Niijima Yae

| Niijima Yae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | 新島 八重 |

| Born |

Yamamoto Yae (山本 八重) 1 December 1845 Aizu, Mutsu Province, Japan |

| Died |

14 June 1932 (aged 86) Kyoto, Kyoto Prefecture, Japan |

| Resting place | Doshisha Cemetery, Kyoto, Japan |

| Residence | Teramachi Street, Kyoto, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Other names | Yamamoto Yaeko (山本 八重子) |

| Occupation | Nurse, former soldier |

| Home town | Kyoto, Kyoto Prefecture, Japan |

| Spouse(s) |

Shonosuke Kawasaki (m. 1865; div. 1871) |

| Children | none |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Yamamoto Kakuma (brother) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Aizu Domain |

| Years of service | 1868 |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Aizu |

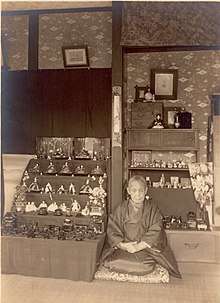

Niijima Yae (新島 八重, born Yamamoto Yae (山本 八重); 1 December 1845 – 14 June 1932), also known as Yamamoto Yaeko (山本 八重子), was a Japanese woman of the late Edo period who lived into the early Shōwa period. She was famously known as the wife of Joseph Hardy Neesima, the founder of Doshisha University and Doshisha Women's College of Liberal Arts.

Yaeko served as a nurse during the Russo-Japanese War and Sino-Japanese War, and became the first woman outside of Imperial House of Japan to be decorated for her service to the country.[1]

Early life

Yamamoto Yae was born the daughter of Yamamoto Gonpachi, a samurai and one of the official gunnery instructors in Aizu Domain and his wife Saku. Her family claimed descent from the Takeda clan's retainer Yamamoto Kansuke.[2] In 1865, she was married to Shonosuke Kawasaki, a Rangaku scholar from Izushi Domain.

Boshin War

Yae was skilled in gunnery, which was highly unusual for a woman of Bakumatsu period. She took part in the defense of Aizu when the Boshin War broke out in 1868. During the Battle of Aizu, she fought against the Meiji government and the coalition forces, defending the Aizuwakamatsu Castle with her Spencer repeating rifle along with Aizu warriors.[3]

After the surrender of Aizu Domain, Yaeko took shelter in nearby Yonezawa Domain in Yonezawa, Yamagata and stayed there for one year.[4] Yae and her husband had since separated after the defeat of Aizu as Shonosuke became a prisoner of war. Their divorce was finalised in 1871.[5]

In Kyoto

In 1871, she traveled to Kyoto to look for her brother Yamamoto Kakuma, who spent years as a prisoner of war in Satsuma custody. Upon her arrival to Kyoto, Yaeko was hired as a substitute instructor in Kyoto Women's School (ja) through the recommendation from her brother Kakuma, now working as an advisor for Kyoto prefectural government.

While Yaeko was working at the women's school, she was acquainted with sadō instructor from the house of Urasenke. Through their interaction, Yaeko was able to familiarise herself with the art of Japanese tea ceremony. She obtained the qualification later in 1894 and became a tea master of the Urasenke tradition, with the art-name of Niijima Sōchiku (新島宗竹). During her tenure at the school, she was also acquainted with kadō instructor from the house of Ikenobō. She was later granted the certificate to practice flower arrangement from Ikenobō in 1896.[6]

Throughout the early 1870s, Yaeko remained in Kyoto and became a Christian after she met Rev. Joseph Hardy Neesima, who used to visit her brother Kakuma back when they were in Aizu. The two of them were engaged soon after in October 1875. Neesima was a former samurai who spent 10 years in the United States from 1864–74 to pursue higher education. He returned to Japan in 1874, and was in the process of building a Western school that promoted Christianity. However, the concept was vehemently opposed by Buddhists and Shintoists in Kyoto, and they submitted several complaints to the prefectural government. Soon after they were engaged, Yaeko was dismissed from her position in the women's school following pressure from the government.[7]

Yaeko and Neesima were married on 3 January 1876. Together with Neesima and Kakuma, Yaeko volunteered to assist in running the new school. She played an integral role in the founding of Doshisha University and its subsequent development. Neesima was educated in the United States, and he was a believer in women's rights. While it contradicted social norms of Edo period Japan, it happened to be balancing for a spirited woman like Yaeko. The courtesy given by Neesima toward Yaeko was viewed as a sign of shrewishness on the part of Yaeko, and she was consequently criticised as a "bad wife" by Japanese society throughout their marriage.[8] Contrary to traditional Japanese couples, Neesima and Yaeko were friendly to each other. He praised her lifestyle as "handsome" in his letter to friends in United States.[1]

Later career

Following the sudden death of Neesima on 23 January 1890, Yaeko and her colleagues in Doshisha University began to drift apart gradually. Doshisha students from Satsuma and Chōshū Domain were not warmly received by her, since they attacked Aizu during the Boshin War.[1] In her later career, Yaeko turned her focus to nursing and became a member of Japanese Red Cross on 26 April 1890. During the First Sino-Japanese War, she joined the army and spent four months as a nurse stationed in Hiroshima.[9] Yaeko led a team of 40 nurses to care for the wounded soldiers while working to improve the social status of trained nurses. Her efforts were recognised by the Japanese government, and she was awarded her first Order of the Precious Crown in 1896.[9][10]

In between the wars, she worked as an instructor in nursing schools. When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, she joined the army again and served as a volunteer nurse at Imperial Japanese Army hospital in Osaka for two months. For this service she received her second Order of the Precious Crown.[9] She was further awarded a silver cup at the inauguration of Shōwa Emperor in 1928 for her overall commitment to the country.

Death

While Yaeko did not bear any children from her two marriages, she did adopt three children from Yonezawa Domain throughout her life. However, they were not closely connected. In her final years, she maintained her residence on Teramachi Street in Kyoto until she died on 14 June 1932 at the age of 86. She was given a funeral sponsored by Doshisha University. Her burial site is located at Doshisha Cemetery in Sakyō-ku, Kyoto.[11]

Honours

In popular culture

Niijima Yae is a popular historical figure in Japan, and has appeared in various stories, comics (manga), and TV shows.

- Stories

- Fukumoto Takehisa (ja), Niijima Yae series

- Mitsugu Saotome, Meiji no Keimai (1990) ISBN 978-4404017932

- Manga

- Yae no Sakura, (2013) ISBN 978-4-08-870674-0, published by Shueisha. The story was written by Yamamoto Mutsumi, and it was drawn into comic by Takemura Youhei.

- TV

- The 2007 drama Byakkotai (ja) by TV Asahi, where she was portrayed by Nakagoshi Noriko.

- Yae no Sakura, the 2013 NHK taiga drama, where she is the main protagonist and portrayed by Haruka Ayase.[12]

- Games

- Tecmo Koei, Toukiden (2013)

Notes

- 1 2 3 "歴史秘話ヒストリア「明治悪妻伝説 初代"ハンサムウーマン"新島八重の生涯". NHK. April 22, 2009.

- ↑ Suzuki 1998

- 1 2 3 "新島八重×同志社女子大学". Doshisha Women's College of Liberal Arts. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ↑ "新島八重の米沢居住に裏付け 市立図書館で新史料見つかる』山形新聞". Yamagata News Online. August 28, 2012.

- ↑ Asakura 2012

- ↑ "The Archives in the Repository of Neesima memorabilia: 門弟許可状". Doshisha University. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ↑ Boller 1947, p. 41

- ↑ "歴史秘話ヒストリア「"ハンサムウーマン"がゆく 新島八重 不屈の会津魂". NHK. January 9, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "第III期 日本のナイチンゲール―会津魂再び". Doshisha Women's College of Liberal Arts. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ↑ "叙任及辞令・明治29年12月25日". 官報. 内閣官報局. 1897-01-04. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ "同志社墓地の案内". Doshisha University. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ↑ Corkill, Edan (January 4, 2013). "NHK spotlights gunslinging daughter of the north in yearlong Sunday drama". The Japan Times.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Niijima Yae. |

- Boller, Paul F. (1947), The American Board and the Doshisha, 1875–1900, New Haven: Yale University Press

- Suzuki, Yukiko (1998), 闇はわれを阻まず-山本覚馬伝, Tokyo: Shogakukan, ISBN 978-4093792158

- Shiba, Gorō (1999), Remembering Aizu: The Testament of Shiba Gorō, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press

- Asakura, Yuu (2012), 川崎尚之助と八重―一途に生きた男の生涯, Tokyo: Chido Publishing, ISBN 978-4886642455