William Walker (filibuster)

| William Walker | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the Republic of Nicaragua | |

|

In office July 12, 1856 – May 1, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | Patricio Rivas |

| Succeeded by | Máximo Jerez and Tomás Martínez |

| 1st President of the Republic of Sonora | |

|

In office January 21, 1854 – May 8, 1854 | |

| 1st President of the Republic of Lower California | |

|

In office November 3, 1853 – January 21, 1854 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

May 8, 1824 Nashville, Tennessee |

| Died |

September 12, 1860 (aged 36) Trujillo, Honduras |

| Cause of death | firing squad |

| Resting place | Old Trujillo Cemetery, Trujillo, Colón, Honduras |

| Political party | Democratic (Nicaragua) |

| Signature |

|

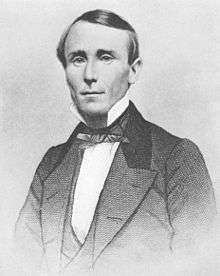

William Walker (May 8, 1824 – September 12, 1860) was an American physician, lawyer, journalist and mercenary who organized several private military expeditions into Latin America, with the intention of establishing English-speaking slave colonies under his personal control, an enterprise then known as "filibustering". Walker usurped the presidency of the Republic of Nicaragua in 1856 and ruled until 1857, when he was defeated by a coalition of Central American armies. He returned in an attempt to reestablish his control of the region and was captured and executed by the government of Honduras in 1860.

Early life

Walker was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824 to James Walker and his wife Mary Norvell. His father was a Scottish immigrant.[1] His mother was the daughter of Lipscomb Norvell, an American Revolutionary War officer from Virginia.[2] One of Walker's maternal uncles was John Norvell, a Senator from Michigan and founder of The Philadelphia Inquirer.[3] William Walker was engaged to Ellen Martin, but she died of yellow fever before they could be married,[4] and he died without children.

William Walker graduated summa cum laude from the University of Nashville at the age of fourteen.[5] He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and University of Heidelberg before receiving his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania at the age of 19. He practiced briefly in Philadelphia before moving to New Orleans to study law.[6]

He practiced law for a short time, then quit to become co-owner and editor of the New Orleans Crescent. In 1849, he moved to San Francisco, where he was a journalist and fought three duels; he was wounded in two of them. Walker then conceived the idea of conquering vast regions of Latin America and creating new slave states to join those already part of the United States.[7] These campaigns were known as filibustering or freebooting.

Duel with William Hicks Graham

William Walker first gained national attention after his duel with William Hicks Graham on January 12, 1851, in San Francisco.[8] Walker was the editor of the San Francisco Herald while Graham was a clerk in the employ of Judge R. N. Morrison. Walker criticized Graham and his colleagues in the newspapers, which angered Graham and prompted him to challenge Walker to a duel.[9] Graham was a notorious gunman and duellist in his time, having taken part in a number of duels and shootouts in the Old West. Walker on the other hand, had experience duelling with single-shot pistols at one time, but his duel with Graham was fought with revolvers.[10]

The combatants met at Mission Dolores and each were given Colt Dragoons with five shots. They stood face-to-face at ten paces, and at the signal of a referee aimed and tried to fire. Graham managed to fire two bullets, hitting Walker in his pantaloons and his thigh, seriously wounding him. Walker, though he tried a number of times to shoot his weapon during the duel, failed to fire even a single shot and Graham was left unscathed. The duel ended when the wounded Walker conceded. Graham was arrested but was quickly released. The duel was recorded in The Daily Alta California.[10]

Expedition to Mexico

In the summer of 1853, Walker traveled to Guaymas, seeking a grant from the government of Mexico to create a colony. He said the colony would serve as a fortified frontier, protecting US soil from Indian raids. Mexico refused, and Walker returned to San Francisco determined to obtain his colony, regardless of Mexico's position.[11]

He began recruiting American supporters of slavery and Manifest Destiny doctrine, mostly inhabitants of Kentucky and Tennessee. His plans then expanded from forming a buffer colony to establishing an independent Republic of Sonora, which might eventually take its place as a part of the American Union as the Republic of Texas had done. He funded his project by "selling scrips which were redeemable in lands of Sonora."[6]

On October 15, 1853, Walker set out with 45 men to conquer the Mexican territories of Baja California Territory and Sonora State. He succeeded in capturing La Paz, the capital of sparsely populated Baja California, which he declared the capital of a new Republic of Lower California, with himself as president and his former law partner, Henry P. Watkins,[12] as vice president. He then put the region under the laws of the American state of Louisiana, which made slavery legal.[12]

Fearful of attacks by Mexico, Walker moved his headquarters twice over the next three months, first to Cabo San Lucas, and then further north to Ensenada to maintain a more secure position of operations, because he lost to General Manuel Márquez de León. Although he never gained control of Sonora, less than three months later, he pronounced Baja California part of the larger Republic of Sonora.[6] Lack of supplies and strong resistance by the Mexican government quickly forced Walker to retreat.[12]

Back in California, he was put on trial for conducting an illegal war, in violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794. Nevertheless, in the era of Manifest Destiny, his filibustering project was popular in the southern and western United States and the jury took eight minutes to acquit him.[13][14]

Conquest of Nicaragua

Since there was no inter-oceanic route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans at the time, and the transcontinental railway did not yet exist, a major trade route between New York City and San Francisco ran through southern Nicaragua. Ships from New York entered the San Juan River from the Atlantic and sailed across Lake Nicaragua. People and goods were then transported by stagecoach across a narrow strip of land near the city of Rivas, before reaching the Pacific and ships to San Francisco. The commercial exploitation of this route had been granted by Nicaragua to the Accessory Transit Company, controlled by shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt.[15]

In 1854, a civil war erupted in Nicaragua between the Legitimist Party (also called the Conservative Party), based in the city of Granada, and the Democratic Party (also called the Liberal Party), based in León. The Democratic Party sought military support from Walker who, to circumvent U.S. neutrality laws, obtained a contract from Democratic president Francisco Castellón to bring as many as three hundred colonists to Nicaragua. These mercenaries received the right to bear arms in the service of the Democratic government. Walker sailed from San Francisco on May 3, 1855, with approximately 60 men. Upon landing, the force was reinforced by 110 locals.[16][17] With Walker's expeditionary force was the well-known explorer and journalist Charles Wilkins Webber as well as the English adventurer Charles Frederick Henningsen, a veteran of the First Carlist War, the Hungarian Revolution, and the war in Circassia.[18]

With Castellón's consent, Walker attacked the Legitimists in the town of Rivas, near the trans-isthmian route. He was driven off, but not without inflicting heavy casualties. In this First Battle of Rivas a school teacher called Enmanuel Mongalo y Rubio (1834–1872) burned the Filibuster headquarters. On September 4, during the Battle of La Virgen, Walker defeated the Legitimist army. On October 13, he conquered the Legitimist capital of Granada and took effective control of the country. Initially, as commander of the army, Walker ruled Nicaragua through provisional President Patricio Rivas.[19] U.S. President Franklin Pierce recognized Walker's regime as the legitimate government of Nicaragua on May 20, 1856.[20] Walker's first ambassadorial appointment, Colonel Parker H. French, was refused recognition.[21]

Walker's actions in the region caused concern in neighboring countries and potential American and European investors who feared he would pursue further military conquests in Central America. C. K. Garrison and Charles Morgan, subordinates of Cornelius Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Company, provided financial and logistical support to the Filibusters in exchange for Walker, as ruler of Nicaragua, seizing the company's property (on the pretext of a charter violation) and turning it over to Garrison and Morgan. Outraged, Vanderbilt dispatched two secret agents to the Costa Rican government with plans to fight Walker. They would help regain control of Vanderbilt's steamboats which had become a logistical lifeline for Walker's army.[22]

Concerned about Walker's intentions in the region, Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras rejected Walker's diplomatic overtures and began preparing the country's military for a potential conflict.[23] Walker organized a battalion of four companies, of which one was composed of Germans, a second of Frenchmen, and the other two of Americans, totaling 240 men placed under the command of Colonel Schlessinger to invade Costa Rica in a preemptive action. This advance force was defeated at the Battle of Santa Rosa on March 20, 1856.

The most important strategic defeat of Walker came during the Campaign of 1856–57 when the Costa Rican army, led by President Juan Rafael Mora Porras, General José Joaquín Mora Porras (the president's brother), and General José María Cañas (1809-1860), defeated the Filibusters in Rivas, Nicaragua on April 11, 1856 (the Second Battle of Rivas).[24] It was in this battle that the soldier and drummer Juan Santamaría sacrificed himself by setting the Filibuster stronghold on fire. In parallel with Enmanuel Mongalo y Rubio in Nicaragua, Santamaría would become Costa Rica's national hero. Walker deliberately contaminated the water wells of Rivas with corpses. Later, a cholera epidemic spread to the Costa Rican troops and the civilian population of the city of Rivas. Within a few months nearly 10,000 civilians had died, almost 10 percent of the population of Costa Rica.[25]

.png)

From the north, President José Santos Guardiola sent Honduran troops under the leadership of the Xatruch brothers, who joined Salvadoran troops to fight Walker. Florencio Xatruch led his troops against Walker and the filibusters in la Puebla, Rivas. Later, because of the opposition of other Central American armies, José Joaquín Mora Porras was made Commandant General-in-Chief of the Allied Armies of Central America in the Third Battle of Rivas (April 1857).

During this civil war, Honduras and El Salvador recognized Xatruch as brigade and division general. On June 12, 1857, Xatruch made a triumphant entrance to Comayagua, which was then the capital of Honduras, after Walker surrendered. The nickname by which Hondurans are known popularly still today, Catracho, and the more infamous nickname Salvadorans are known today, Salvatrucho are derived from Xatruch's figure and successful campaign as leader of the allied armies of Central America, as the troops of El Salvador and Honduras were national heroes, fighting side by side as Central American brothers against William Walker's troops.[26]

As the general and his soldiers returned from battle, some Nicaraguans affectionately yelled out "¡Vienen los xatruches!" ("Here come Xatruch's boys!") However, Nicaraguans had so much trouble pronouncing the general's last name (a northeastern Spanish name, like Guardiola) that they altered the phrase to "los catruches" and ultimately settled on "los catrachos."[27]

A key role was played by the Costa Rican Army in unifying the other Central American armies to fight against Filibusters. The "Campaign of the Transit" (1857), is the name given by Costa Rican historians to the groups of several battles fought by the Costa Rican Army, supervised by Colonel Salvador Mora, and led by Colonel Blanco and Colonel Salazar at the San Juan River. By establishing control of this bi-national river at its border with Nicaragua, Costa Rica prevented military reinforcements from reaching Walker and his Filibuster troops via the Caribbean Sea. Also Costa Rican diplomacy neutralized U.S. official support for Walker by taking advantage of the dispute between the magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt and William Walker.[28]

Walker took up residence in Granada and set himself up as President of Nicaragua, after conducting a fraudulent election. He was inaugurated on July 12, 1856, and soon launched an Americanization program, reinstating slavery, declaring English an official language and reorganizing currency and fiscal policy to encourage immigration from the United States.[30] Realizing that his position was becoming precarious, he sought support from the Southerners in the U.S. by recasting his campaign as a fight to spread the institution of black slavery, which was the basis of the Southern agrarian economy. With this in mind, Walker revoked Nicaragua's emancipation edict of 1821.[31] This move increased Walker's popularity in the South and attracted the attention of Pierre Soulé, an influential New Orleans politician, who campaigned to raise support for Walker's war. Nevertheless, Walker's army was weakened by massive defections and an epidemic of cholera, and was finally defeated by the Central American coalition led by Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras (1814-1860).

On October 12, 1856, Guatemalan Colonel José Víctor Zavala crossed the square of the city to the house where Walker's soldiers took shelter. Under heavy fire, he reached the enemy's flag and carried it back with him, shouting to his men that the Filibuster bullets did not kill.[29]

On December 14, 1856, as Granada was surrounded by 4,000 Costa Rican, Honduran, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan troops, Charles Frederick Henningsen, one of Walker's generals, ordered his men to set the city ablaze before escaping and fighting their way to Lake Nicaragua. When retreating from Granada, the oldest Spanish colonial city in Nicaragua, he left a detachment with orders to level it in order to instill, as he put it, "a salutary dread of American justice". It took them over two weeks to smash, burn and flatten the city; all that remained were inscriptions on the ruins that read "Aqui Fue Granada" ("Here was Granada").[32]

On May 1, 1857, Walker surrendered to Commander Charles Henry Davis of the United States Navy under the pressure of Costa Rica and the Central American armies, and was repatriated. Upon disembarking in New York City, he was greeted as a hero, but he alienated public opinion when he blamed his defeat on the U.S. Navy. Within six months, he set off on another expedition, but he was arrested by the U.S. Navy Home Squadron under the command of Commodore Hiram Paulding and once again returned to the U.S. amid considerable public controversy over the legality of the navy's actions.[33]

Death in Honduras

After writing an account of his Central American campaign (published in 1860 as War in Nicaragua), Walker once again returned to the region. British colonists in Roatán, in the Bay Islands, fearing that the government of Honduras would move to assert its control over them, approached Walker with an offer to help him in establishing a separate, English-speaking government over the islands. Walker disembarked in the port city of Trujillo, but soon fell into the custody of Commander Nowell Salmon (later Admiral Sir Nowell Salmon) of the British Royal Navy. The British government controlled the neighboring regions of British Honduras (now Belize) and the Mosquito Coast (now part of Nicaragua) and had considerable strategic and economic interest in the construction of an inter-oceanic canal through Central America. It therefore regarded Walker as a menace to its own affairs in the region.[34]

Rather than return him to the US, for reasons that remain unclear, Salmon sailed to Trujillo and delivered Walker to the Honduran authorities, together with his chief of staff, Colonel A. F. Rudler. Rudler was sentenced to four years in the mines, but Walker was sentenced to death, and executed by firing squad, near the site of the present-day hospital, on September 12, 1860.[35] William Walker was 36 years old. He is buried in the "Old Cemetery", Trujillo, Colón, Honduras.

Influence and reputation

William Walker convinced many Southerners of the desirability of creating a slave-holding empire in tropical Latin America. In 1861, when U.S. Senator John J. Crittenden proposed that the 36°30' parallel north be declared as a line of demarcation between free and slave territories, some Republicans denounced such an arrangement, saying that it "would amount to a perpetual covenant of war against every people, tribe, and State owning a foot of land between here and Tierra del Fuego."[36]

Before the end of the American Civil War, Walker's memory enjoyed great popularity in the southern and western United States, where he was known as "General Walker"[37] and as the "gray-eyed man of destiny".[5] Northerners, on the other hand, generally regarded him as a pirate. Despite his intelligence and personal charm, Walker consistently proved to be a limited military and political leader. Unlike men of similar ambition, such as Cecil Rhodes, Walker's grandiose scheming ultimately failed against the union of Central American people.

In Central American countries, the successful military campaign of 1856–1857 against William Walker became a source of national pride and identity,[38] and it was later promoted by local historians and politicians as substitute for the war of independence that Central America had not experienced. April 11 is a Costa Rican national holiday in memory of Walker's defeat at Rivas. Juan Santamaría, who played a key role in that battle, is honored as one of two Costa Rican national heroes, the other one being Juan Rafael Mora himself. The main airport serving San José (in Alajuela) is named in Santamaría's honor.

Cultural references

.jpg)

Walker's campaign has inspired two films, both of which take considerable liberties with his story: Burn! (1969) directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, starring Marlon Brando, and Walker (1987) directed by Alex Cox, starring Ed Harris. Walker's name is used for the main character in Burn!, though the character is not meant to represent the historical William Walker and is portrayed as British.[39] On the other hand, Alex Cox's Walker incorporates into its surrealist narrative many of the signposts of William Walker's life and exploits, including his original excursions into northern Mexico to his trial and acquittal on breaking the neutrality act to the triumph of his assault on Nicaragua and his execution.[40]

In Part Five, Chapter 48, of Gone with the Wind, Margaret Mitchell cites William Walker, "and how he died against a wall in Truxillo", as a topic of conversation between Rhett Butler and his filibustering acquaintances, while Rhett and Scarlett are on honeymoon in New Orleans.[41]

A long early poem by the Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal, Con Walker En Nicaragua, translated as With Walker in Nicaragua,[42] gives a historical treatment of the affair.

Nate DiMeo's historical podcast The Memory Palace featured an episode on William Walker entitled "Presidente Walker".[43]

William Walker is a little-known figure in American history, evidenced in 1988 when President George H.W. Bush selected a new ambassador for El Salvador to ease tensions following the Central American crisis, whose name was, by chance, William Walker.[44]

Works

- Walker, William. The War in Nicaragua. New York: S.H. Goetzel, 1860.

See also

- Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon

- Golden Circle (proposed country)

- Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret society interested in annexing territories in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean to be added to the United States as slave states

- Nicaragua Canal

- Panama Canal

Notes

- ↑ Scroggs, p. 9.

- ↑ Coke, Fletch (2017). "Lipscomb Norvell, September 1756 – March 2, 1843" (PDF). Nashville City Cemetery. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ↑ Michigan Historical Commission. (1924). Michigan biographies, including members of Congress, elective state officers, justices of the Supreme court. Vol. II. Lansing: The Michigan historical commission. pp. 151–2.

- ↑ Scroggs, p. 14.

- 1 2 Norvell, John E. (Spring 2012). "How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857" (PDF). Middle Tennessee Journal of Genealogy & History. XXV (4): 149–155. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Juda, Miss Fanny (February 1919). "California Filibusters: A History of their Expeditions into Hispanic America". The Grizzly Bear. Native Sons and Native Daughters of the Golden West. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 114

- ↑ Thrapp, Dan L. Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: G-O. University of Nebraska Pr; Auflage: Reprint (August 1991). p. 578. ISBN 978-0803294196

- ↑ Rosa, Joseph G. Age of the Gunfighter: Men and Weapons on the Frontier, 1840-1900. University of Oklahoma Press; 1st edition (September 15, 1995) p. 27. ISBN 978-0806127613

- 1 2 Chamberlain, Ryan. Pistols, Politics and the Press: Dueling in 19th Century American Journalism. McFarland (December 10, 2008). p. 92. ISBN 978-0786438297

- ↑ Scroggs, pp. 31–33.

- 1 2 3 Soodalter, Ron (March 4, 2010). "William Walker: King of the 19th Century Filibusters". HistoryNet. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ↑ Scroggs, pg 65

- ↑ "The Biography of William Walker". Latinamericanhistory.about.com. March 7, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Finch, Richard C. "William Walker". The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Scroggs, pg 108

- ↑ Walker, pg 42

- ↑ Scroggs, pg 7

- ↑ Scroggs, pg 150

- ↑ McPherson pg 112

- ↑ Scroggs, pg 141

- ↑ Scroggs, pg 270-1

- ↑ Quesada, Juan Rafael (2007). "La Guerra Contra los Filibusteros y la Nacionalidad Costarricense" (PDF). Revista Estudios (in Spanish). University of Costa Rica (20): 61–79. ISSN 1659-1925. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Scroggs, pg 188

- ↑ Mata, Leonardo (February 1992). "El Cólera en la Costa Rica en 1856" (PDF). Revista Nacional de Cultura (in Spanish): 55–60. ISSN 1013-9060. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Sánchez Ramírez, Roberto. "El general que trajo a los primeros catrachos". La Prensa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 10 November 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- ↑ Sánchez Ramírez, Roberto. "El general que trajo a los primeros catrachos". La Prensa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2007-11-10. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ↑ Arias, Raúl (2010). "Juan Rafael Mora y las tres fases de la Campaña Nacional" (PDF). Revista Comunicación. Cartago, Costa Rica: Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica. 19: 60–68. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- 1 2 Dueñas Van Severen 2006, p. 140.

- ↑ Scroggs, pp. 201–208.

- ↑ Scroggs, pp. 211–213.

- ↑ Theodore Henry Hittell, History of California (N.J. Stone, 1898), p. 797

- ↑ Scroggs, pp. 333–6

- ↑ Scroggs, pp. 72–4

- ↑ "Maps of Nicaragua, North and Central America: Population and Square Miles of Nicaragua, United States, Mexico, British and Central America, with Routes and Distances; Portraits of General Walker, Colonel Kinney, Parker H. French, and Views of the Battle of New-Orleans and Bunker Hill". World Digital Library. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle cry of freedom: the Civil War era. US: Oxford University Press. pp. 904 pages. ISBN 0-19-516895-X.

- ↑ Scroggs, p. 226.

- ↑ Tirmenstein, Lisa (May 14, 2014). "Costa Rica in 1856: Defeating William Walker While Creating a National Identity". Miami University. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ↑ McKinney, Mac (18 January 2011). "Life Imitating Art in Haiti? Pontecorvo's Movie Queimada (Burn!) as Presage for What May Go Down Next". OpEdNews. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Grove, Lloyd. "Hollywood Invades Nicaragua". The Washington Post, August 20, 1987.

- ↑ Mitchell, Margaret. "Chapter 48". Gone With the Wind.

- ↑ With Walker in Nicaragua and Other Early Poems, 1949–1954, translated by Jonathan Cohen, Wesleyan University Press, 1985

- ↑ DiMeo, Nate (16 June 2009). "Episode 15: Presidente Walker". WordPress. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20080131135251/http://www.handofhope.org/board/walker.html

References

Secondary sources

- Carr, Albert Z. The World and William Walker, 1963.

- Dando-Collins, Stephen. Tycoon's War: How Cornelius Vanderbilt Invaded a Country to Overthrow America's Most Famous Military Adventurer (2008) excerpt and text search

- Dueñas Van Severen, J. Ricardo (2006). La invasión filibustera de Nicaragua y la Guerra Nacional (in Spanish). Secretaría General del Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana SG-SICA.

- Juda, Fanny. California Filibusters: A History of their Expeditions into Hispanic America

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 909. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- May, Robert E. Manifest Destiny's Underworld: Filibustering in Antebellum America, 2002.

- May, Robert E. The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

- Moore, J. Preston. "Pierre Soule: Southern Expansionist and Promoter," Journal of Southern History 21:2 (May, 1955), 208 & 214.

- Norvell, John Edward, "How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857: The Norvell Family origins of the Grey Eyed Man of Destiny," The Middle Tennessee Journal of Genealogy and History, Vol XXV, No.4, Spring 2012

- "1855: American Conquistador," American Heritage, October 2005.

- Recko, Corey. "Murder on the White Sands." University of North Texas Press. 2007

- Scroggs, William O. (1916). Filibusters and Financiers; the story of William Walker and his associates. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- "William Walker" Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 28 Oct. 2008.

Primary sources

- Doubleday, C.W. Reminiscences of the Filibuster War in Nicaragua. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1886.

- Jamison, James Carson. With Walker in Nicaragua: Reminiscences of an Officer of the American Phalanx. Columbia, MO: E.W. Stephens, 1909.

- Wight, Samuel F. Adventures in California and Nicaragua: a Truthful Epic. Boston: Alfred Mudge & Son, 1860.

- Fayssoux Collection. Tulane University. Latin American Library.

- United States Magazine. Sept., 1856. Vol III No. 3. pp. 266–72

- "Filibustering", Putnam's Monthly Magazine (New York), April 1857, 425–35.

- "Walker's Reverses in Nicaragua," Anti-Slavery Bugle, November 17, 1856.

- "The Lesson" National Era, June 4, 1857, 90.

- "The Administration and Commodore Paulding," National Era, January 7, 1858.

- "Wanted – A Few Filibusters," Harper's Weekly, January 10, 1857.

- "Reception of Gen. Walker," New Orleans Picayune, May 28, 1857.

- "Arrival of Walker," New Orleans Picayune, May 28, 1857.

- "Our Influence in the Isthmus," New Orleans Picayune, February 17, 1856.

- New Orleans Sunday Delta, June 27, 1856.

- "Nicaragua and President Walker," Louisville Times, December 13, 1856.

- "Le Nicaragua et les Filibustiers," Opelousas Courier, May 10, 1856.

- "What is to Become of Nicaragua?," Harper's Weekly, June 6, 1857.

- "The Late General Walker," Harper's Weekly, October 13, 1860.

- "What General Walker is Like," Harper's Weekly, September, 1856.

- "Message of the President to the Senate in Reference to the Late Arrest of Gen. Walker," Louisville Courier, January 12, 1858.

- "The Central American Question – What Walker May Do," New York Times, January 1, 1856.

- "A Serious Farce," New York Times, December 14, 1853.

- 1856–57 New York Herald Horace Greeley editorials.

Further reading

- Harrison, Brady. William Walker and the Imperial Self in American Literature. University of Georgia Press, August 2, 2004. ISBN 0-8203-2544-9. ISBN 978-0-8203-2544-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Walker. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1900 Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography article about William Walker. |

- "Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt fought war over route through Central America" from the Vanderbilt Register

- "Walker's expeditions" from GlobalSecurity.org

- "Filibustering with William Walker" from the Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- Fuchik, Don "The Saga of William Walker" The California Native Newsletter

- Walker the 1987 Alex Cox movie, Walker, featuring Ed Harris as William Walker, at the Internet Movie Database

- Patrick Deville, Pura Vida: Vie et mort de William Walker, Seuil, Paris,2004

- "How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857 The Norvell family origins of The Grey Eyed Man of Destiny"

- the memory palace podcast episode about William Walker.

- Walker, William "The War in Nicaragua" at Google Books

- Brief recount of William Walker trying to conquer Baja California (in Spanish)

- With Walker in Nicaragua by Ernesto Cardenal, translated by Jonathan Cohen

- Maps of North America and the Caribbean showing Walker's expeditions at omniatlas.com