Maryvale, Phoenix

| Maryvale | |

|---|---|

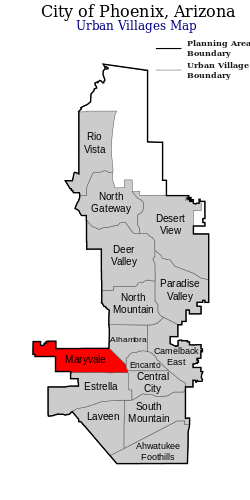

| Urban Village of Phoenix | |

Maryvale Urban Village within Phoenix. | |

Maryvale Baseball Park and surrounding suburban development. | |

| Coordinates: 33°30′07″N 112°10′40″W / 33.50194°N 112.17778°WCoordinates: 33°30′07″N 112°10′40″W / 33.50194°N 112.17778°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| City | Phoenix |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 37.6 sq mi (~97.4 km2) |

| Elevation[2] | 1,119 ft (341 m) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • Total | 208,189 |

| • Density | 6,500/sq mi (4,000/km2) |

| Area code(s) | 602 623 |

| Website | Maryvale Village Planning Committee |

Maryvale is an urban village[4] of Phoenix, Arizona.

History

Plans for Maryvale began to take shape during the 1950s, when developer John F. Long came up with the idea of developing a master-planned community on the western part of Phoenix,[5] with an aim of turning the area into a working class suburb for Caucasians.[6] It was the first master planned community in Arizona,[7] and one of the first planned communities in the country.[6] The community was designed to include space for parks, schools, and space to fulfill other community service requirements.[8]

The community was named after Long's wife, Mary,[5] and its initial master plan was drawn up by Victor Gruen.[5] By 1956, Long was selling 125 homes a week in Maryvale.[6]

Demographic changes came to the area by 1975, as residents in the area began to move north.[9] Meanwhile, Hispanic families began moving into the area in the 1980s.[9] The discovery of a cancer cluster in the 1980s (see below) reportedly contributed to white flight in the community.[10]

In the 1990s, the community is noted for having a crime problem.[11] Gangs moved into condominiums and apartment complexes in the area, and were not afraid of challenging law enforcement.[11] Gang members at one particular condominium, Woodmar, was noted to have threatened law enforcement officials, to the extent that Phoenix Police did not allow its officers to enter the condominium, without the backup of at least two other police officers.[11] The area also had a problem with graffiti.[12]

In 1999, Phoenix Police Department officer Marc Atkinson was shot and killed in Maryvale, in the first fatal shooting of a police officer in the city since 1991.[11] In that same year, Phoenix Police began an effort aimed at reducing crime at the Woodmar, with search warrants served, drug and criminal syndicate charges filed against individuals, and restraining orders served on people who do not live at the complex.[13] As a result, there was a decrease in crime at the complex.[13]

As recently as 2016, however, the community is still experiencing crime problems.[14] The community was also rocked by a number of shootings that were allegedly committed by the Serial Street Shooter in 2016.[15] At the time, community leaders expressed concerns that the community has been ignored by city leaders and the city's police.[15]

Maryvale made local, national, and international headlines in 2014, after reports surfaced of feral chihuahuas terrorizing area residents.[16][17][18] Its veracity, however, has been challenged by the Phoenix New Times.[19]

Geography

The community is located on the western edge of the City of Phoenix, and encompasses an area southwest of Grand Avenue, east of the Interstate 17, north of McDowell Road and Interstate 10, and east and southeast of the city limits of Phoenix.[1]

Demographics

Maryvale is the most populous of the Phoenix's urban villages.[20]

As of 2010, the Urban Village of Maryvale had a population of 208,189.[3] While census figures show no single ethnic group being in the majority, Caucasians whites made up the largest single racial group, comprising 49.5% of the community's population.[3] 37% of the community's population are identified as members of "Some Other Race".[3] 6% of the population are Blacks or African Americans, followed by American Indian or Alaska Native (1.9%), Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islanders (1.9%), and Asian (1.5%).[3]

76% of the community's residents are identified as "Hispanics".[21][3] This makes the village a minority-majority community.[9]

The median household income in Maryvale is $40,504/year, and 20.63% of the community's population live under the poverty line.[3]

Arts and culture

Maryvale is home to Ak-Chin Pavilion, an entertainment venue for the Phoenix metropolitan area.[22]

Sports and recreation

Baseball

Maryvale Baseball Park, a 56 acres (23 ha) facility built in 1998, is the spring training home for the Milwaukee Brewers.[23][24]

In November 2017, the Phoenix City Council approved a deal that will keep the Brewers at the facility for another 25 years. In exchange, the city will contribute $2 million per year, for five years, towards park renovation efforts.[25]

Camelback Ranch, a 141 acres (57 ha) facility,[26] is located within the community,[24] and is the spring training home for the Los Angeles Dodgers and Chicago White Sox.[26]

Golf

The City of Phoenix once operated the Maryvale Golf Course, a championship-length golf course that was designed by William F. Bell, who also designed the Torrey Pines Golf Course in San Diego, California.[27] The 130 acres (53 ha) facility[28] opened in 1961,[5] but the City of Phoenix eventually ran the golf course at a loss of $250,000 per year.[29] The golf course reopened as the Grand Canyon University Golf Course on January 6, 2016, as a partnership between the City of Phoenix and Grand Canyon University.[29] The new golf course was redesigned by John Fought,[29] with a rebuilt clubhouse.[28] GCU, which invested $10 million into the project, will split the golf course's profits with the City of Phoenix, after it recoups its initial investment.[29]

Infrastructure

Transportation

The Desert Sky Transit Center, which opened for service in December 2015, serves public transit users in the area.[30] A number of Valley Metro bus routes call at the station,[30] including the Bus Rapid Transit route I-10 West RAPID, which carries passengers from the center to Downtown Phoenix,[31] and the Phoenix/Gila Bend Regional Connector, which carries passengers between the transit center and Gila Bend.[32]

The community is also served by a local circulator bus route called Phoenix Neighborhood Circulator MARY.[33]

Health

In 2011, non-profit community health center group Mountain Health Center converted an abandoned theater in Maryvale into a clinic.[34]

In December 2017, Abrazo Community Health Network closed its campus in Maryvale, citing declining demands for its services.[35] The decision to close the hospital was announced in October of that year, and although officials with Abrazo said the closure would not impact the community's access to healthcare,[35] residents were concerned that the extra time spent traveling to other healthcare facilities nearby could be detrimental during an emergency situation.[36] In 2018, Maricopa Integrated Health System announced it will reopen the hospital, along with its emergency department, in 2019. The hospital will reopen as a behavioral health hospital.[37]

Environment

The area was noted as being built on farmland that saw heavy pesticide use, at a time when DDT was in regular use.[6] Maryvale is also the site of a state Superfund site known as the West Central Phoenix Water Quality Assurance Revolving Fund (WQARF) site, due to the dumping of chemicals, including TCE, by a number of industries in the area.[6]

The West Central Phoenix WQARF, according to the state's Department of Environmental Quality, is an area that contains five plumes of groundwater contamination, involving Volatile organic compound, PCE, and TCE.[38] The water under the area is not used in the public drinking water system.[38]

Cancer cluster

In 1987, residents in the area became aware of the fact that Maryvale was part of a cancer cluster.[39] From 1970 to 1986, newborns to 19-year-olds died of Leukemia at a rate that was twice the national average at the time.[39] In addition, a study that began in 1983 and released in 1987 revealed that in the same general area of the cancer cluster, elevated rates of birth defects were identified.[40]

The state's Department of Health Services was reportedly aware of the cancer cluster problem at least five years prior, and repeatedly refused to launch a substantive investigation.[39] In addition, the agency also told the principal of a parochial school in the area who first discovered that children were dying to not talk about the issue.[41]

A study was later launched by the state, with an original completion deadline of 1991.[42] The study, under the oversight of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[41] faced a number of delays,[41] and eventually found no link between environmental factors and the leukemia cases.[41] Critics accuse the ADHS for not looking seriously at the community's water supply, instead focusing on collecting data on a myriad of variables.[41] Some critics also leveled accusations that the study was drawn out, with the intention of deflecting litigation against the city, as well as polluting industries.[41] As recently as 2009, the state's Department of Environmental Quality maintains there is no link between Maryvale's groundwater contamination, and increased cancer rates.[43]

Notable residents

- Henry Cejudo, wrestler; won gold medal at 2008 Beijing Olympics[9]

- Doug Mathis, professional baseball pitcher[44]

- Sandra Day O'Connor, first female justice of the United States Supreme Court[45]

- CeCe Peniston, R&B singer[9]

- Phillippi Sparks, NFL player[46]

- Darren Woodson, NFL player[9]

References

- 1 2 "Maryvale Village Brochure" (PDF). City of Phoenix. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ "Feature Detail Report for: Maryvale". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Maryvale Village" (PDF). City of Phoenix. 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ "Villages". City of Phoenix. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Godfrey, William (2010). Maryvale Golf Course: The First 50 Years. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ross, Andrew (2011). Bird on Fire: Lessons from the World's Least Sustainable City. Oxford University Press. pp. 128–131. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "John F. Long". The Arizona Republic. March 9, 2008. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ↑ "John F. Long". Historical League, Inc. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lang, Erica (17 December 2015). "In one West Valley community, ever-shifting demographics are changing the face of Phoenix". The Arizona Republic. Cronkite News Service. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "A planet of suburbs". The Economist. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Farnsworth, Chris (24 June 1999). "Crackdown". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Holmstrom, David (14 February 1996). "No More Handwriting On This Community's Wall". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- 1 2 "Woodmar Revitalization Project" (PDF). Center for Problem-Oriented Policing. City of Phoenix. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Dana, Joe (22 February 2016). "Increase in crime an issue in Maryvale". KPNX. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- 1 2 Escárcega, Patricia (5 October 2016). "Maryvale 'Serial Shooter' Murders Have Residents on Edge — And Feeling Abandoned". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ Krafft, Steve (13 February 2014). "Dogs gone wild; packs of Chihuahuas roam Maryvale streets". KSAZ-TV. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Grossman, Samantha (18 February 2014). "Ragtag Team of Rogue Chihuahuas Terrorizing Arizona Town". Time Magazine. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Saul, Heather (21 February 2014). "Packs of stray Chihuahuas chase children and terrorise residents in Arizona suburb". The Independent. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Hendley, Matthew (18 February 2014). "Gangs of Chihuahuas Are Not Running Maryvale". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "2010 Census Characteristics for all Villages + Phoenix" (PDF). City of Phoenix. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ See Hispanic–Latino naming dispute for details of an ongoing dispute on the naming of US inhabitants who are of Latin American or Spanish origin.

- ↑ "Maryvale Village Character Plan" (PDF). City of Phoenix. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ "Maryvale Baseball Park". City of Phoenix. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- 1 2 "Maryvale". City of Phoenix. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

...the Village is home to two major league baseball spring training facilities. One is located at 51st Avenue and Indian School Road and the other is located at 107th Avenue and Camelback Road.

- ↑ "Phoenix lawmakers vote to keep Milwaukee Brewers in Maryvale". KTAR-FM. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- 1 2 "About Camelback Ranch". Camelback Ranch. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ "Maryvale Golf Course". City of Phoenix. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- 1 2 Goth, Brenna (11 December 2015). "5 facts about the Grand Canyon University golf course in west Phoenix". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Obert, Richard (6 January 2016). "GCU Golf Course at old Maryvale site now open". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- 1 2 "New Desert Sky Transit Center Nears Completion". City of Phoenix. 25 November 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ "I-10 West RAPID". Valley Metro. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ "Phoenix/Gila Bend Regional Connector". Valley Metro. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ "Phoenix Neighborhood Circulator MARY". Valley Metro. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ "Maryvale". Mountain Park Health Center. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- 1 2 Ciletti, Nick (18 December 2017). "Abrazo closes the doors to Maryvale hospital". KNXV-TV. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Carlson, Kara (20 October 2017). "Maryvale residents express concerns about hospital closure". Cronkite News. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "Closed Maryvale hospital to reopen in 2019". KSAZ-TV. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- 1 2 "West Central Phoenix Water Quality Assurance Revolving Fund Site" (PDF). Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Greene, Terry (22 February 1989). "Piercing Together The West-side Cancer Cluster". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "Performance audit, Department of Health Services, Division of Disease Prevention". Arizona Memory Project. State of Arizona Research Library. May 1989. p. 18. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Downing, Renée (12 February 2004). "Cancer Wars". Tucson Weekly. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Sterling, Terry Greene (24 October 1996). "The Pain of Maryvale". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "Community Involvement Plan" (PDF). Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. p. 17. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "Doug Mathis". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Profile: Justice Sandra Day O'Connor". PBS NewsHour. 1 July 2005. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Obert, Richard (9 September 2015). "Maryvale High's all-time greatest football players". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 24 January 2018.