Planet symbols

A planet symbol (or planetary symbol) is a graphical symbol used in astrology and astronomy to represent a classical planet (including the Sun and the Moon) or one of the eight modern planets. The symbols are also used in alchemy to represent the metals that are associated with the planets. The use of these symbols is based in ancient Greco-Roman astronomy, although their current shapes are a development of the 16th century.

The classical planets with their symbols and associated metals are:

| planet | Moon | Mercury | Venus | Sun | Mars | Jupiter | Saturn |

| symbol | ☾ | ☿ | ♀ | ☉ | ♂ | ♃ | ♄ |

| metal | silver | mercury | copper | gold | iron | tin | lead |

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) discourages the use of these symbols in modern journal articles, and their style manual proposes one- and two-letter abbreviations for the names of the planets for cases where planetary symbols might be used, such as in the headings of tables.[1] The modern planets with their traditional symbols and IAU abbreviations are:

| planet | Mercury | Venus | Earth | Mars | Jupiter | Saturn | Uranus | Neptune |

| symbol | ☿ | ♀ | ♁ | ♂ | ♃ | ♄ | ⛢ | ♆ |

| IAU | Me | V | E | Ma | J | S | U | N |

The symbols of Venus and Mars are also used to represent female and male in biology and botany, following a convention introduced by Linnaeus in the 1750s.

History

Classical planets

The written symbols for Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn have been traced to forms found in late Greek papyri.[2] Early forms are also found in medieval Byzantine codices which preserve ancient horoscopes.[3] Antecedents of the planetary symbols are attested in the attributes given to classical deities, represented in simplified pictographic form in the Roman era. Bianchini's planisphere (2nd century, Louvre inv. Ma 540)[4] shows the seven planets represented by portraits of the seven corresponding gods, each with a simple representation of an attribute, as follows: Mercury has a caduceus; Venus has a cord attached to her necklace which is connected to another necklace; Mars has a spear; Jupiter has a staff; Saturn has a scythe; the Sun has a circlet with rays emanating from it; and the Moon has a headdress with a crescent attached to it.[5]

A diagram in the astronomical compendium by Johannes Kamateros (12th century) shows the Sun represented by the circle with a ray, Jupiter by the letter zeta (the initial of Zeus, Jupiter's counterpart in Greek mythology), Mars by a shield crossed by a spear, and the remaining classical planets by symbols resembling the modern ones, without the cross-mark seen in modern versions of the symbols. These cross-marks first appear in the late 15th or early 16th century. According to Maunder, the addition of crosses appears to be "an attempt to give a savour of Christianity to the symbols of the old pagan gods."[5]

The modern symbols for the seven classical planets are found in a woodcut of the seven planets in a Latin translation of Abu Ma'shar's De Magnis Coniunctionibus printed at Venice in 1506, represented as the corresponding gods riding chariots.[6]

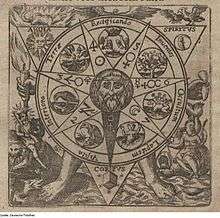

Early modern depiction of the planet symbols in an alchemical context (Musaeum Hermeticum, 1678)

Early modern depiction of the planet symbols in an alchemical context (Musaeum Hermeticum, 1678) Page spread (with the signs for Mars and Venus) from a 1515 illustrated edition of Abu Ma'shar's De Magnis Coniunctionibus (in the by translation by Herman of Carinthia, c. 1140, editio princeps by Erhard Ratdolt of Augsburg, 1489).

Page spread (with the signs for Mars and Venus) from a 1515 illustrated edition of Abu Ma'shar's De Magnis Coniunctionibus (in the by translation by Herman of Carinthia, c. 1140, editio princeps by Erhard Ratdolt of Augsburg, 1489).-850AD.png) Depiction of the planets in a 15th-century Arabic manuscript of Abu Ma'shar's "Book of nativities"[7]

Depiction of the planets in a 15th-century Arabic manuscript of Abu Ma'shar's "Book of nativities"[7] Medieval planisphere showing the zodiac and the classical planets. The planets are represented by seven faces.

Medieval planisphere showing the zodiac and the classical planets. The planets are represented by seven faces.

Earth symbol

| ⨁ ♁ | |

|---|---|

Earth symbol | |

| In Unicode | U+1F728 🜨 ALCHEMICAL SYMBOL FOR VERDIGRIS (HTML 🜨)U+2641 ♁ EARTH (HTML ♁) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Earth symbols. |

Earth is not one of the classical planets (the word "planet" by definition describing "wandering stars" as seen from Earth's surface). Its status as planet is a consequence of the development of heliocentrism. Nevertheless, there are ancient symbols for Earth, notably a cross representing the four cardinal directions, as a cross in a circle also interpreted as a globe with equator and a meridian;[8][9] This "Earth" symbol is encoded by Unicode at U+1F728 (🜨; alternative characters with similar shape are: U+2295 ⊕ CIRCLED PLUS; U+2A01 ⨁ N-ARY CIRCLED PLUS OPERATOR). In other contexts the same symbol represents the Sun and has been given the name Sun cross in modern times.

Alternatively, the globus cruciger ♁, the globe surmounted by a Christian cross, has a long tradition in Christendom as the planetary symbol for Earth. (The "globus cruciger" symbol is also used as an alchemical symbol of antimony).

Modern discoveries

Uranus ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Neptune ![]()

![]()

![]()

Pluto was also considered a planet from its discovery in 1930 until its re-classification as a "dwarf planet" in 2006. The symbol used for Pluto was a ligature of the letters P and L (Unicode U+2647 ♇).

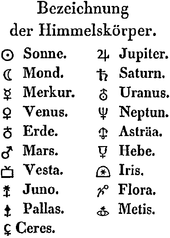

In the 19th century, symbols for the major asteroids were also in use, including Vesta (an altar with fire on it; ⚶ U+26B6), Juno (a sceptre; ⚵ U+26B5), Ceres (a reaper's scythe; ⚳ U+26B3),[8] Pallas (⚴ U+26B4); Encke (1850) has further symbols for Astraea, Hebe, Iris, Flora and Metis.[10] Unicode furthermore has a symbol (⚷ U+26B7) for 2060 Chiron (discovered 1977).

Classical planets

Moon

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Luna symbols. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crescent moon symbols. |

The crescent shape has been used to represent the Moon since earliest times. In classical anqituity, it is worn by lunar deities (Selene/Luna, Artemis/Diana, Men, etc.) either on the head or behind the shoulders, with its horns pointing upward. Its representation with the horns pointing sideways (as a heraldic crescent increscent or crescent decrescent) is early modern.

The same symbol can be used in a different context not for the Moon itself but for a lunar phase, as part of a sequence of four symbols for "new moon" (U+1F311 🌑), "waxing" (U+263D ☽), "full moon" (U+1F315 🌕) and "waning" (U+263E ☾).

Mercury

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mercury symbols. |

The symbol ![]()

Mercury symbol, representing mercury (quicksilver) mining, in the municipal coat of arms of Stahlberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mercury symbol, representing mercury (quicksilver) mining, in the municipal coat of arms of Stahlberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Venus

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Venus symbols. |

The Venus symbol (♀) consists of a circle with a small cross below it. It originates from an evolution of the initial letter of the Ancient Greek name (Phosphoros) of the planet,[25] and was dopted in Late Antiquity as an astrological symbol for the planet Venus, and hence as an old and obsolete alchemical symbol for copper. In modern times, it is still used as the astronomical symbol for Venus, although its use is discouraged by the International Astronomical Union.[1]

In botany and biology, it is used to represent the female sex (alongside the astrological symbol for Mars representing the male sex),[26] following a convention introduced by Linnaeus in the 1750s.[27] Arising from the biological convention, the symbol also came to be used in sociological contexts to represent women or femininity.

The symbol appears without the cross-mark (⚲) in Johannes Kamateros (12th century). In the Bianchini's planisphere (2nd century), Venus is represented by a necklace.[4] The (mistaken) idea that the symbol represents the goddess's hand mirror was introduced by Joseph Justus Scaliger in the late 16th century.[25] [28] Claudius Salmasius, in the early 17th century, established that it derived from the Greek abbreviation for Phosphoros, the planet's name.[25]

Unicode encodes the FEMALE SIGN at U+2640 (♀), in the Miscellaneous Symbols block.[29]

Medieval (Johannes Kamateros, 12th century) form of the Venus symbol; the horizontal stroke was added to form a Christian cross in the early modern period.[30]

Medieval (Johannes Kamateros, 12th century) form of the Venus symbol; the horizontal stroke was added to form a Christian cross in the early modern period.[30] The Venus symbol in the municipal coat of arms of Falun Municipality in Sweden (1932), here representing copper mining.[31]

The Venus symbol in the municipal coat of arms of Falun Municipality in Sweden (1932), here representing copper mining.[31]

Sun

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sun symbols. |

The modern astronomical symbol for the Sun (circled dot, Unicode U+2609 ☉) was first used in the Renaissance.

Bianchini's planisphere, produced in the 2nd century, has a circlet with rays radiating from it.[5][4] A diagram in Johannes Kamateros' 12th century Compendium of Astrology shows the Sun represented by a circle with a ray.[33] This older symbol is encoded by Unicode (version 9.0, June 2016) as "ALCHEMICAL SYMBOL FOR GOLD" (🜚 U+1F71A) in the Alchemical Symbols block.

Medieval (Johannes Kamateros, 12th century)[30] astronomical symbol for the Sun (and alchemical symbol for gold)

Medieval (Johannes Kamateros, 12th century)[30] astronomical symbol for the Sun (and alchemical symbol for gold)

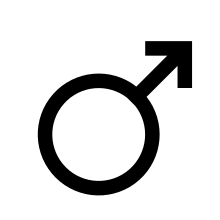

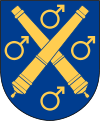

Mars

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mars symbols. |

The Mars symbol (♂) is a depiction of a circle with an arrow emerging from it, pointing at an angle to the upper right. As astrological symbol it represents the planet Mars. It is also the old and obsolete symbol for iron in alchemy. In biology and botany, it is used to represent the male sex (alongside the astrological symbol for Venus representing the female sex),[26] following a convention introduced by Linnaeus in the 1750s.[27]

The symbol in its current form represents spear and shield and dates to the early 16th century. It is derived from a medieval form where the spear was drawn across the shield, which in turn was based on a convention used in antiquity (Bianchini's planisphere) which represented Mars by a spear.[4] A diagram in the 12th-century Compendium of Astrology by Johannes Kamateros represents Mars by a shield crossed by a spear.[33]

The Mars symbol (representing iron mining) in the municipal coat of arms of Karlskoga in Sweden

The Mars symbol (representing iron mining) in the municipal coat of arms of Karlskoga in Sweden

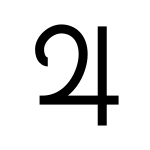

Jupiter

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jupiter symbols. |

The origin of the symbol for Jupiter ![]()

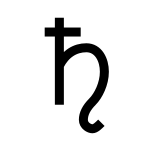

Saturn

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saturn symbols. |

Saturn is usually depicted with a scythe or sickle, and the planetary symbol has apparently evolved from a picture of this attribute, in Kamateros (12th century) shown in a shape similar to the letter eta η, with the horizontal stroke added along with the "Christianization" of the other symbols in the early 16th century, ![]()

Emblem of the Fraternitas Saturni, a German magical order founded in 1926.

Emblem of the Fraternitas Saturni, a German magical order founded in 1926. The Saturn symbol representing lead in the municipal coat of arms of Bleiwäsche, since 1975 part of Bad Wünnenberg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

The Saturn symbol representing lead in the municipal coat of arms of Bleiwäsche, since 1975 part of Bad Wünnenberg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Minor planets

| Unicode symbol | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pluto |  |

|

(♇) PLUTO at U+2647.[36] | ||

| Ceres |  |

|

(⚳) CERES at U+26B3.[36] | ||

| Pallas |  |

|

(⚴) PALLAS at U+26B4.[36] | ||

| Juno |  |

|

(⚵) JUNO at U+26B5.[36] | ||

| Vesta |  |

|

(⚶) VESTA at U+26B6.[36] | ||

| Chiron |

|

(⚷) CHIRON at U+26B7.[36] |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Planet symbols. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alchemical symbols. |

- Astrological symbol

- Astronomical symbol

- Gender symbol

- Classical planets in Western alchemy

References

- The IAU Style Manual (PDF). 1989. p. 27.

- Jones, Alexander (1999). Astronomical papyri from Oxyrhynchus. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-87169-233-3.

- Neugebauer, Otto (1975). A history of ancient mathematical astronomy. pp. 788–789. ISBN 0-387-06995-X.

- "Bianchini's planisphere". Florence, Italy: Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza (Institute and Museum of the History of Science). Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- Maunder (1934)

- Maunder (1934:239)

- BNF Arabe 2583 fol. 15v. Saturn is shown as a black bearded man, kneeling and holding a scythe or axe; Mercury is shown as a scribe holding an open codex; Jupiter as a man of the law wearing a turban; Venus as a lute-player; Mars as a helmeted warrior holding a sword and the head of an enemy.

- The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 22. C. Knight. 1842. p. 197.

- The Encyclopedia Americana: a library of universal knowledge. 26. Encyclopedia Americana Corp. 1920. pp. 162–163. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- Johann Franz Encke, Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch für 1853, Berlin 1850, p. VIII

- Bode, J. E. (1784). Von dem neu entdeckten Planeten. Beim Verfaszer. pp. 95–96.

- Gould, B. A. (1850). Report on the history of the discovery of Neptune. Smithsonian Institution. p. 5.

- Cain, Fraser. "Symbol for Uranus". Universe Today. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- Francisca Herschel (August 1917). "The meaning of the symbol H+o for the planet Uranus". The Observatory. 40: 306. Bibcode:1917Obs....40..306H.

- Schumacher, H. C. (1846). "Name des Neuen Planeten". Astronomische Nachrichten. 25: 81–82. Bibcode:1846AN.....25...81L. doi:10.1002/asna.18470250603.

- Littmann, Mark; Standish, E. M. (2004). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. Courier Dover Publications. p. 50. ISBN 0-486-43602-0.

- Pillans, James (1847). "Ueber den Namen des neuen Planeten". Astronomische Nachrichten. 25 (26): 389–392. Bibcode:1847AN.....25..389.. doi:10.1002/asna.18470252602.

- Baum, Richard; Sheehan, William (2003). In Search of Planet Vulcan: The Ghost in Newton's Clockwork Universe. Basic Books. pp. 109–110. ISBN 0-7382-0889-2.

- Gingerich, Owen (October 1958). "The Naming of Uranus and Neptune". Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. 8 (352): 9–15. Bibcode:1958ASPL....8....9G.

- Hind, J. R. (1847). "Second report of proceedings in the Cambridge Observatory relating to the new Planet (Neptune)". Astronomische Nachrichten. 25 (21): 309–314. Bibcode:1847AN.....25..309.. doi:10.1002/asna.18470252102.

- Bureau Des Longitudes, France (1847). Connaissance des temps: ou des mouvementes célestes, à l'usage des astronomes. p. unnumbered front matter.

- Cox, Arthur (2001). Allen's astrophysical quantities. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 0-387-95189-X.

- Mattison, Hiram (1872). High-School Astronomy. Sheldon & Co. pp. 32–36.

- "staff and winged helmet of Mercury" Tim Collins, Behind the Lost Symbol (2010), p. 128

- Stearn, William T. (17 August 1961). "The Male and Female Symbols of Biology". New Scientist (248): 412–413.

- Schott, GD (December 2005). "Sex symbols ancient and modern: their origins and iconography on the pedigree" (PDF). The BMJ. 331 (7531): 1509–10. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1509. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1322246. PMID 16373733. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Stearn, William T. (May 1962). "The Origin of the Male and Female Symbols of Biology" (PDF). Taxon. 11 (4): 109–113. doi:10.2307/1217734. ISSN 0040-0262. JSTOR 1217734. "In his Systema Naturae (Leyden, 1735) he Linnaeus used them with their traditional associations for metals. Their first biological use is in the Linnaean dissertation Plantae hybridae xxx sistit J. J. Haartman (1751) where in discussing hybrid plants Linnaeus denoted the supposed female parent species by the sign ♀, the male parent by the sign ♂, the hybrid by ☿ 'matrem signo ♀, patrem ♂ & plantam hybridam ☿ designavero'. In subsequent publications he retained the signs ♀ and ♂ for male and female individuals but discarded ☿ for hybrids; the last are now indicated by the multiplication sign ×. Linnaeus's first general use of the signs of ♀ and ♂ was in his Species Plantarum (1753) written between 1746 and 1752 and surveying concisely the whole plant kingdom as then known." (p. 110)

- see Hiram Mattison, A high-school astronomy (1857), p. 32.

- In the official code chart glossed " = Venus = alchemical symbol for copper → 1F469 👩 woman → 1F6BA 🚺 womens symbol".

- Maunder (1934), p. 245.

- Falun was the site of a copper mine from at least the 13th century. A coat of arms including a copper sign is recorded for 1642; the current design dates to the early 20th century, and was given official recognition in 1932. It was slightly simplified upon the formation of the modern municipality in 1971 (registered with the Swedish Patent and Registration Office. in 1988).

- Claimed to have been designed by Robin Morgan in the 1960s. "Morgan designed the universal logo of the women's movement, the woman's symbol centered with a raised fist" (robinmorgan.net)

- Neugebauer, Otto; Van Hoesen, H. B. (1987). Greek Horoscopes. pp. 1, 159, 163.

- Maunder (1934), p. 244.

- Pat Ward, Barbara Ward, Space Frontiers, Grades 4 - 8: EXPLORING Astronomy, Carson-Dellosa Publishing, 22 Oct 2012 p. 42 (without further reference).

- In the official code chart.

- Maunder, A. S. D. (1934). "The origin of the symbols of the planets". The Observatory. 57: 238–247. Bibcode:1934Obs....57..238M.