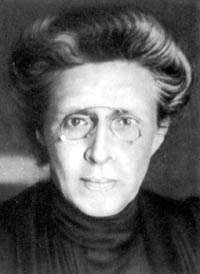

Elena Stasova

| Elena Stasova | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chairman of the Secretariat of the Russian Communist Party | |

|

In office March 1919 – December 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Yakov Sverdlov |

| Succeeded by |

Nikolay Krestinsky (as Responsible Secretary) |

| Technical Secretary of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party | |

|

In office April 1917 – 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by |

Yakov Sverdlov (as Chairman of the Secretariat) |

| Candidate member of the 7th, 8th Politburo | |

|

In office 13 April – 26 September 1919 | |

|

In office 11 March – 25 March 1919 | |

| Member of the 6th, 7th, 8th Secretariat | |

|

In office 6 August 1917 – 5 April 1920 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

3 October 1873 St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died |

31 December 1966 (aged 93) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Citizenship | Soviet |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political party | Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) |

Elena Dmitrievna Stasova (Russian: Еле́на Дми́триевна Ста́сова, IPA: [jɪˈlʲɛnə ˈdmʲitrʲɪɪvnə ˈstasəvə]; 3 October 1873 – 31 December 1966) was a Russian communist revolutionary who became a political functionary working for the Communist International (Comintern). She was a Comintern representative to Germany in 1921. From 1927 to 1937 she was the president of International Red Aid (MOPR). From 1938 to 1946 she worked on the editorial staff of the magazine International Literature.

Biography

Early years

Elena Stasova was born in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1873 to an ethnic Russian family. She was the daughter of a liberal jurist, Dmitry Stasov (1828–1918) who worked in the Senate, was a Herald at the coronation of Alexander II, and was the defence counsel at the trial of Dmitry Karakozov, the first of the revolutionaries to attempt to assassinate Alexander II, and at the largest of the Tsarist political trials, the Trial of the 193. Her grandfather had been architect to Tsars Alexander I and Nicholas I.[1] Her uncle was art critic Vladimir Stasov.

After finishing secondary school, Elena became a committed socialist and joined the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party (RSDRP) at the time of its establishment in 1898.[2]

When the RSDRP split into Bolshevik and Menshevik factions in 1903, Stasova cast her lot with Lenin and the Bolsheviks as a professional revolutionary. Over the next two years Stasova adopted the pseudonyms "Absolute" and "Thick" and served as the conduit for Lenin's newspaper, Iskra, in St. Petersburg,[3] where she worked as party secretary of that city. She taught new members how to encode and decode. Stasova also served as secretary of the Northern Bureau of the Bolshevik Central Committee, and in other leading party positions.[4] Other pseudonyms which Stasova used during the underground period included "Delta," "Heron," "Knol," and "Varvara Ivanovna."[5]

Stasova emigrated to Geneva, Switzerland in 1905, where she was at the time of the Russian Revolution of 1905. She returned home in January 1906 to direct Bolshevik work in Tiflis (now Tbilisi), the capital of Georgia.[6]

In January 1912, Stasova was elected as an alternate member of the Bolshevik party's Central Committee. She was then secretary to the party's Russian bureau.[7] This was followed in 1913 by arrest and exile to Siberia, where she remained until 1916.[8] She had left the party treasury with her brother.

Political career

After the February Revolution of 1917, Stasova was named a secretary of the Central Committee — a position which she retained through the October Revolution, finally standing down in March 1920.[9] She was also returned as an alternate member of the Bolshevik Central Committee by the 6th Congress of the Russian Communist Party in 1917. She was the only woman elected to full membership on the CC by the 7th Congress of 1918 and the 8th Congress of 1919. However, the 9th Congress of 1920 dropped her both from the Central Committee and from the party secretariat.[10]

After being removed from the Central Committee, Stasova worked for the Petrograd party organization, from where she was brought into the Comintern's apparatus. She was appointed Comintern representative to the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in May 1921, where she used the pseudonym "Hertha."[11] Stasova remained in Germany through 1926, where she played a leading role in the German affiliate of the International Red Aid (MOPR) organization, Die Rote Hilfe.[12]

Stasova returned to the USSR in February 1926.[13] The next year she was named deputy director head of the international MOPR as well as head of the Central Committee of the MOPR organization in the USSR, positions which she retained through 1937.[14]

Stasova served as a member of the Central Control Commission of the Russian Communist Party from 1930 to 1934 and in 1935 the 7th World Congress of the Comintern named her a member of the International Control Commission.[15]

Unlike so many other "Old Bolsheviks," Stasova was not arrested during the spy mania and secret police terror which swept the Soviet Union in the late 1930s, although in November 1937, Josif Stalin told the head of Comintern, Georgi Dimitrov that Stasova was "scum" and "probably" would be arrested. She was dismissed from her post on MOPR five days later, on 16 November 1937.[16] Unusually, she retained her place on the International Control Commission until Comintern was abolished in 1943[17], and in 1938 was re-employed as an editor of the magazine International Literature. Stasova continued in this role until 1946, when she retired.[18]

Death and legacy

After Stalin's death, Elena Stasova was the last surviving Old Bolshevik who had served on the Central Committee during the 1917 revolution. She made very few public appearances after retiring, but in 1961, she was one of four Old Bolsheviks who signed an appeal to the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union for the posthumous rehabilitation of Nikolai Bukharin.[19] She died on 31 December 1966.

A boarding school for foreigners in Ivanovo, Russia called the Ivanovo International Boarding School ("Interdom"), established by MOPR in 1933, was named after Elena Stasova.

Writings

- MOPR's Banners Abroad: Report to the Third MOPR Congress of the Soviet Union. Moscow: Executive Committee of International Red Aid, 1931. (By-line given as "H. Stassova" on cover.)

Honours and awards

Footnotes

- ↑ Simon Sebag Montefiore, Young Stalin, page 209

- ↑ Branko Lazitch and Milorad M. Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern: New, Revised, and Expanded Edition. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1986; pg. 444.

- ↑ N.K. Krupskaya, Reminiscences of Lenin. Bernard Isaacs, trans. New York: International Publishers, 1970; pg. 77.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ Reference Index to V.I. Lenin Collected Works: Part One: Index of Works, Name Index. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1978; pg. 312.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ Simon Sebag Montefiore, Young Stalin, page 205

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ G.M. Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) - VKP(b) i Komintern: 1919-1943 Dokumenty ("Politburo CC RKP(b)-VKP(b) and the Comintern: 1919-1943 Documents"). Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2004; pg. 885.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 445.

- ↑ Dimitrov, Georgi (2003). The Diary of Georgi Dimitrov 1933-1949. New Haven: Yale U.P. pp. 69, 72. ISBN 0-300-09794-8.

- ↑ Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) - VKP(b) i Komintern, pg. 885.

- ↑ Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 444.

- ↑ Medvedev, Roy (1971). Let History Judge, The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 184.

Further reading

- Barbara Evan Clements, Bolshevik Women, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997