added by curing photopolymers with ultraviolet light lasers. Hull defined the process as a "system for generating three-dimensional objects by creating a cross-sectional pattern of the object to be formed,".[20][21] Hull's contribution was the STL (Stereolithography) file format and the digital slicing and infill strategies common to many processes today.

In 1986, Charles "Chuck" Hull was granted a patent for his system, and his company, 3D Systems Corporation released the first commercial 3D printer, the SLA-1.[22]

The technology used by most 3D printers to date—especially hobbyist and consumer-oriented models—is fused deposition modeling, a special application of plastic extrusion, developed in 1988 by S. Scott Crump and commercialized by his company Stratasys, which marketed its first FDM machine in 1992.

1990s

AM processes for metal sintering or melting (such as selective laser sintering, direct metal laser sintering, and selective laser melting) usually went by their own individual names in the 1980s and 1990s. At the time, all metalworking was done by processes that are now called non-additive (casting, fabrication, stamping, and machining); although plenty of automation was applied to those technologies (such as by robot welding and CNC), the idea of a tool or head moving through a 3D work envelope transforming a mass of raw material into a desired shape with a toolpath was associated in metalworking only with processes that removed metal (rather than adding it), such as CNC milling, CNC EDM, and many others. But the automated techniques that added metal, which would later be called additive manufacturing, were beginning to challenge that assumption. By the mid-1990s, new techniques for material deposition were developed at Stanford and Carnegie Mellon University, including microcasting[23] and sprayed materials.[24] Sacrificial and support materials had also become more common, enabling new object geometries.[25]

The term 3D printing originally referred to a powder bed process employing standard and custom inkjet print heads, developed at MIT by Emanuel Sachs in 1993 and commercialized by Soligen Technologies, Extrude Hone Corporation, and Z Corporation.

The year 1993 also saw the start of a company called Solidscape, introducing a high-precision polymer jet fabrication system with soluble support structures, (categorized as a "dot-on-dot" technique).

In 1995 the Fraunhofer Society developed the selective laser melting process.

2000s

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) printing process patents expired in 2009.[26]

2010s

As the various additive processes matured, it became clear that soon metal removal would no longer be the only metalworking process done through a tool or head moving through a 3D work envelope, transforming a mass of raw material into a desired shape layer by layer. The 2010s were the first decade in which metal end use parts such as engine brackets[27] and large nuts[28] would be grown (either before or instead of machining) in job production rather than obligately being machined from bar stock or plate. It is still the case that casting, fabrication, stamping, and machining are more prevalent than additive manufacturing in metalworking, but AM is now beginning to make significant inroads, and with the advantages of design for additive manufacturing, it is clear to engineers that much more is to come.

As technology matured, several authors had begun to speculate that 3D printing could aid in sustainable development in the developing world.[29]

In 2012, Filabot developed a system for closing the loop[30] with plastic and allows for any FDM or FFF 3D printer to be able to print with a wider range of plastics.

In 2014, Benjamin S. Cook and Manos M. Tentzeris demonstrate the first multi-material, vertically integrated printed electronics additive manufacturing platform (VIPRE) which enabled 3D printing of functional electronics operating up to 40 GHz.[31]

The term "3D printing" originally referred to a process that deposits a binder material onto a powder bed with inkjet printer heads layer by layer. More recently, the popular vernacular has started using the term to encompass a wider variety of additive-manufacturing techniques such as electron-beam additive manufacturing and selective laser melting. The United States and global technical standards use the official term additive manufacturing for this broader sense.

The most-commonly used 3D printing process (46% as of 2018) is a material extrusion technique called fused deposition modeling, or FDM.[4] While FDM technology was invented after the other two most popular technologies, stereolithography (SLA) and selective laser sintering (SLS), FDM is typically the most inexpensive of the three by a large margin, which lends to the popularity of the process.

General principles

Modeling

.jpg)

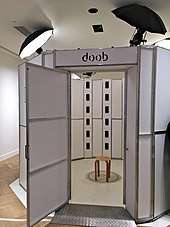

3D printable models may be created with a computer-aided design (CAD) package, via a 3D scanner, or by a plain digital camera and photogrammetry software. 3D printed models created with CAD result in relatively fewer errors than other methods. Errors in 3D printable models can be identified and corrected before printing.[32] The manual modeling process of preparing geometric data for 3D computer graphics is similar to plastic arts such as sculpting. 3D scanning is a process of collecting digital data on the shape and appearance of a real object, creating a digital model based on it.

CAD models can be saved in the stereolithography file format (STL), a de facto CAD file format for additive manufacturing that stores data based on triangulations of the surface of CAD models. STL is not tailored for additive manufacturing because it generates large file sizes of topology optimized parts and lattice structures due to the large number of surfaces involved. A newer CAD file format, the Additive Manufacturing File format (AMF) was introduced in 2011 to solve this problem. It stores information using curved triangulations.[33]

Printing

Before printing a 3D model from an STL file, it must first be examined for errors. Most CAD applications produce errors in output STL files,[34][35] of the following types:

- holes;

- faces normals;

- self-intersections;

- noise shells;

- manifold errors.[36]

A step in the STL generation known as "repair" fixes such problems in the original model.[37][38] Generally STLs that have been produced from a model obtained through 3D scanning often have more of these errors [39] as 3D scanning is often achieved by point to point acquisition/mapping. 3D reconstruction often includes errors.[40]

Once completed, the STL file needs to be processed by a piece of software called a "slicer," which converts the model into a series of thin layers and produces a G-code file containing instructions tailored to a specific type of 3D printer (FDM printers).[41] This G-code file can then be printed with 3D printing client software (which loads the G-code, and uses it to instruct the 3D printer during the 3D printing process).

Printer resolution describes layer thickness and X–Y resolution in dots per inch (dpi) or micrometers (µm). Typical layer thickness is around 100 μm (250 DPI), although some machines can print layers as thin as 16 μm (1,600 DPI).[42] X–Y resolution is comparable to that of laser printers. The particles (3D dots) are around 50 to 100 μm (510 to 250 DPI) in diameter. For that printer resolution, specifying a mesh resolution of 0.01–0.03 mm and a chord length ≤ 0.016 mm generate an optimal STL output file for a given model input file.[43] Specifying higher resolution results in larger files without increase in print quality.

Construction of a model with contemporary methods can take anywhere from several hours to several days, depending on the method used and the size and complexity of the model. Additive systems can typically reduce this time to a few hours, although it varies widely depending on the type of machine used and the size and number of models being produced simultaneously.

Finishing

Though the printer-produced resolution is sufficient for many applications, greater accuracy can be achieved by printing a slightly oversized version of the desired object in standard resolution and then removing material using a higher-resolution subtractive process.[44]

The layered structure of all Additive Manufacturing processes leads inevitably to a stair-stepping effect on part surfaces which are curved or tilted in respect to the building platform. The effects strongly depend on the orientation of a part surface inside the building process.[45]

Some printable polymers such as ABS, allow the surface finish to be smoothed and improved using chemical vapor processes[46] based on acetone or similar solvents.

Some additive manufacturing techniques are capable of using multiple materials in the course of constructing parts. These techniques are able to print in multiple colors and color combinations simultaneously, and would not necessarily require painting.

Some printing techniques require internal supports to be built for overhanging features during construction. These supports must be mechanically removed or dissolved upon completion of the print.

All of the commercialized metal 3D printers involve cutting the metal component off the metal substrate after deposition. A new process for the GMAW 3D printing allows for substrate surface modifications to remove aluminum[47] or steel.[48]

Materials

Traditionally, 3D printing focused on polymers for printing, due to the ease of manufacturing and handling polymeric materials. However, the method has rapidly evolved to not only print various polymers[49] but also metals[50][51] and ceramics,[52] making 3D printing a versatile option for manufacturing.

Multi-material 3D printing

A drawback of many existing 3D printing technologies is that they only allow one material to be printed at a time, limiting many potential applications which require the integration of different materials in the same object. Multi-material 3D printing solves this problem by allowing objects of complex and heterogeneous arrangements of materials to be manufactured using a single printer. Here, a material must be specified for each voxel (or 3D printing pixel element) inside the final object volume.

The process can be fraught with complications, however, due to the isolated and monolithic algorithms. Some commercial devices have sought to solve these issues, such as building a Spec2Fab translator, but the progress is still very limited.[53] Nonetheless, in the medical industry, a concept of 3D printed pills and vaccines has been presented.[54] With this new concept, multiple medications can be combined, which will decrease many risks. With more and more applications of multi-material 3D printing, the costs of daily life and high technology development will become inevitably lower.

Metallographic materials of 3D printing is also being researched.[55] By classifying each material, CIMP-3D can systematically perform 3D printing with multiple materials.[56]

Processes and printers

There are many different branded 3D printing processes, that can be grouped into seven categories:[57]

- Vat photopolymerization

- Material jetting

- Binder jetting

- Powder bed fusion

- Material extrusion

- Directed energy deposition

- Sheet lamination

The main differences between processes are in the way layers are deposited to create parts and in the materials that are used. Each method has its own advantages and drawbacks, which is why some companies offer a choice of powder and polymer for the material used to build the object.[58] Others sometimes use standard, off-the-shelf business paper as the build material to produce a durable prototype. The main considerations in choosing a machine are generally speed, costs of the 3D printer, of the printed prototype, choice and cost of the materials, and color capabilities.[59] Printers that work directly with metals are generally expensive. However less expensive printers can be used to make a mold, which is then used to make metal parts.[60]

ISO/ASTM52900-15 defines seven categories of Additive Manufacturing (AM) processes within its meaning: binder jetting, directed energy deposition, material extrusion, material jetting, powder bed fusion, sheet lamination, and vat photopolymerization.[61]

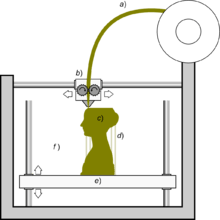

Some methods melt or soften the material to produce the layers. In Fused filament fabrication, also known as Fused deposition modeling (FDM), the model or part is produced by extruding small beads or streams of material which harden immediately to form layers. A filament of thermoplastic, metal wire, or other material is fed into an extrusion nozzle head (3D printer extruder), which heats the material and turns the flow on and off. FDM is somewhat restricted in the variation of shapes that may be fabricated. Another technique fuses parts of the layer and then moves upward in the working area, adding another layer of granules and repeating the process until the piece has built up. This process uses the unfused media to support overhangs and thin walls in the part being produced, which reduces the need for temporary auxiliary supports for the piece.[62] Recently, FFF/FDM has expanded to 3-D print directly from pellets to avoid the conversion to filament. This process is called fused particle fabrication (FPF) (or fused granular fabrication (FGF) and has the potential to use more recycled materials.[63]

Powder Bed Fusion techniques, or PBF, include several processes such as DMLS, SLS, SLM, MJF and EBM. Powder Bed Fusion processes can be used with an array of materials and their flexibility allows for geometrically complex structures,[64] making it a go to choice for many 3D printing projects. These techniques include selective laser sintering, with both metals and polymers, and direct metal laser sintering.[65] Selective laser melting does not use sintering for the fusion of powder granules but will completely melt the powder using a high-energy laser to create fully dense materials in a layer-wise method that has mechanical properties similar to those of conventional manufactured metals. Electron beam melting is a similar type of additive manufacturing technology for metal parts (e.g. titanium alloys). EBM manufactures parts by melting metal powder layer by layer with an electron beam in a high vacuum.[66][67] Another method consists of an inkjet 3D printing system, which creates the model one layer at a time by spreading a layer of powder (plaster, or resins) and printing a binder in the cross-section of the part using an inkjet-like process. With laminated object manufacturing, thin layers are cut to shape and joined together. In addition to the previously mentioned methods, HP has developed the Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) which is a powder base technique, though no laser are involved. An inkjet array applies fusing and detailing agents which are then combined by heating to create a solid layer.[68]

Other methods cure liquid materials using different sophisticated technologies, such as stereolithography. Photopolymerization is primarily used in stereolithography to produce a solid part from a liquid. Inkjet printer systems like the Objet PolyJet system spray photopolymer materials onto a build tray in ultra-thin layers (between 16 and 30 µm) until the part is completed.[69] Each photopolymer layer is cured with UV light after it is jetted, producing fully cured models that can be handled and used immediately, without post-curing. Ultra-small features can be made with the 3D micro-fabrication technique used in multiphoton photopolymerisation. Due to the nonlinear nature of photo excitation, the gel is cured to a solid only in the places where the laser was focused while the remaining gel is then washed away. Feature sizes of under 100 nm are easily produced, as well as complex structures with moving and interlocked parts.[70] Yet another approach uses a synthetic resin that is solidified using LEDs.[71]

In Mask-image-projection-based stereolithography, a 3D digital model is sliced by a set of horizontal planes. Each slice is converted into a two-dimensional mask image. The mask image is then projected onto a photocurable liquid resin surface and light is projected onto the resin to cure it in the shape of the layer.[72] Continuous liquid interface production begins with a pool of liquid photopolymer resin. Part of the pool bottom is transparent to ultraviolet light (the "window"), which causes the resin to solidify. The object rises slowly enough to allow resin to flow under and maintain contact with the bottom of the object.[73] In powder-fed directed-energy deposition, a high-power laser is used to melt metal powder supplied to the focus of the laser beam. The powder fed directed energy process is similar to Selective Laser Sintering, but the metal powder is applied only where material is being added to the part at that moment.[74][75]

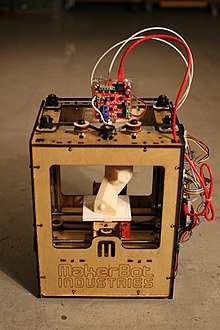

As of December 2017, additive manufacturing systems were on the market that ranged from $99 to $500,000 in price and were employed in industries including aerospace, architecture, automotive, defense, and medical replacements, among many others. For example, General Electric uses high-end 3D Printers to build parts for turbines.[76] Many of these systems are used for rapid prototyping, before mass production methods are employed. Higher education has proven to be a major buyer of desktop and professional 3D printers which industry experts generally view as a positive indicator.[77] Libraries around the world have also become locations to house smaller 3D printers for educational and community access.[78] Several projects and companies are making efforts to develop affordable 3D printers for home desktop use. Much of this work has been driven by and targeted at DIY/Maker/enthusiast/early adopter communities, with additional ties to the academic and hacker communities.[79]

Computed axial lithography is a method for 3D printing based on computerised tomography scans to create prints in photo-curable resin. It was developed by a collaboration between the University of California, Berkeley with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.[80][81][82] Unlike other methods of 3D printing it does not build models through depositing layers of material like fused deposition modelling and stereolithography, instead it creates objects using a series of 2D images projected onto a cylinder of resin.[80][82] It is notable for its ability to build an object much more quickly than other methods using resins and the ability to embed objects within the prints.[81]

Liquid additive manufacturing (LAM) is a 3D printing technique which deposits a liquid or high viscose material (e.g. Liquid Silicone Rubber) onto a build surface to create an object which then is vulcanised using heat to harden the object.[83][84][85] The process was originally created by Adrian Bowyer and was then built upon by German RepRap.[83][86][87]

Applications

.jpg)

In the current scenario, 3D printing or Additive Manufacturing has been used in manufacturing, medical, industry and sociocultural sectors which facilitate 3D printing or Additive Manufacturing to become successful commercial technology.[88] More recently, 3D printing has also been used in the humanitarian and development sector to produce a range of medical items, prosthetics, spares and repairs.[89] The earliest application of additive manufacturing was on the toolroom end of the manufacturing spectrum. For example, rapid prototyping was one of the earliest additive variants, and its mission was to reduce the lead time and cost of developing prototypes of new parts and devices, which was earlier only done with subtractive toolroom methods such as CNC milling, turning, and precision grinding.[90] In the 2010s, additive manufacturing entered production to a much greater extent.

Additive manufacturing of food is being developed by squeezing out food, layer by layer, into three-dimensional objects. A large variety of foods are appropriate candidates, such as chocolate and candy, and flat foods such as crackers, pasta,[91] and pizza.[92][93] NASA is looking into the technology in order to create 3D printed food to limit food waste and to make food that are designed to fit an astronaut's dietary needs.[94] In 2018, Italian bioengineer Giuseppe Scionti developed a technology allowing to generate fibrous plant-based meat analogues using a custom 3D bioprinter, mimicking meat texture and nutritional values.[95][96]

3D printing has entered the world of clothing, with fashion designers experimenting with 3D-printed bikinis, shoes, and dresses.[97] In commercial production Nike is using 3D printing to prototype and manufacture the 2012 Vapor Laser Talon football shoe for players of American football, and New Balance is 3D manufacturing custom-fit shoes for athletes.[97][98] 3D printing has come to the point where companies are printing consumer grade eyewear with on-demand custom fit and styling (although they cannot print the lenses). On-demand customization of glasses is possible with rapid prototyping.[99]

Vanessa Friedman, fashion director and chief fashion critic at The New York Times, says 3D printing will have a significant value for fashion companies down the road, especially if it transforms into a print-it-yourself tool for shoppers. "There's real sense that this is not going to happen anytime soon," she says, "but it will happen, and it will create dramatic change in how we think both about intellectual property and how things are in the supply chain." She adds: "Certainly some of the fabrications that brands can use will be dramatically changed by technology."[100]

In cars, trucks, and aircraft, Additive Manufacturing is beginning to transform both (1) unibody and fuselage design and production and (2) powertrain design and production. For example:

- In early 2014, Swedish supercar manufacturer Koenigsegg announced the One:1, a supercar that utilizes many components that were 3D printed.[101] Urbee is the name of the first car in the world car mounted using the technology 3D printing (its bodywork and car windows were "printed").[102][103][104]

- In 2014, Local Motors debuted Strati, a functioning vehicle that was entirely 3D Printed using ABS plastic and carbon fiber, except the powertrain.[105] In May 2015 Airbus announced that its new Airbus A350 XWB included over 1000 components manufactured by 3D printing.[106]

- In 2015, a Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon fighter jet flew with printed parts. The United States Air Force has begun to work with 3D printers, and the Israeli Air Force has also purchased a 3D printer to print spare parts.[107]

- In 2017, GE Aviation revealed that it had used design for additive manufacturing to create a helicopter engine with 16 parts instead of 900, with great potential impact on reducing the complexity of supply chains.[108]

AM's impact on firearms involves two dimensions: new manufacturing methods for established companies, and new possibilities for the making of do-it-yourself firearms. In 2012, the US-based group Defense Distributed disclosed plans to design a working plastic 3D printed firearm "that could be downloaded and reproduced by anybody with a 3D printer."[109][110] After Defense Distributed released their plans, questions were raised regarding the effects that 3D printing and widespread consumer-level CNC machining[111][112] may have on gun control effectiveness.[113][114][115][116]

Surgical uses of 3D printing-centric therapies have a history beginning in the mid-1990s with anatomical modeling for bony reconstructive surgery planning. Patient-matched implants were a natural extension of this work, leading to truly personalized implants that fit one unique individual.[117] Virtual planning of surgery and guidance using 3D printed, personalized instruments have been applied to many areas of surgery including total joint replacement and craniomaxillofacial reconstruction with great success.[118] One example of this is the bioresorbable trachial splint to treat newborns with tracheobronchomalacia[119] developed at the University of Michigan. The use of additive manufacturing for serialized production of orthopedic implants (metals) is also increasing due to the ability to efficiently create porous surface structures that facilitate osseointegration. The hearing aid and dental industries are expected to be the biggest area of future development using the custom 3D printing technology.[120]

In March 2014, surgeons in Swansea used 3D printed parts to rebuild the face of a motorcyclist who had been seriously injured in a road accident.[121] In May 2018, 3D printing has been used for the kidney transplant to save a three-year-old boy.[122] As of 2012, 3D bio-printing technology has been studied by biotechnology firms and academia for possible use in tissue engineering applications in which organs and body parts are built using inkjet printing techniques. In this process, layers of living cells are deposited onto a gel medium or sugar matrix and slowly built up to form three-dimensional structures including vascular systems.[123] Recently, a heart-on-chip has been created which matches properties of cells.[124]

In 3D printing, computer-simulated microstructures are commonly used to fabricate objects with spatially varying properties. This is achieved by dividing the volume of the desired object into smaller subcells using computer aided simulation tools and then filling these cells with appropriate microstructures during fabrication. Several different candidate structures with similar behaviours are checked against each other and the object is fabricated when an optimal set of structures are found. Advanced topology optimization methods are used to ensure the compatibility of structures in adjacent cells. This flexible approach to 3D fabrication is widely used across various disciplines from biomedical sciences where they are used to create complex bone structures[125] and human tissue[126] to robotics where they are used in the creation of soft robots with movable parts.[127][128]

3D printing has also been employed by researchers in the pharmaceutical field. During the last few years there's been a surge in academic interest regarding drug delivery with the aid of AM techniques. This technology offers a unique way for materials to be utilized in novel formulations. One of the major advantages of 3D printing, is the personalization of the dosage form that can be achieved, thus, targeting the patient's specific needs.[129] In the not-so-distant future, 3D printers are expected to reach hospitals and pharmacies in order to provide on demand production of personalized formulations according to the patients' needs.[130]

In 2018, 3D printing technology was used for the first time to create a matrix for cell immobilization in fermentation. Propionic acid production by Propionibacterium acidipropionici immobilized on 3D-printed nylon beads was chosen as a model study. It was shown that those 3D-printed beads were capable of promoting high density cell attachment and propionic acid production, which could be adapted to other fermentation bioprocesses.[131]

In 2005, academic journals had begun to report on the possible artistic applications of 3D printing technology.[132] As of 2017, domestic 3D printing was reaching a consumer audience beyond hobbyists and enthusiasts. Off the shelf machines were increasingly capable of producing practical household applications, for example, ornamental objects. Some practical examples include a working clock[133] and gears printed for home woodworking machines among other purposes.[134] Web sites associated with home 3D printing tended to include backscratchers, coat hooks, door knobs, etc.[135]

3D printing, and open source 3D printers in particular, are the latest technology making inroads into the classroom.[136][137][138] Some authors have claimed that 3D printers offer an unprecedented "revolution" in STEM education.[139][140] The evidence for such claims comes from both the low-cost ability for rapid prototyping in the classroom by students, but also the fabrication of low-cost high-quality scientific equipment from open hardware designs forming open-source labs.[141] Future applications for 3D printing might include creating open-source scientific equipment.[141][142]

In the last several years 3D printing has been intensively used by in the cultural heritage field for preservation, restoration and dissemination purposes.[143] Many Europeans and North American Museums have purchased 3D printers and actively recreate missing pieces of their relics.[144] and archaeological monuments such as Tiwanaku in Bolivia [145]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the British Museum have started using their 3D printers to create museum souvenirs that are available in the museum shops.[146] Other museums, like the National Museum of Military History and Varna Historical Museum, have gone further and sell through the online platform Threeding digital models of their artifacts, created using Artec 3D scanners, in 3D printing friendly file format, which everyone can 3D print at home.[147]

3D printed soft actuators is a growing application of 3D printing technology which has found its place in the 3D printing applications. These soft actuators are being developed to deal with soft structures and organs especially in biomedical sectors and where the interaction between human and robot is inevitable. The majority of the existing soft actuators are fabricated by conventional methods that require manual fabrication of devices, post processing/assembly, and lengthy iterations until maturity of the fabrication is achieved. Instead of the tedious and time-consuming aspects of the current fabrication processes, researchers are exploring an appropriate manufacturing approach for effective fabrication of soft actuators. Thus, 3D printed soft actuators are introduced to revolutionise the design and fabrication of soft actuators with custom geometrical, functional, and control properties in a faster and inexpensive approach. They also enable incorporation of all actuator components into a single structure eliminating the need to use external joints, adhesives, and fasteners. Circuit board manufacturing involves multiple steps which include imaging, drilling, plating, soldermask coating, nomenclature printing and surface finishes. These steps include many chemicals such as harsh solvents and acids. 3D printing circuit boards remove the need for many of these steps while still producing complex designs.[148] Polymer ink is used to create the layers of the build while silver polymer is used for creating the traces and holes used to allow electricity to flow.[149] Current circuit board manufacturing can be a tedious process depending on the design. Specified materials are gathered and sent into inner layer processing where images are printed, developed and etched. The etches cores are typically punched to add lamination tooling. The cores are then prepared for lamination. The stack-up, the buildup of a circuit board, is built and sent into lamination where the layers are bonded. The boards are then measured and drilled. Many steps may differ from this stage however for simple designs, the material goes through a plating process to plate the holes and surface. The outer image is then printed, developed and etched. After the image is defined, the material must get coated with soldermask for later soldering. Nomenclature is then added so components can be identified later. Then the surface finish is added. The boards are routed out of panel form into their singular or array form and then electrically tested. Aside from the paperwork which must be completed which proves the boards meet specifications, the boards are then packed and shipped. The benefits of 3D printing would be that the final outline is defined from the beginning, no imaging, punching or lamination is required and electrical connections are made with the silver polymer which eliminates drilling and plating. The final paperwork would also be greatly reduced due to the lack of materials required to build the circuit board. Complex designs which may takes weeks to complete through normal processing can be 3D printed, greatly reducing manufacturing time.

Legal aspects

Intellectual property

3D printing has existed for decades within certain manufacturing industries where many legal regimes, including patents, industrial design rights, copyrights, and trademarks may apply. However, there is not much jurisprudence to say how these laws will apply if 3D printers become mainstream and individuals or hobbyist communities begin manufacturing items for personal use, for non-profit distribution, or for sale.

Any of the mentioned legal regimes may prohibit the distribution of the designs used in 3D printing, or the distribution or sale of the printed item. To be allowed to do these things, where an active intellectual property was involved, a person would have to contact the owner and ask for a licence, which may come with conditions and a price. However, many patent, design and copyright laws contain a standard limitation or exception for 'private', 'non-commercial' use of inventions, designs or works of art protected under intellectual property (IP). That standard limitation or exception may leave such private, non-commercial uses outside the scope of IP rights.

Patents cover inventions including processes, machines, manufacturing, and compositions of matter and have a finite duration which varies between countries, but generally 20 years from the date of application. Therefore, if a type of wheel is patented, printing, using, or selling such a wheel could be an infringement of the patent.[150]

Copyright covers an expression[151] in a tangible, fixed medium and often lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years thereafter.[152] If someone makes a statue, they may have a copyright mark on the appearance of that statue, so if someone sees that statue, they cannot then distribute designs to print an identical or similar statue.

When a feature has both artistic (copyrightable) and functional (patentable) merits, when the question has appeared in US court, the courts have often held the feature is not copyrightable unless it can be separated from the functional aspects of the item.[152] In other countries the law and the courts may apply a different approach allowing, for example, the design of a useful device to be registered (as a whole) as an industrial design on the understanding that, in case of unauthorized copying, only the non-functional features may be claimed under design law whereas any technical features could only be claimed if covered by a valid patent.

Gun legislation and administration

The US Department of Homeland Security and the Joint Regional Intelligence Center released a memo stating that "significant advances in three-dimensional (3D) printing capabilities, availability of free digital 3D printable files for firearms components, and difficulty regulating file sharing may present public safety risks from unqualified gun seekers who obtain or manufacture 3D printed guns" and that "proposed legislation to ban 3D printing of weapons may deter, but cannot completely prevent, their production. Even if the practice is prohibited by new legislation, online distribution of these 3D printable files will be as difficult to control as any other illegally traded music, movie or software files."[153] Currently, it is not prohibited by law to manufacture firearms for personal use in the United States, as long as the firearm is not produced with the intent to be sold or transferred, and meets a few basic requirements. A license is required to manufacture firearms for sale or distribution. The law prohibits a person from assembling a non–sporting semiautomatic rifle or shotgun from 10 or more imported parts, as well as firearms that cannot be detected by metal detectors or x–ray machines. In addition, the making of an NFA firearm requires a tax payment and advance approval by ATF.[154]

Attempting to restrict the distribution of gun plans via the Internet has been likened to the futility of preventing the widespread distribution of DeCSS, which enabled DVD ripping.[155][156][157][158] After the US government had Defense Distributed take down the plans, they were still widely available via the Pirate Bay and other file sharing sites.[159] Downloads of the plans from the UK, Germany, Spain, and Brazil were heavy.[160][161] Some US legislators have proposed regulations on 3D printers to prevent them from being used for printing guns.[162][163] 3D printing advocates have suggested that such regulations would be futile, could cripple the 3D printing industry, and could infringe on free speech rights, with early pioneer of 3D printing Professor Hod Lipson suggesting that gunpowder could be controlled instead.[164][165][166][167][168][169]

Internationally, where gun controls are generally stricter than in the United States, some commentators have said the impact may be more strongly felt since alternative firearms are not as easily obtainable.[170] Officials in the United Kingdom have noted that producing a 3D printed gun would be illegal under their gun control laws.[171] Europol stated that criminals have access to other sources of weapons but noted that as technology improves, the risks of an effect would increase.[172][173]

Aerospace regulation

In the United States, the FAA has anticipated a desire to use additive manufacturing techniques and has been considering how best to regulate this process.[174] The FAA has jurisdiction over such fabrication because all aircraft parts must be made under FAA production approval or under other FAA regulatory categories.[175] In December 2016, the FAA approved the production of a 3D printed fuel nozzle for the GE LEAP engine.[176] Aviation attorney Jason Dickstein has suggested that additive manufacturing is merely a production method, and should be regulated like any other production method.[177][178] He has suggested that the FAA's focus should be on guidance to explain compliance, rather than on changing the existing rules, and that existing regulations and guidance permit a company "to develop a robust quality system that adequately reflects regulatory needs for quality assurance."[177]

Health and safety

Research on the health and safety concerns of 3D printing is new and in development due to the recent proliferation of 3D printing devices. In 2017 the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work has published a discussion paper on the processes and materials involved in 3D printing, potential implications of this technology for occupational safety and health and avenues for controlling potential hazards.[179]

Hazards

Emissions

Emissions from fused filament printers can include a large number of ultrafine particles and volatile organic compounds (VOCs).[180][181][182] The toxicity from emissions varies by source material due to differences in size, chemical properties, and quantity of emitted particles.[180] Excessive exposure to VOCs can lead to irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, headache, loss of coordination, and nausea and some of the chemical emissions of fused filament printers have also been linked to asthma.[180][183] Based on animal studies, carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers sometimes used in fused filament printing can cause pulmonary effects including inflammation, granulomas, and pulmonary fibrosis when at the nanoparticle size.[184] A National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) study noted particle emissions from a fused filament peaked a few minutes after printing started and returned to baseline levels 100 minutes after printing ended.[180] Workers may also inadvertently transport materials outside the workplace on their shoes, garments, and body, which may pose hazards for other members of the public.[185]

Carbon nanoparticle emissions and processes using powder metals are highly combustible and raise the risk of dust explosions.[186] At least one case of severe injury was noted from an explosion involved in metal powders used for fused filament printing.[187]

Other

Additional hazards include burns from hot surfaces such as lamps and print head blocks, exposure to laser or ultraviolet radiation, electrical shock, mechanical injury from being struck by moving parts, and noise and ergonomic hazards.[188][189] Other concerns involve gas and material exposures, in particular nanomaterials, material handling, static electricity, moving parts and pressures.[190]

Hazards to health and safety also exist from post-processing activities done to finish parts after they have been printed. These post-processing activities can include chemical baths, sanding, polishing, or vapor exposure to refine surface finish, as well as general subtractive manufacturing techniques such as drilling, milling, or turning to modify the printed geometry.[191] Any technique that removes material from the printed part has the potential to generate particles that can be inhaled or cause eye injury if proper personal protective equipment is not used, such as respirators or safety glasses. Caustic baths are often used to dissolve support material used by some 3D printers that allows them to print more complex shapes. These baths require personal protective equipment to prevent injury to exposed skin.[189]

Since 3-D imaging creates items by fusing materials together, there runs the risk of layer separation in some devices made using 3-D Imaging. For example, in January 2013, the US medical device company, DePuy, recalled their knee and hip replacement systems. The devices were made from layers of metal, and shavings had come loose – potentially harming the patient.[192]

Hazard controls

Hazard controls include using manufacturer-supplied covers and full enclosures, using proper ventilation, keeping workers away from the printer, using respirators, turning off the printer if it jammed, and using lower emission printers and filaments. Personal protective equipment has been found to be the least desirable control method with a recommendation that it only be used to add further protection in combination with approved emissions protection.[180]

Health regulation

Although no occupational exposure limits specific to 3D printer emissions exist, certain source materials used in 3D printing, such as carbon nanofiber and carbon nanotubes, have established occupational exposure limits at the nanoparticle size.[180][193]

As of March 2018, the US Government has set 3D printer emission standards for only a limited number of compounds. Furthermore, the few established standards address factory conditions, not home or other environments in which the printers are likely to be used.[194]

Impact

Additive manufacturing, starting with today's infancy period, requires manufacturing firms to be flexible, ever-improving users of all available technologies to remain competitive. Advocates of additive manufacturing also predict that this arc of technological development will counter globalization, as end users will do much of their own manufacturing rather than engage in trade to buy products from other people and corporations.[10] The real integration of the newer additive technologies into commercial production, however, is more a matter of complementing traditional subtractive methods rather than displacing them entirely.[195]

The futurologist Jeremy Rifkin[196] claimed that 3D printing signals the beginning of a third industrial revolution,[197] succeeding the production line assembly that dominated manufacturing starting in the late 19th century.

Social change

Since the 1950s, a number of writers and social commentators have speculated in some depth about the social and cultural changes that might result from the advent of commercially affordable additive manufacturing technology.[198] In recent years, 3D printing is creating significant impact in the humanitarian and development sector. Its potential to facilitate distributed manufacturing is resulting in supply chain and logistics benefits, by reducing the need for transportation, warehousing and wastage. Furthermore, social and economic development is being advanced through the creation of local production economies.[89]

Others have suggested that as more and more 3D printers start to enter people's homes, the conventional relationship between the home and the workplace might get further eroded.[199] Likewise, it has also been suggested that, as it becomes easier for businesses to transmit designs for new objects around the globe, so the need for high-speed freight services might also become less.[200] Finally, given the ease with which certain objects can now be replicated, it remains to be seen whether changes will be made to current copyright legislation so as to protect intellectual property rights with the new technology widely available.

As 3D printers became more accessible to consumers, online social platforms have developed to support the community.[201] This includes websites that allow users to access information such as how to build a 3D printer, as well as social forums that discuss how to improve 3D print quality and discuss 3D printing news, as well as social media websites that are dedicated to share 3D models.[202][203][204] RepRap is a wiki based website that was created to hold all information on 3d printing, and has developed into a community that aims to bring 3D printing to everyone. Furthermore, there are other sites such as Pinshape, Thingiverse and MyMiniFactory, which were created initially to allow users to post 3D files for anyone to print, allowing for decreased transaction cost of sharing 3D files. These websites have allowed greater social interaction between users, creating communities dedicated to 3D printing.

Some call attention to the conjunction of Commons-based peer production with 3D printing and other low-cost manufacturing techniques.[205][206][207] The self-reinforced fantasy of a system of eternal growth can be overcome with the development of economies of scope, and here, society can play an important role contributing to the raising of the whole productive structure to a higher plateau of more sustainable and customized productivity.[205] Further, it is true that many issues, problems, and threats arise due to the democratization of the means of production, and especially regarding the physical ones.[205] For instance, the recyclability of advanced nanomaterials is still questioned; weapons manufacturing could become easier; not to mention the implications for counterfeiting[208] and on intellectual property.[209] It might be maintained that in contrast to the industrial paradigm whose competitive dynamics were about economies of scale, Commons-based peer production 3D printing could develop economies of scope. While the advantages of scale rest on cheap global transportation, the economies of scope share infrastructure costs (intangible and tangible productive resources), taking advantage of the capabilities of the fabrication tools.[205] And following Neil Gershenfeld[210] in that "some of the least developed parts of the world need some of the most advanced technologies," Commons-based peer production and 3D printing may offer the necessary tools for thinking globally but acting locally in response to certain needs.

Larry Summers wrote about the "devastating consequences" of 3D printing and other technologies (robots, artificial intelligence, etc.) for those who perform routine tasks. In his view, "already there are more American men on disability insurance than doing production work in manufacturing. And the trends are all in the wrong direction, particularly for the less skilled, as the capacity of capital embodying artificial intelligence to replace white-collar as well as blue-collar work will increase rapidly in the years ahead." Summers recommends more vigorous cooperative efforts to address the "myriad devices" (e.g., tax havens, bank secrecy, money laundering, and regulatory arbitrage) enabling the holders of great wealth to "a paying" income and estate taxes, and to make it more difficult to accumulate great fortunes without requiring "great social contributions" in return, including: more vigorous enforcement of anti-monopoly laws, reductions in "excessive" protection for intellectual property, greater encouragement of profit-sharing schemes that may benefit workers and give them a stake in wealth accumulation, strengthening of collective bargaining arrangements, improvements in corporate governance, strengthening of financial regulation to eliminate subsidies to financial activity, easing of land-use restrictions that may cause the real estate of the rich to keep rising in value, better training for young people and retraining for displaced workers, and increased public and private investment in infrastructure development—e.g., in energy production and transportation.[211]

Michael Spence wrote that "Now comes a ... powerful, wave of digital technology that is replacing labor in increasingly complex tasks. This process of labor substitution and disintermediation has been underway for some time in service sectors—think of ATMs, online banking, enterprise resource planning, customer relationship management, mobile payment systems, and much more. This revolution is spreading to the production of goods, where robots and 3D printing are displacing labor." In his view, the vast majority of the cost of digital technologies comes at the start, in the design of hardware (e.g. 3D printers) and, more important, in creating the software that enables machines to carry out various tasks. "Once this is achieved, the marginal cost of the hardware is relatively low (and declines as scale rises), and the marginal cost of replicating the software is essentially zero. With a huge potential global market to amortize the upfront fixed costs of design and testing, the incentives to invest [in digital technologies] are compelling."[212]

Spence believes that, unlike prior digital technologies, which drove firms to deploy underutilized pools of valuable labor around the world, the motivating force in the current wave of digital technologies "is cost reduction via the replacement of labor." For example, as the cost of 3D printing technology declines, it is "easy to imagine" that production may become "extremely" local and customized. Moreover, production may occur in response to actual demand, not anticipated or forecast demand. Spence believes that labor, no matter how inexpensive, will become a less important asset for growth and employment expansion, with labor-intensive, process-oriented manufacturing becoming less effective, and that re-localization will appear in both developed and developing countries. In his view, production will not disappear, but it will be less labor-intensive, and all countries will eventually need to rebuild their growth models around digital technologies and the human capital supporting their deployment and expansion. Spence writes that "the world we are entering is one in which the most powerful global flows will be ideas and digital capital, not goods, services, and traditional capital. Adapting to this will require shifts in mindsets, policies, investments (especially in human capital), and quite possibly models of employment and distribution."[212]

Naomi Wu regards the usage of 3D printing in the Chinese classroom (where rote memorization is standard) to teach design principles and creativity as the most exciting recent development of the technology, and more generally regards 3D printing as being the next desktop publishing revolution.[213]

Environmental change

The growth of additive manufacturing could have a large impact on the environment. As opposed to traditional manufacturing, for instance, in which pieces are cut from larger blocks of material, additive manufacturing creates products layer-by-layer and prints only relevant parts, wasting much less material and thus wasting less energy in producing the raw materials needed.[214] By making only the bare structural necessities of products, additive manufacturing also could make a profound contribution to lightweighting, reducing the energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions of vehicles and other forms of transportation.[215] A case study on an airplane component made using additive manufacturing, for example, found that the component's use saves 63% of relevant energy and carbon dioxide emissions over the course of the product's lifetime.[216] In addition, previous life-cycle assessment of additive manufacturing has estimated that adopting the technology could further lower carbon dioxide emissions since 3D printing creates localized production, and products would not need to be transported long distances to reach their final destination.[217]

Continuing to adopt additive manufacturing does pose some environmental downsides, however. Despite additive manufacturing reducing waste from the subtractive manufacturing process by up to 90%, the additive manufacturing process creates other forms of waste such as non-recyclable material powders. Additive manufacturing has not yet reached its theoretical material efficiency potential of 97%, but it may get closer as the technology continues to increase productivity.[218]

See also

- 3D modeling

- 3D scanning

- 3D Printing Marketplace

- 3D bioprinting

- 3D food printing

- 3D Manufacturing Format

- 3D Printing speed

- Additive Manufacturing File Format

- Actuator

- AstroPrint

- Cloud manufacturing

- Computer numeric control

- Delta robot

- Fusion3

- Laser cutting

- Limbitless Solutions

- List of 3D printer manufacturers

- List of common 3D test models

- List of emerging technologies

- List of notable 3D printed weapons and parts

- Magnetically assisted slip casting

- MakerBot Industries

- Milling center

- Organ-on-a-chip

- Robocasting

- Self-replicating machine

- Ultimaker

- Volumetric printing

References

- "3D printing scales up". The Economist. 5 September 2013.

- Excell, Jon (23 May 2010). "The rise of additive manufacturing". The Engineer. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- "Learning Course: Additive Manufacturing – Additive Fertigung". tmg-muenchen.de.

- "Most used 3D printing technologies 2017–2018 | Statistic". Statista. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "Google Ngram Viewer". books.google.com.

- "ISO/ASTM 52900:2015 – Additive manufacturing – General principles – Terminology". iso.org. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- Zelinski, Peter (4 August 2017), "Additive manufacturing and 3D printing are two different things", Additive Manufacturing, retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Information, Reed Business (3 October 1974). "Ariadne". New Scientist. 64 (917): 80. ISSN 0262-4079.

- Ellam, Richard (26 February 2019). "3D printing: you read it here first". New Scientist. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Jane Bird (8 August 2012). "Exploring the 3D printing opportunity". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- Hideo Kodama, "A Scheme for Three-Dimensional Display by Automatic Fabrication of Three-Dimensional Model," IEICE Transactions on Electronics (Japanese Edition), vol. J64-C, No. 4, pp. 237–41, April 1981

- Hideo Kodama, "Automatic method for fabricating a three-dimensional plastic model with photo-hardening polymer," Review of Scientific Instruments, Vol. 52, No. 11, pp. 1770–73, November 1981

- 4665492, Masters, William E., "United States Patent: 4665492 - Computer automated manufacturing process and system", issued May 12, 1987

- "3-D Printing Steps into the Spotlight". Upstate Business Journal. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Wang, Ben (27 January 1999). Concurrent Design of Products, Manufacturing Processes and Systems. CRC Press. ISBN 978-90-5699-628-4.

- Jean-Claude, Andre. "Disdpositif pour realiser un modele de piece industrielle". National De La Propriete Industrielle.

- Mendoza, Hannah Rose (15 May 2015). "Alain Le Méhauté, The Man Who Submitted Patent For SLA 3D Printing Before Chuck Hull". 3dprint.com.

- Moussion, Alexandre (2014). "Interview d'Alain Le Méhauté, l'un des pères de l'impression (Interview of Alain Le Mehaute, one of the 3D printinf technologies fathers) 3D". Primante 3D.

- "3D Printing: What You Need to Know". PCMag.com. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Apparatus for Production of Three-Dimensional Objects by Stereolithography (8 August 1984)

- Freedman, David H (2012). "Layer By Layer". Technology Review. 115 (1): 50–53.

- "History of 3D Printing: When Was 3D Printing Invented?". All3DP. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Amon, C. H.; Beuth, J. L.; Weiss, L. E.; Merz, R.; Prinz, F. B. (1998). "Shape Deposition Manufacturing With Microcasting: Processing, Thermal and Mechanical Issues". Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering. 120 (3): 656–665. doi:10.1115/1.2830171. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Beck, J.E.; Fritz, B.; Siewiorek, Daniel; Weiss, Lee (1992). "Manufacturing Mechatronics Using Thermal Spray Shape Deposition" (PDF). Proceedings of the 1992 Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Prinz, F. B.; Merz, R.; Weiss, Lee (1997). Ikawa, N. (ed.). Building Parts You Could Not Build Before. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Production Engineering. London, UK: Chapman & Hall. pp. 40–44.

- "How expiring patents are ushering in the next generation of 3D printing".

- GrabCAD, GE jet engine bracket challenge

- Zelinski, Peter (2 June 2014), "How do you make a howitzer less heavy?", Modern Machine Shop

- b. Mtaho, Adam; r.Ishengoma, Fredrick (2014). "3D Printing: Developing Countries Perspectives". International Journal of Computer Applications. 104 (11): 30. arXiv:1410.5349. Bibcode:2014IJCA..104k..30R. doi:10.5120/18249-9329.

- "Filabot: Plastic Filament Maker". Kickstarter. 24 May 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "VIPRE 3D Printed Electronics". Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Jacobs, Paul Francis (1 January 1992). Rapid Prototyping & Manufacturing: Fundamentals of Stereolithography. Society of Manufacturing Engineers. ISBN 978-0-87263-425-1.

- Azman, Abdul Hadi; Vignat, Frédéric; Villeneuve, François (29 April 2018). "Cad Tools and File Format Performance Evaluation in Designing Lattice Structures for Additive Manufacturing". Jurnal Teknologi. 80 (4). doi:10.11113/jt.v80.12058. ISSN 2180-3722.

- "3D solid repair software – Fix STL polygon mesh files – LimitState:FIX". Print.limitstate.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "3D Printing Pens". yellowgurl.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- "Model Repair Service". Modelrepair.azurewebsites.net. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "Magics, the Most Powerful 3D Printing Software | Software for additive manufacturing". Software.materialise.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "netfabb Cloud Services". Netfabb.com. 15 May 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "How to repair a 3D scan for printing". Anamarva.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Fausto Bernardini, Holly E. Rushmeier (2002). "The 3D Model Acquisition Pipeline GAS" (PDF). Comput. Graph. Forum. 21 (2): 149–72. doi:10.1111/1467-8659.00574.

- Satyanarayana, B.; Prakash, Kode Jaya (2015). "Component Replication Using 3D Printing Technology". Procedia Materials Science. Elsevier BV. 10: 263–269. doi:10.1016/j.mspro.2015.06.049. ISSN 2211-8128.

- "Objet Connex 3D Printers". Objet Printer Solutions. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- "Design Guide: Preparing a File for 3D Printing" (PDF). Xometry.

- "How to Smooth 3D-Printed Parts". Machine Design. 29 April 2014.

- Delfs, P.; T̈ows, M.; Schmid, H.-J. (October 2016). "Optimized build orientation of additive manufactured parts for improved surface quality and build time". Additive Manufacturing. 12: 314–320. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2016.06.003. ISSN 2214-8604.

- Kraft, Caleb. "Smoothing Out Your 3D Prints With Acetone Vapor". Make. Make. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Haselhuhn, Amberlee S.; Gooding, Eli J.; Glover, Alexandra G.; Anzalone, Gerald C.; Wijnen, Bas; Sanders, Paul G.; Pearce, Joshua M. (2014). "Substrate Release Mechanisms for Gas Metal Arc Weld 3D Aluminum Metal Printing". 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing. 1 (4): 204. doi:10.1089/3dp.2014.0015. S2CID 135499443.

- Haselhuhn, Amberlee S.; Wijnen, Bas; Anzalone, Gerald C.; Sanders, Paul G.; Pearce, Joshua M. (2015). "In situ formation of substrate release mechanisms for gas metal arc weld metal 3-D printing". Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 226: 50. doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2015.06.038.

- Wang, Xin; Jiang, Man; Zhou, Zuowan; Gou, Jihua; Hui, David (2017). "3D printing of polymer matrix composites: A review and prospective". Composites Part B: Engineering. 110: 442–458. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.11.034.

- Rose, L. (2011). On the degradation of porous stainless steel. University of British Columbia. pp. 104–143. doi:10.14288/1.0071732.

- Zadi-Maad, Ahmad; Rohbib, Rohbib; Irawan, A (2018). "Additive manufacturing for steels: a review". IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 285 (1): 012028. Bibcode:2018MS&E..285a2028Z. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/285/1/012028.

- Galante, Raquel; G. Figueiredo-Pina, Celio; Serro, Ana Paula (2019). "Additive manufacturing of ceramics for dental applications". Dental Materials. 35 (6): 825–846. doi:10.1016/j.dental.2019.02.026. PMID 30948230.

- Spec2Fab: A reducer-tuner model for translating specifications to 3D prints. Spec2Fab. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.396.2985.

- Researchers Turn to Multi-Material 3D Printing to Develop Responsive, Versatile Smart Composites. Researchers Turn to Multi-Material 3D Printing to Develop Responsive, Versatile Smart Composites.

- CIMP-3D. CIMP-3d (in Chinese).

- CIMP-3D. CIMP-3d.

- "Additive manufacturing – General Principles – Overview of process categories and feedstock". ISO/ASTM International Standard (17296–2:2015(E)). 2015.

- Sherman, Lilli Manolis (15 November 2007). "A whole new dimension – Rich homes can afford 3D printers". The Economist.

- Wohlers, Terry. "Factors to Consider When Choosing a 3D Printer (WohlersAssociates.com, Nov/Dec 2005)".

- 3ders.org (25 September 2012). "Casting aluminum parts directly from 3D printed PLA parts". 3ders.org. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- "Standard Terminology for Additive Manufacturing – General Principles – Terminology". ASTM International – Standards Worldwide. 1 December 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "How Selective Heat Sintering Works". THRE3D.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Woern, Aubrey; Byard, Dennis; Oakley, Robert; Fiedler, Matthew; Snabes, Samantha (12 August 2018). "Fused Particle Fabrication 3-D Printing: Recycled Materials' Optimization and Mechanical Properties". Materials. 11 (8): 1413. Bibcode:2018Mate...11.1413W. doi:10.3390/ma11081413. PMC 6120030. PMID 30103532.

- "Powder Bed Fusion processes".

- "Aluminum-powder DMLS-printed part finishes race first". Machine Design. 3 March 2014.

- Hiemenz, Joe. "Rapid prototypes move to metal components (EE Times, 3/9/2007)".

- "Rapid Manufacturing by Electron Beam Melting". SMU.edu.

- "Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) by HP".

- Cameron Coward (7 April 2015). 3D Printing. DK Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-61564-745-3.

- Johnson, R. Colin. "Cheaper avenue to 65 nm? (EE Times, 3/30/2007)".

- "The World's Smallest 3D Printer". TU Wien. 12 September 2011. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "3D-printing multi-material objects in minutes instead of hours". Kurzweil Accelerating Intelligence. 22 November 2013.

- St. Fleur, Nicholas (17 March 2015). "3-D Printing Just Got 100 Times Faster". The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Beese, Allison M.; Carroll, Beth E. (2015). "Review of Mechanical Properties of Ti-6Al-4V Made by Laser-Based Additive Manufacturing Using Powder Feedstock". JOM. 68 (3): 724. Bibcode:2016JOM....68c.724B. doi:10.1007/s11837-015-1759-z.

- Gibson, Ian; Rosen, David; Stucker, Brent (2015). Additive Manufacturing Technologies. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2113-3. ISBN 978-1-4939-2112-6.

- "3D Printing: Challenges and Opportunities for International Relations". Council on Foreign Relations. 23 October 2013. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- "Despite Market Woes, 3D Printing Has a Future Thanks to Higher Education – Bold". 2 December 2015.

- "UMass Amherst Library Opens 3-D Printing Innovation Center". Library Journal. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Kalish, Jon. "A Space For DIY People To Do Their Business (NPR.org, November 28, 2010)". Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- Kelly, Brett E.; Bhattacharya, Indrasen; Heidari, Hossein; Shusteff, Maxim; Spadaccini, Christopher M.; Taylor, Hayden K. (31 January 2019). "Volumetric additive manufacturing via tomographic reconstruction". Science. 363 (6431): 1075–1079. Bibcode:2019Sci...363.1075K. doi:10.1126/science.aau7114. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 30705152.

- "Star Trek–like replicator creates entire objects in minutes". Science. 31 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Kelly, Brett; Bhattacharya, Indrasen; Shusteff, Maxim; Panas, Robert M.; Taylor, Hayden K.; Spadaccini, Christopher M. (16 May 2017). "Computed Axial Lithography (CAL): Toward Single Step 3D Printing of Arbitrary Geometries". arXiv:1705.05893 [cs.GR].

- "German RepRap introduces L280, first Liquid Additive Manufacturing (LAM) production-ready 3D printer". 3ders.org. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Davies, Sam (2 November 2018). "German RepRap to present series-ready Liquid Additive Manufacturing system at Formnext". TCT Magazine. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "German RepRap presenting Liquid Additive Manufacturing technology at RAPID+TCT". TCT Magazine. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Scott, Clare (2 November 2018). "German RepRap to Present Liquid Additive Manufacturing and L280 3D Printer at Formnext". 3DPrint.com | The Voice of 3D Printing / Additive Manufacturing. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "German RepRap develops new polyurethane material for Liquid Additive Manufacturing". TCT Magazine. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Taufik, Mohammad; Jain, Prashant K. (10 December 2016). "Additive Manufacturing: Current Scenario". Proceedings of International Conference On: Advanced Production and Industrial Engineering -ICAPIE 2016: 380–386.

- Corsini, Lucia; Aranda-Jan, Clara B.; Moultrie, James (2019). "Using digital fabrication tools to provide humanitarian and development aid in low-resource settings". Technology in Society. 58: 101117. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.02.003. ISSN 0160-791X.

- Vincent & Earls 2011

- Wong, Venessa. "A Guide to All the Food That's Fit to 3D Print (So Far)". Bloomberg.com.

- "Did BeeHex Just Hit 'Print' to Make Pizza at Home?". 27 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Foodini 3D Printer Cooks Up Meals Like the Star Trek Food Replicator". Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- "3D Printed Food System for Long Duration Space Missions". sbir.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- Bejerano, Pablo G. (28 September 2018). "Barcelona researcher develops 3D printer that makes 'steaks'". El País. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- España, Lidia Montes, Ruqayyah Moynihan, Business Insider. "A researcher has developed a plant-based meat substitute that's made with a 3D printer". Business Insider. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- "3D Printed Clothing Becoming a Reality". Resins Online. 17 June 2013. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Michael Fitzgerald (28 May 2013). "With 3-D Printing, the Shoe Really Fits". MIT Sloan Management Review. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Sharma, Rakesh (10 September 2013). "3D Custom Eyewear The Next Focal Point For 3D Printing". Forbes.com. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Alvarez, Edgar. "Fashion and technology will inevitably become one". Engagdet.

- "Koenigsegg One:1 Comes With 3D Printed Parts". Business Insider. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Conheça o Urbee, primeiro carro a ser fabricado com uma impressora 3D". tecmundo.com.br.

- Eternity, Max. "The Urbee 3D-Printed Car: Coast to Coast on 10 Gallons?".

- 3D Printed Car Creator Discusses Future of the Urbee on YouTube

- "Local Motors shows Strati, the world's first 3D-printed car". 13 January 2015.

- Simmons, Dan (6 May 2015). "Airbus had 1,000 parts 3D printed to meet deadline". BBC. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Zitun, Yoav (27 July 2015). "The 3D printer revolution comes to the IAF". Ynet News. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Zelinski, Peter (31 March 2017), "GE team secretly printed a helicopter engine, replacing 900 parts with 16", Modern Machine Shop, retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Greenberg, Andy (23 August 2012). "'Wiki Weapon Project' Aims To Create A Gun Anyone Can 3D-Print at Home". Forbes. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Poeter, Damon (24 August 2012). "Could a 'Printable Gun' Change the World?". PC Magazine. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Samsel, Aaron (23 May 2013). "3D Printers, Meet Othermill: A CNC machine for your home office (VIDEO)". Guns.com. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- "The Third Wave, CNC, Stereolithography, and the end of gun control". Popehat. 6 October 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Rosenwald, Michael S. (25 February 2013). "Weapons made with 3-D printers could test gun-control efforts". Washington Post.

- "Making guns at home: Ready, print, fire". The Economist. 16 February 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Rayner, Alex (6 May 2013). "3D-printable guns are just the start, says Cody Wilson". The Guardian. London.

- Manjoo, Farhad (8 May 2013). "3-D-printed gun: Yes, it will be possible to make weapons with 3-D printers. No, that doesn't make gun control futile". Slate.com. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Eppley, B. L.; Sadove, A. M. (1 November 1998). "Computer-generated patient models for reconstruction of cranial and facial deformities". J Craniofac Surg. 9 (6): 548–556. doi:10.1097/00001665-199811000-00011. PMID 10029769.

- Poukens, Jules (1 February 2008). "A classification of cranial implants based on the degree of difficulty in computer design and manufacture". The International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery. 4 (1): 46–50. doi:10.1002/rcs.171. PMID 18240335.

- Zopf, David A.; Hollister, Scott J.; Nelson, Marc E.; Ohye, Richard G.; Green, Glenn E. (2013). "Bioresorbable Airway Splint Created with a Three-Dimensional Printer". New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (21): 2043–5. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1206319. PMID 23697530.

- Moore, Calen (11 February 2014). "Surgeons have implanted a 3-D-printed pelvis into a U.K. cancer patient". fiercemedicaldevices.com. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- Perry, Keith (12 March 2014). "Man makes surgical history after having his shattered face rebuilt using 3D printed parts". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Boy gets kidney transplant thanks to 3D printing". Sky News. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "3D-printed sugar network to help grow artificial liver". BBC News. 2 July 2012.

- "Harvard engineers create the first fully 3D printed heart-on-a-chip". 25 October 2016.

- "TU Delft Researchers Discuss Microstructural Optimization for 3D Printing Trabecular Bone". 18 January 2019.

- "How Doctors Can Use 3D Printing to Help Their Patients Recover Faster". PharmaNext.

- Cho, Kyu-Jin; Koh, Je-Sung; Kim, Sangwoo; Chu, Won-Shik; Hong, Yongtaek; Ahn, Sung-Hoon (2009). "Review of manufacturing processes for soft biomimetic robots". International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing. 10 (3): 171–181. doi:10.1007/s12541-009-0064-6.

- Rus, Daniela; Tolley, Michael T. (2015). "Design, fabrication and control of soft robots" (PDF). Nature. 521 (7553): 467–75. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..467R. doi:10.1038/nature14543. hdl:1721.1/100772. PMID 26017446.

- Afsana; Jain, Vineet; Haider, Nafis; Jain, Keerti (20 March 2019). "3D Printing in Personalized Drug Delivery". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 24 (42): 5062–5071. doi:10.2174/1381612825666190215122208. PMID 30767736.