MASH (film)

| MASH | |

|---|---|

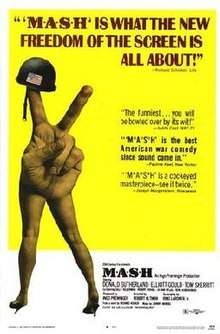

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Altman |

| Produced by | Ingo Preminger |

| Screenplay by | Ring Lardner Jr. |

| Based on |

MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors by Richard Hooker |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Johnny Mandel |

| Cinematography | Harold E. Stine |

| Edited by | Danford B. Greene |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.025 million[1] |

| Box office | $81.6 million[2] |

MASH (stylized as M*A*S*H on the poster art) is a 1970 American satirical black comedy war film directed by Robert Altman and written by Ring Lardner Jr., based on Richard Hooker's novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors. The picture is the only theatrically released feature film in the M*A*S*H franchise, and it became one of the biggest films of the early 1970s for 20th Century Fox.

The film depicts a unit of medical personnel stationed at a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) during the Korean War; the subtext is about the Vietnam War.[3] It stars Donald Sutherland, Tom Skerritt, and Elliott Gould, with Sally Kellerman, Robert Duvall, René Auberjonois, Gary Burghoff, Roger Bowen, Michael Murphy, and in his film debut, professional football player Fred Williamson.

The film won Grand Prix du Festival International du Film, later named Palme d'Or, at 1970 Cannes Film Festival. The film went on to receive five Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, and won for Best Adapted Screenplay. MASH was deemed "culturally significant" by the Library of Congress and was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. The Academy Film Archive preserved MASH in 2000.[4] The film inspired the television series M*A*S*H, which ran from 1972 to 1983.

Plot

In 1951, the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in South Korea is assigned two new surgeons, "Hawkeye" Pierce and "Duke" Forrest, who arrive in a stolen Army Jeep. They are insubordinate, womanizing, mischievous rule-breakers, but they soon prove to be excellent combat surgeons. Other characters already stationed at the camp include bumbling commanding officer Henry Blake, his hyper-competent chief clerk Radar O'Reilly, dentist Walter "Painless Pole" Waldowski, the incompetent and pompous surgeon Frank Burns, and the contemplative Chaplain Father Mulcahy.

The main characters in the camp divide into two factions. Irritated by Burns' religious fervor, Hawkeye and Duke get Blake to move him to another tent so newly arrived chest surgeon Trapper John McIntyre can move in. The three doctors (the "Swampmen," after the nickname for their tent) have little respect for military protocol, having been drafted into the Army, and are prone to pranks, womanizing, and heavy drinking. Burns is a straitlaced military officer who wants everything done efficiently and by the book, as is Margaret Houlihan, who has been assigned to the 4077th as head nurse. The two bond over their respect for regulations and start a secret romance. With help from Radar, the Swampmen sneak a microphone into a tent where the couple are making love and broadcast their affair over the camp's PA system, embarrassing them badly. The next morning, Hawkeye goads Burns into assaulting him, resulting in Burns' removal from the camp for psychiatric evaluation. Later, the Swampmen humiliate Houlihan again by pulling up the walls of the shower tent while she is inside, exposing her naked body for all to see.

Painless, described variously as "the best-equipped dentist in the Army" and "the dental Don Juan of Detroit," becomes depressed over an incident of impotence and announces his intention to commit suicide. The Swampmen agree to help him carry out the deed, staging a feast reminiscent of the Last Supper, arranging for Father Mulcahy to give Painless the last rites, and providing him with a "black capsule" to speed him on his way. Hawkeye persuades the gorgeous Lieutenant "Dish" Schneider, who is being transferred back to the United States for discharge, to spend the night with Painless to cure his temporary impotence. The next morning, Painless is his usual cheerful self, and a smiling Dish leaves camp in a helicopter to start her journey home.

Trapper and Hawkeye are sent to Japan on temporary duty to operate on a Congressman's son. When they later perform an unauthorized operation on a local infant, they face disciplinary action from the hospital commander for misusing Army resources. Using staged photographs of him in bed with a prostitute, they blackmail him into keeping his mouth shut.

Following their return to camp, Blake and General Hammond organize a game of football between the 4077th and the 325th Evac Hospital and wager several thousand dollars on its outcome. At Hawkeye's suggestion, Blake applies to have a specific neurosurgeon–Dr. Oliver Harmon Jones, a former professional football player for the San Francisco 49ers–transferred to the 4077th as a ringer. Blake bets half his money up front, keeping Jones out of the first half of the game. The 325th scores repeatedly and easily, even after the 4077th drugs one of their star players to incapacitate him, and Hammond confidently offers high odds against which Blake bets the rest of his money. Jones enters the second half, which quickly devolves into a free-for-all, and the 4077th gets the 325th's ringer thrown out of the game and wins with one last trick play.

Not long after the football game, Hawkeye and Duke get their discharge orders and begin their journey home–taking the same stolen Jeep in which they arrived.

Cast

- Donald Sutherland as Capt. Benjamin Franklin "Hawkeye" Pierce Jr.

- Elliott Gould as Capt. John Francis Xavier "Trapper John" McIntyre

- Tom Skerritt as Capt. Augustus Bedford "Duke" Forrest

- Sally Kellerman as Major Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan

- Robert Duvall as Major Frank Burns

- Roger Bowen as Lt. Col. Henry Braymore Blake

- René Auberjonois as Father Francis John Patrick "Dago Red" Mulcahy

- David Arkin as SSgt. Wade Douglas Vollmer

- Jo Ann Pflug as Lt. Maria "Dish" Schneider

- John Schuck as Capt. Walter Kosciuszko "The Painless Pole" Waldowski, DDS

- Carl Gottlieb as Capt. John "Ugly John" Black

- Danny Goldman as Capt. Dennis Murrhardt

- Corey Fischer as Capt. Patrick "Band-Aid" Bandini

- Indus Arthur as Lt. Leslie

- Dawne Damon as Lt. Wilma "Scorch" Storch

- Tamara Horrocks as Capt. Bridget "Knocko" McCarthy

- Gary Burghoff as Cpl. "Radar" O'Reilly

- Ken Prymus as Pfc. Seidman

- Fred Williamson as Capt. Oliver Harmon "Spearchucker" Jones

- Michael Murphy as Capt. Ezekiel Bradbury "Me Lay" Marston V

- Timothy Brown as Cpl. Judson

- Bud Cort as Pvt. Warren Boone

- G. Wood as Brig. Gen. Charlie Hammond

- Kim Atwood as Ho-Jon

- Dale Ishimoto as Korean doctor

- Bobby Troup as Sgt. Gorman

- Marvin Miller as PA announcer

- Sylvester Stallone as Soldier (uncredited)

Production

Development

The screenplay, by Ring Lardner, Jr., is different from the original novel. In the DVD audio commentary, Altman describes the novel as "pretty terrible" and somewhat "racist" (the only major black character has the nickname "Spearchucker"). He claims that the screenplay was used only as a springboard. While some improvisation occurs in the film and Altman changed the order of major sequences, most sequences are in the novel. The main deletion is a subplot of Ho-Jon's return to the 4077th as a casualty (when Radar steals blood from Henry, it is for Ho-Jon's operation under Trapper and Hawkeye's scalpels; when the surgeons are playing poker after the football game, they are resolutely ignoring Ho-Jon's corpse being driven away). The main deviation from the script is the trimming of much of the dialogue. According to Altman, Lardner was very upset with the liberties taken with his script, although Lardner denied this in his autobiography.

The filming process was difficult because of tensions between the director and his cast. During principal photography, Sutherland and Gould allegedly spent a third of their time trying to get Altman fired,[5] although this has been disputed.[6] Altman, relatively new to the filmmaking establishment at that time, lacked the credentials to justify his unorthodox filmmaking process and had a history of turning down work rather than creating a poor-quality product.[7] Altman: "I had practice working for people who don't care about quality, and I learned how to sneak it in."[8] Altman later commented that if he had known about Gould and Sutherland's protests, he would have resigned.[9] Gould later sent a letter of apology, and Altman used him in some of his later works, but he never worked with Sutherland again.

Only a few loudspeaker announcements were used in the original cut. When Altman realized he needed more structure to his largely episodic film, editor Danford Greene suggested using more loudspeaker announcements to frame different episodes of the story. Greene took a second-unit crew and filmed additional shots of the speakers. On the same night these scenes were shot, American astronauts landed on the moon.[10]

During production, a caption that mentions the Korean setting was added to the beginning of the film,[11] at the request of 20th Century Fox studios.[12] The Korean War is explicitly referenced in announcements on the camp public address system[13] and during a radio announcement that plays while Hawkeye and Trapper are putting in Col. Merrill's office which also cites the film as taking place in 1951.

In his director's commentary on the DVD release, Altman says that M*A*S*H was the first major studio film to use the word "fuck" in its dialogue.[14] The word is spoken during the football game near the end of the film by "the Painless Pole" when he says to an opposing football player, "All right, Bud, your fucking head is coming right off!" The actor, John Schuck, said in an interview that Andy Sidaris, who was handling the football sequences, encouraged Shuck to "say something that’ll annoy him." Shuck did so, and that particular statement made it into the film without a second thought.[15] However, Altman is mistaken. The first audible use of the word "fuck" as part of the dialogue in a movie occurred in the film Ulysses in 1967.[16]

Music

Johnny Mandel composed incidental music used throughout the film. Also heard on the soundtrack are Japanese vocal renditions of such songs as "Tokyo Shoe Shine Boy", "My Blue Heaven", "Happy Days Are Here Again", "Chattanooga Choo Choo", and "Hi-Lili, Hi-Lo"; impromptu performances of "Onward, Christian Soldiers", "When the Lights Go On Again", and "Hail to the Chief" by cast members; and the instrumental "Washington Post March" during the climactic football game. Columbia Records issued a soundtrack album for the film in 1970.

M*A*S*H features the song "Suicide Is Painless", with music by Mandel and lyrics by Mike Altman, the director's then 14-year-old son. The version heard under the opening credits was sung by uncredited session vocalists John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ron Hicklin, and Ian Freebairn-Smith (on the single release, the song is attributed to "The Mash"); the song is reprised later in the film by Pvt. Seidman (played by Ken Prymus) in the scene in which the Painless Pole attempts to commit suicide. Altman has noted in interviews that his son made quite a bit more money off publishing royalties for the song than the $70,000 or so he was paid to direct the film.

Reception

It was the sixth most popular film at the French box office in 1970.[17]

Critical response

M*A*S*H received mostly positive reviews from critics. The film currently holds an 85% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 47 reviews, with an average rating of 8.4/10. The website's consensus states, "Bold, timely, subversive, and above all, funny, M*A*S*H remains a high point in Robert Altman's distinguished filmography."[18] The film also holds a score of 79 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on 7 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews."[19]

Accolades

M*A*S*H won the Palme d'Or at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival.[20] It was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture (lost to Patton), Best Director (lost to Patton), Best Supporting Actress for Sally Kellerman (lost to Helen Hayes for Airport), and Best Film Editing (lost to Patton), and won an Oscar for its screenplay. The film also won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy) in 1971. It was the 38th film to be released to the home video market when 20th Century Fox licensed 50 motion pictures from their library to Magnetic Video. In 1996, M*A*S*H was deemed "culturally significant" by the Library of Congress and was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. The film is number 17 on Bravo's "100 Funniest Movies" and number 54 on "AFI" list of the top 100 American movies of all time.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 1998: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – #56[21]

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #7[22]

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Suicide Is Painless" – #66[23]

- 2007: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #54[24]

Home media

The film was re-released in North America in 1973, and earned an estimated $3.5 million in rentals. To attract audiences to the M*A*S*H television series, which was struggling with audiences at the time, the film was re-released at 112 minutes and received a PG rating. Several scenes were edited, including segments of graphic operations, the word "fuck" in the football game, and the scene where the curtain in the shower is pulled up on Hot Lips. "Suicide is Painless", the film's main theme song was replaced with music by Ahmad Jamal, according to film critic and historian Leonard Maltin in his movie and video guide. In the 1990s, Fox Video released a VHS version of M*A*S*H under their "Selections" banner which ran 116 minutes and rated PG. However, this is not the alternate PG version which was released in 1973. It has the same run time as the theatrical release; none of the aforementioned scenes or theme music was removed. The actual 1973 PG-edited version has never been released on video in the United States.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Solomon, Aubrey. Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1. p. 256.

- ↑ "M*A*S*H, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ↑ The Entertainment Weekly Guide to the Greatest Movies Ever Made. New York: Warner Books. 1996. p. 49.

- ↑ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

- ↑ Film Curator, (NCMA), the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, North Carolina "Gould and Sutherland had rebelled on the set, convinced that Altman's unstructured directing would destroy their fledgling careers."

- ↑ metro Entertainment, August 4, 2014 Archived October 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine., "Elliott Gould talks Robert Altman and says he never tried to get him fired"

- ↑ Film Curator, (NCMA), the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, North Carolina. "Between 1957 and 1964 he worked on at least 20 TV shows... fired from most of them for his experimentation with non-linear narrative and overlapping sound."

- ↑ Film Curator, (NCMA), the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, North Carolina, quote attributed to Robert Altman

- ↑ Robert Altman (director commentary) (2002-01-08). M*A*S*H (DVD). Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment.

- ↑ "Enlisted: The Story of M*A*S*H" (making-of documentary), Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2001.

- ↑ Robert Altman (director commentary) (January 8, 2002). M*A*S*H (DVD). Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment.

- ↑ Film Curator, (NCMA), the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, North Carolina. "There was absolutely no mention of Korea in the movie, and Fox insisted that be fixed. An introductory title and the PA announcements were used..."

- ↑ Film Curator, (NCMA), the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, North Carolina. "An introductory title and the PA announcements were used to clarify that this was certainly -not- the current Asian war, Vietnam."

- ↑ M*A*S*H Collector's Edition, "Director's Commentary" track. ASIN No. B000BZISTE. Released February 7, 2006.

- ↑ Vatnsdal, Caelum (January 10, 2012). "John Schuck". The A.V. Club. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ https://movies.stackexchange.com/questions/16532/what-is-the-first-appearance-of-the-f-bomb-in-a-movie. Retrieved November 6, 1967.

- ↑ "1970 Box Office in France". Box Office Story.

- ↑ "M*A*S*H (1970)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ "MASH Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: MASH". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "Big Rental Films of 1973", Variety, January 9, 1974 p. 19.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: MASH (film) |

- MASH on IMDb

- MASH at the TCM Movie Database

- MASH at AllMovie

- MASH at Rotten Tomatoes

- MASH at Box Office Mojo

- Elliott Gould remembers M*A*S*H, from the BBC website; in RealMedia