Workmen's Village, Amarna

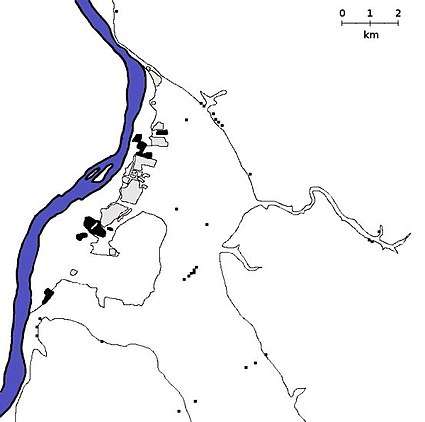

Located in the desert east of the ancient city of Akhetaten, the Workmen's village at Amarna was built during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten (c. 1349-1332 BCE) and the concurrent growth of Akhetaten. While today a mostly isolation part of the Akhetaten site in comparison towards other parts including the main city, The Workmen's Village helps provide many well preserved artifacts and buildings therefore allowing archaeologists who visit to gather much information of how the society here worked before the abandonment of Akhetaten after Akhenaten's death.

Archaeological history

The Workingmen’s Village at Tell el-Amarna was first excavated around 1921 during the height of Egyptian research by Western archaeologists. Though no confirmation of which archaeologist led this particular excavation has ever appeared, one account by archaeologists T. Eric Peet and Leonard Woolley found publication around 1923 within their book The City of Akhenaten. While the site was first excavated partially between 1921 and 1922, a revival of excavating the village uncovered far more archaeological finds between the years of 1979-1986. Among those present during the secondary excavation period was American archaeologist Barry J. Kemp who published numerous books and articles pertaining to Amarna between the years of 1984-1987 with much detail given to the Workingmen’s Village.

Walled village

The majority of living quarters for the residents of this village are within a 69 square mile wide area surrounded by a wall to the west of the main chapels. A total of 72 houses are found inside this area, each showing parallel order and separated by roads thereby allowing villagers living inside this area to walk alongside said roads to their own homes. The entrance into this village uses a narrow passage in which the villagers who reside in this area use for both entering and exiting on a daily basis. Throughout both periods of excavations, numerous items which normally found use in the daily lives of the village’s residents are found within these homes, one of the most common being tiny crafted scarabs meant for receiving a blessing from the god named Aten, based from then-Pharaoh Akhenaten’s religious viewpoints.

Chapels and their wall paintings

Outside of the walled portion of the village, apparently 23 chapels were built by the villagers throughout its history. These chapels generally compose of mud brick and stone for their construction and often include brick benches so their internal decorations and elaborate wall paintings. The main chapel in particular, located in the center of the village and to the southeast of the walled village, houses depictions of vultures, winged sun discs, lotus flowers piling into an almost bouquet pattern, painted on the eastern wall of its main sanctuary. During the days of Pharaoh Akhenaten’s reign, the main chapel’s primary color for the main structure’s walls came in white plaster via the coating process of applying marl plaster. From this point, the chapels in this village now find elegant designs of various animals and other traditional Egyptian symbols meant for various deities painted on the walls, courtesy of the builders using gypsum pigments of colors instead of the whitewash coloring used for the rest of the chapel’s structure.

Unfortunately, many of these wall paintings are left into fragments spread across the chapel and some plaster to the walls incomplete since the paintings, in the aforementioned context, consist of gypsum plaster in which generally breaks into pieces in the midst of the site decay after centuries of abandonment. While this case of wall painting decay proves being true for the main chapel and approximately five others, the fact much of the wall painting plaster fragments are uncovered throughout the excavations helps modern archaeologists interpret and even reassemble the paintings from which these pigmented fragments came from.

The purpose for the chapels was to, according to British archaeologist and researcher Fran Weatherhead, “experience a sense of communion with spirits”.[1] In context, the presence of the chapels across the village helps bring its people opportunities of making offerings for both their deities and also recently deceased loved ones as evidenced by the fact the majority of the chapels are built merely close to a rather large area of tombs north of said chapels. Therefore, the notion of recently deceased loved ones entering the afterlife justifies the presence of an offering altar within the main chapel in which implies the others housing similar looking altars for a very similar purpose. Ultimately, a distinction between every one of these chapels comes in both the deities worshiped and their respected symbols painted on the walls.

Significance of this village

In general, the site of Akhetaten dedicates the vast majority of wall painting into not only displaying the god Aten alongside the royal family yet rather the walls paintings showcase the daily lives of the citizens of Akhetaten being prosperous, joyful and above all lively. Since a majority of these wall paintings in the main city are destroyed with very little fragments left behind, the Workmen’s village’s greater number of fragments can provide a better chance of archaeologists understanding of this site’s societal norms during the Akhetaten period. The purpose for the village itself provides workers for constructing various tombs, temples, and other royally commissioned projects across the Amarna site, all in which contribute into the religious reforms of worshiping the god Aten Pharaoh Akhenaten establishes during his reign.

Religious significance

During Pharaoh Akhenaten’s reign, the god Aten receives a significant amount of importance into his religious views. According to Akhenaten, Aten guides him towards a natural sunset horizon set between Memphis and Thebes in which the Pharaoh convinces himself of being Aten’s birthplace. From here, the Pharaoh commissions the construction of a new capital built on the grounds where this sunset horizon occurs in which becomes complete during his sixth year in power. Akhenaten’s devotion for Aten eventually culminates with his reforms in the religious part of Egyptian society in which turn all worshiping into the royal family who in turn worship Aten. The construction of various temples, tombs, elite housing and other royally commissioned projects each house a certain painting or hieroglyph passage meant for the certain religious viewpoint Akhenaten imposes via his reforms. So the very presence of chapels in the Workmen’s village dedicated for deceased loved ones and other deities helps prove the existence of religious buildings outside of Akhenaten’s Aten-centric religious reformation and provide the villagers a chance of worshiping the deities worshiped prior to this period.

Major scholars related to this site's analysis

During the excavations of 1921-1922, archaeologist T.E. Peet infers the recent uncovered village being “the home of tomb diggers and grave tenders of the city (City of Akhenaten Vol. I pg.52)"[2] Of course, Mr. Peet’s hypothesis proves not entirely correct given the amount of content not yet uncovered during that point.

Professor Barry Kemp from the University of Cambridge studied the site of Tell el-Amarna since the excavations led by Egypt Exploration Society began in the year of 1979 and since then writes a very wide range of books and articles all relating to the site. In his viewpoints, Kemp takes a great interest of the lifestyle for the inhabitants of ancient Egypt’s cities and villages. He directly refers to Peet’s hypothesis in his 1986 retrospect of the village’s excavation for hoe Peet came into his conclusion given what sites, in particular Dier el-Medina, were excavated and the fact the share a great amount of similarities.

Over time, many more important scholars take into consideration of the Workmen’s village and its contribution into the overall picture of Amarna including Cambridge University’s Fran Weatherhead who goes on publishing The Main Chapel at the Amarna Workmen’s Village and its Wall Paintings alongside Kemp in 2007. In recent times, a website funded by the Colorado-based Amarna Research Foundation and United Kingdom native Amarna Trust offers an article of the Workmen’s village in said website. Overall, these scholars and many other Egyptian archaeologists above state of the Workmen’s village being important to the study of Amarna from how the villagers live their lives in Pharaoh Akhenaten’s reign in his capital of Akhetaten.

References

- Weatherhead, Fran J. The Main Chapel st the Amarna Workmen's Village and its Wall Paintings. 2077. Print

- Kemp, Barry J. "The Amarna Workmen's Village in Retrospect." Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1987, 73, 21-50 Print.