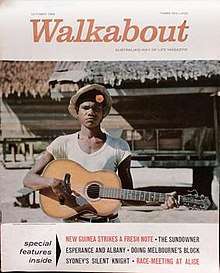

Walkabout (magazine)

Walkabout was an Australian illustrated magazine published from 1934 to 1974 combining cultural, geographic, and scientific content with travel literature.[1] Initially a travel magazine, in its forty-year run it featured a popular[2] mix of articles by travellers, officials, residents, journalists, naturalists, anthropologists and novelists, illustrated by Australian photojournalists. Its title derived from the supposed ‘racial characteristic of the Australian aboriginal who is always on the move".

History

Ostensibly and initially a travel and geographic magazine published by the Australian National Travel Association (formed in 1929),[3] Walkabout : Australia and the South Seas was named by ANTA director Charles Holmes. In its first issue of 1 Nov 1934,[4] the editorial, signed by Charles (Chas) Lloyd Jones, chair of the board of David Jones and acting chairman of the Australian National Travel Association (ANTA), proclaimed its aim to educate its readers;

[I]n publishing ‘Walkabout’, we have embarked on an educational crusade which will enable Australians and the people of other lands to learn more of the romantic Australia that exists beyond the cities and the enchanted South Sea Islands and New Zealand[5]

The income the Association derived from magazine sales provided for its other activities in promoting tourism, 'to place Australia on the world's travel map and keep it there.'[6] It was assertively Australian[7] in its ethos but took cues from other popular magazines of the period, such as the United States' National Geographic Magazine, and LIFE.

From August 1946, Walkabout also doubled as the official journal of the newly formed Australian Geographical Society (AGS), founded with a ₤5,000 grant from ANTA, its banner subscript reading 'Journal of the Australian Geographical Society'. This role is now filled by Australian Geographic magazine. Later it became ‘Australia's Way of Life Magazine’ when supported by the Australian National Publicity Association and later the Australian Tourist Commission.

Editorship

Charles Holmes was Walkabout’s founding managing editor, retiring in August 1957. From June 1936 he was paid £250 p.a. and C. S. Weetman was appointed associate editor at £100, with their allowances coming from the magazine's income and being conditional on its profitability. Basil Atkinson was editor until January 1960; then Graham Tucker followed by film critic and photojournalist Brian McArdle (1920-1968) from January 1961. In the following financial year subscribers to Walkabout came from 91 different countries. Under a new banner 'Australia's Way of Life Magazine' (after November 1961), modern dynamic layouts in a larger format (27 x 33 cm) and more lively captioning saw a brief peak in circulation to 50,000 in 1967 in response to more liberal human-interest and cultural content. McArdle consciously emulated the American Life magazine (1936-1972) and the French Réalités (1946-1979). In the 1960s the magazine spawned a number of book-length illustrated anthologies.[8][9][10][11] After McArdle's illness and death, John Ross took on the editorship in December 1969 with various others filling the role, and the magazine format was reduced to 20 x 27.5 cm until it ceased publication in 1974.

Contributors

Writers included some of Australia's most significant authors, novelists, journalists and commentators:

- Patsy Adam-Smith

- Robin Boyd

- Wilfred Burchett

- Frank Clune

- Eleanor Dark

- Frank Dalby Davison

- James Devaney

- Henrietta Drake-Brockman

- Keith Dunstan

- Elizabeth Durack

- Mary Durack

- Flora Eldershaw

- J. K. Ewers

- George Farwell

- Dorothy Green

- Bill Harney

- Enid Moodie Heddle

- Brett Hilder

- Ernestine Hill

- Ion Idriess

- Rex Ingamells

- Stan Marks

- Alan Marshall

- Hugh McCrae

- Walter Murdoch

- Vance Palmer

- James Pollard

- Leslie Rees

- Colin Roderick

- Kenneth Slessor

- Kylie Tennant

- Arthur Upfield

- Judith Wright

Western Australian writer Henrietta Drake-Brockman originated the ‘Our Authors’ Page’,[12] a full-page feature on a leading writer, which was given a leading position in each issue opposite the table of contents between 1950 and 1953.[7]

A book review column ran almost continuously from 1953—1971 under the byline ‘Scrutarius’ (who was journalist H. C. (Peter) Fenton), totalling almost 200 columns and which reviewed usually four books per issue. The magazine thus provided a showcase of diverse Australian literature to a mostly 'middlebrow' audience that was otherwise ill-served by other periodicals and newspapers.[7]

Photojournalism

ANTA recognised that the magazine it intended to publish would only be successful if it were well illustrated. Its 16th board meeting, held in Sydney in May 1934, passed a motion to employ a staff photographer for the purposes of improving "the quality of 'arresting pictures' that were being forwarded to overseas papers and magazines". Roy Dunstan, a Victorian Railways employee who was possibly known to the first editor Holmes, since both worked for the railways,[7] was appointed on a salary of £9 per week with all expenses paid, increased to £10 per week from 1 September 1938.[13]

Walkabout became an outlet for, and promoter of, Australian photojournalism. Stories were liberally illustrated each with up to fifteen quarter-, half- and full-page photographs in black and white, and from the 1960s, sepia and colour photographs. (Walkabout also sponsored a national artistic and aesthetic photography competition in 1957 with a One Hundred Pound first prize). The original photography segment was later called "Our Cameraman's Walkabout", "Australia and the South Pacific in Pictures" (briefly including New Zealand in the title), "Australia in Pictures", "Camera Supplement" and after 1961, "Australian Scene". It began with as many as 23 photographs spread over 6-8 pages, but dropped to 6-10 photographs in the 1960s. The segment was often devoted to a single topic and in the 1960s to single-topic double-page spreads.

Significant Australian photographers included in its pages were;

- David Beal,

- Jeff Carter and Mare Carter,

- Harold Cazneaux,

- Alan Chapple,

- Beverley Clifford,

- Rennie Ellis,

- Max Dupain,

- Leo Duykers,

- Lee Geoffrey,

- Heather George,

- Helmut Gritscher,

- Frank Hurley,

- Laurence Le Guay,

- Brian McArdle,

- Robert McFarlane,

- Ern McQuillan,

- Harry Mercer,

- David Moore,

- Lance Nelson,

- Russell Roberts,

- Wolfgang Sievers,

- Mark Strizic,

- John Tanner,

- Jozef Vissel

- Richard Woldendorp

Photographs from Walkabout are indexed online at the National Library of Australia

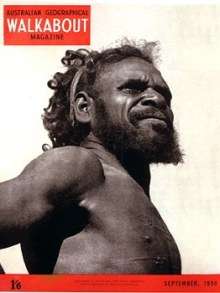

Representation of indigenous Australians

The cover of the first issue of Walkabout featured a silhouette of an Aboriginal man taken (on Palm Island) by German-born British photographer Emil Otto Hoppé (1878–1972) who in 1930 was commissioned to document Australia’s ‘true spirit’ and toured extensively throughout the country, including Tasmania.[14] Otherwise, the first edition includes no articles specifically on Aborigines but in accounting for the magazine’s name, it connected the magazine with an Aboriginal heritage:

The title has an ‘age-old’ background and signifies a racial characteristic of the Australian aboriginal who is always on the move. And so, month by month, through the medium of pen and picture, this journal will take you on a great ‘walkabout’ through a new and fascinating world below the Equator.[15]

Walkabout's early to mid-century stance on depiction of Indigenous Australians was generally conservative, patronising, romantic, often racist and stereotyped,[16] though mixed with some informed commentary and genuine concern (misguided and otherwise),[7] in a reflection of the then prevailing national attitudes.[17] Most issues were inclusive of Aborigines in photo spreads, more typically of Aborigines in so-called traditional poses or settings.

An instance (see: "The Language of Tourism") was Roy Dunstan's full-length portrait entitled "Jimmy" of 1935, standing heroically with a spear and gazing to the distance. 'Jimmy' was Gwoya Jungarai, a Walbiri man, but when his image, cropped to head and shoulders,[18] appeared on the 1950 Australian stamp it was captioned just 'Aborigine'. Though belatedly named in an editorial essay, the deprecating moniker 'One Pound Jimmy' stuck.[19]

However stereotyped or cursory such inclusions might have been,[20] they did promote an understanding of an enduring and significant Aboriginal presence, and of a rich cultural heritage.[21] Specialist essays, written for a general audience, covered topics including: Aboriginal art; black trackers; the peoples of the Torres Strait Islands and Groote Eylandt; missions; Aboriginal bird and place names; Aboriginal weapons and tools; poetry and ritual; the skills and division of labour in fishing, hunting and gathering activities; foodstuffs; Aboriginal pastoral workers; and sea craft.[7]

Ion Idriess, Mary Durack and Ernestine Hill in their frequent writings for the magazine present complex and ambivalent attitudes to the indigenous. Despite their familiarity with Aborigines, they saw them as ‘vanishing’[22] due to unexplained causes and agencies of which even Aborigines themselves were ignorant, and an insufficient birth rate to sustain their population, explained as an instinctual ‘racial suicide’.

Conversely, regular contributor Bill Harney, cattleman, former patrol officer and protector of Aborigines and father of Wardaman elder Bill Yidumduma Harney, penned sixteen articles over 1947–57 presenting an experienced and sympathetic view of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia’s Northern Territory alongside whom he worked and lived.

Anthropologists Ronald Berndt[23] and Frederick McCarthy[24][25][26][27] contributed learned articles, mostly on cultural artefacts. Ursula McConnel's three articles, all in successive issues during 1936 and drawn from fieldwork she had undertaken in Cape York from 1927 to 1934, provided particular insights into the impact on Aborigines experiencing the transition from traditional practices to mission life,[28] frankly identifying ideological failures of policy by the missions' and government administrations and advancing several remedies to the damage she saw being caused to Aboriginal lives and cultures by 'civilisation'.[7] Early articles by anthropologist Donald Thomson were based on his fieldwork in Cape York, northeast Arnhem Land and the Great Sandy Desert,[29] and from 1949 he also contributed a series of ‘Nature Diaries’ on Australian flora and fauna, but he also expressed passionate advocacy for Aborigines out of his frustration with how Aborigines were treated and general contempt for them as little but savages, and his sympathy and deep respect for them and their cultures,[7] writing that he ‘felt that [he] had more in common with these splendid and virile natives than with my own people’.[30]

The magazine reviewed more enlightened literature as early as 1952, including poet Roland Robinson’s studies of traditional Aboriginal knowledge Legend and Dreaming as related to Roland Robinson by Men of the Djauan, Rimberunga, Mungarai-Ngalarkan and Yungmun Tribes of Arnhem Land (1952, with a foreword by A. P. Elkin)[31] and children’s literature dealing with indigenous subjects, such as Rex Ingamells’s Aranda Boy (1952),[32] the latter being praised for its readability and its politics in showing "that the Australian aboriginal is not merely a 'native'.”. In the column 'Our Authors' James Devaney’s popular historical novel The Vanished Tribes (1929), is described as ‘the first really successful treatment in creative prose of our Aboriginal theme, but it is as vitally human and beautifully written a book as we possess’.[33]

By the sixties outrage in the Australian community at the injustice of apartheid in South Africa and consciousness of other social movements for civil rights changed attitudes[34] to the indigenous population and eased the passing of the 1967 Referendum which was to override prejudicial state laws and open the way to advances in land rights,[35][36] discriminatory practices,[37] financial assistance,[38][39] and preservation of cultural heritage.[40] Despite the complexities of the Referendum, it received scant, and belated, mention in Walkabout in 1967.[7] However, articles from this period more even-handedly acknowledged the colonial massacres [41] alongside more sympathetic, though still somewhat patronising, stories on the remote desert tribes,[42] and more in-depth and academic discussion of the complex issues of alcohol and indigenous employment appeared,[43] though much ink was devoted to debate over whether 'aborigine', 'Aborigine, or 'aboriginal' were correct English usage.[44][45][46][47]

Writing about Walkabout's treatment of Australian indigenous people in their 2016 text,[7] Mitchell Rolls and Anna Johnston conclude;

...it is in the manifest tensions between and within the various articles discussing Aborigines and their affairs, and those overtly critical of Aboriginal policy, that Walkabout’s contribution to Aboriginal representation and issues is best found. It is here where one finds the grist for a better and more empathic understanding of these contested and complex issues. In this way[...] Walkabout was doing ‘something immensely valuable’.

Cessation

In the 1970s, despite claiming to be 'The New Walkabout',[48] the magazine was floundering, frequently changing its subtitle and editorship and in 1971 ANTA substantially increased its cover price from 40 cents to 50 cents a copy (a rise from $4.29 to $5.36 in 2017 values), but failed to turn a profit. In accounting for its demise, University of Queensland's Dr. Max Quanchi writes '...it finally struggled against mass circulation weekly and lifestyle magazines in the early 1970s...'. In fact, Walkabout outlived LIFE by two years, with both magazines, amongst many others, succumbing to increasing publication costs, decreasing subscriptions, and to competition from other media and newspaper supplements.

Bibliography

- Bolton, A. T. (ed.) WALKABOUT'S Australia : an anthology of articles and photographs from Walkabout magazine. Sydney: Ure Smith, 1964 ISBN T000019430

- McGuire, M. E. (1993), ‘Whiteman's walkabout’, Meanjin, [52:3]:517-525.

- Quanchi, Max (2004) Contrary images; photographing the new Pacific in Walkabout magazine. Journal of Australian Studies (79):73-88

- Rolls, Mitchell (2009): Picture imperfect: re-reading imagery of Aborigines in Walkabout, Journal of Australian Studies, (33:1): 19-35

- Rolls, M. (2010). Reading Walkabout in the 1930s. Australian Studies, 2.

- Rolls, Mitchell & Johnston, Anna, 1972-, (co-author.) (2016). Travelling home, Walkabout magazine and mid-twentieth-century Australia. London, UK New York, NY Anthem Press, an imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

- Russell, Lynette (1994), "Going Walkabout in the 1950's: images of 'traditional' Aboriginal Australia [in Walkabout magazine.]", Bulletin (Olive Pink Society), 6 (1): 4–8, ISSN 1037-0730

References

- ↑ "NEW TRAVEL MAGAZINE." "Walkabout", a new monthly travel magazine, which will present the story of Australia beyond the cities, the South Sea Islands, and New Zealand, is being produced by the Australian National Travel Association, an organisation established five years ago, with the support of Governments and private enterprise, to make Australia's attractions known throughout the world. Containing 68 pages, the various issues of Walkabout will contain colourful articles by well-known writers. Pictures will be a feature of the new publication. In an explanatory note the publishers state:-"The title adopted for the magazine has an 'age-old' background and signifies a racial characteristic of the Australian aboriginal, who is always on the move. And so,month by month, Walkabout will take its readers on a great 'walkabout' through the fascinating world below the equator." "NEW TRAVEL MAGAZINE". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 30 October 1934. p. 6. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ "It was immediately successful, with its initial print run of 20,000 copies increasing to 22,000 within three months, and reaching 30,000 by 1949." Ross, Glen. The fantastic face of the continent: the Australian Geographical Walkabout magazine. Southern Review (Adelaide), v.32, no.1, 1999: 27-41.

- ↑ Hogben, Paul, (editor.); O'Callaghan, Judith, 1954-, (editor.) (2014), Leisure space : the transformation of Sydney, 1945-1970, Sydney NewSouth Publishing, p. 36, ISBN 978-1-74223-382-6

- ↑ Ross, Glen. The fantastic face of the continent: the Australian Geographical Walkabout magazine. Southern Review (Adelaide), v.32, no.1, 1999: 27-41.

- ↑ Editorial, Walkabout, November 1934, 7.

- ↑ http://www.nla.gov.au/exhibitions/sun/anta.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Rolls, Mitchell; Johnston, Anna, 1972-, (co-author.) (2016), Travelling home, Walkabout magazine and mid-twentieth-century Australia, London, UK New York, NY Anthem Press, an imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1-78308-537-8

- ↑ A. T. Bolton, editor (1968) Walkabout's Australia : an anthology of articles and photographs from Walkabout magazine. Sydney : Ure Smith in association with the Australian National Travel Association, – Walkabout pocketbooks

- ↑ Farwell, G., Brian McArdle [ed.] (1968) Around Australia on Highway One. Melbourne, Vic. : Thomas Nelson (Australia)

- ↑ Tennison, P., McArdle, J.B. (196?) Walkabout presents the Australian scene. Melbourne: Walkabout.

- ↑ McArdle, B. & Fenton, P. (1968) Australian Walkabout. Melbourne : Lansdowne Press.

- ↑ Editor, ‘Acknowledgment’, Walkabout, August 1950, 37.

- ↑ ANTA Board Minutes, Sydney, 8 August 1939; ANTA Board Minutes, Canberra, 11 October 1938

- ↑ Hoppé, E. O. (Emil Otto) (1931), The fifth continent, Simpkin Marshall

- ↑ e.g. Walkabout, November 1934, 9.

- ↑ Russell, Lynette (1994), "Going Walkabout in the 1950's: images of 'traditional' Aboriginal Australia [in Walkabout magazine.]", Bulletin (Olive Pink Society), 6 (1): 4–8, ISSN 1037-0730

- ↑ For a full discussion see: Rolls, Mitchell (2009): Picture imperfect: re-reading imagery of Aborigines in Walkabout, Journal of Australian Studies, (33:1): 19-35

- ↑ The cropped print, marked as originating from the files of the ANTA, publisher of Walkabout, is held by the National Library of Australia. In the online catalogue, annotations on the back of the print are transcribed; : "Australian aborigines in some of the remote areas of the Interior still live after the fashion of the Stone Age. They hunt their food with spear, stone axe and wear no clothes of any description."; typescript on the reverse, ca. 1941

- ↑ See: McGuire, M.E. "Whiteman's Walkabout" [online]. Meanjin, Vol. 52, No. 3, Spring 1993: 517-525

- ↑ Lynette Russell, ‘Going Walkabout in the 1950’s: Images of “Traditional” Aboriginal Australia’, The Olive Pink Society Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1994): 4–8

- ↑ Mitchell Rolls, ‘Picture Imperfect: Re-reading Imagery of Aborigines in Walkabout’, Journal of Australian Studies 33, no. 1 (2009): 19–35.

- ↑ Mary Durack, ‘The Vanishing Australian’, Walkabout, August 1945, 31.

- ↑ R. M. Berndt, ‘Aborigines of the Great Western Desert’, Walkabout, December 1940,40–42.

- ↑ F. D. McCarthy, ‘Utensils of the Australian Aborigine’, Walkabout, August 1957,36–37.

- ↑ F. D. McCarthy, ‘Australian Aboriginal Basket-Makers’, Walkabout, September 1957, 36–37.

- ↑ F. D. McCarthy, ‘Island Art Galleries’, Walkabout, February 1964, 38–40.

- ↑ F. D. McCarthy, ‘The Rock Engravings of Depuch Island, North-West Australia’, Records of the Australian Museum 25 (1961): 121–48.

- ↑ Ursula H. McConnel, ‘Cape York Peninsula: (1) the Civilised Foreground’, Walkabout, June 1936, 16–19; Ursula H. McConnel, ‘Cape York Peninsula: The Primitive Playgound’, Walkabout, July 1936, 10–15; Ursula H. McConnel, ‘Cape York Peninsula: Development and Control’, Walkabout, August 1936, 36–40

- ↑ Donald F. Thomson, ‘Across Cape York Peninsula with a Pack Team: A Thousand- Mile Trek in Search of Unknown Native Tribes’, Walkabout, December 1934, 21–31

- ↑ Donald F. Thomson, ‘The Story of Arnhem Land’, Walkabout, August 1946, 4–22

- ↑ Robinson, Roland (1952), Legend & dreaming : legends of the dream-time of the Australian Aborigines as related to Roland Robinson by men of the Djauan, Rimberunga, Mungarai-Ngalarkan and Yungmun tribes of Arnhem Land, Edwards & Shaw

- ↑ Ingamells, Rex; Leong Pak Hong, (illustrator.) (1952), Aranda boy : an aboriginal story, Longmans Green

- ↑ Rex Ingamells, ‘Our Authors’ Page: James Devaney’, Walkabout, February 1952, 8–9.

- ↑ "Many changes in Aborigines' rights and treatment followed, including at long last full voting rights. The government gave the Commonwealth vote to all Aborigines in 1962. Western Australia gave them State votes in the same year. Queensland followed in 1965. With that, all Aborigines had full and equal rights. In 1971 the Liberal Party nominated Neville Bonner to fill a vacant seat in the Senate. He was the first Aborigine to sit in any Australian Parliament."Australian Electoral Commission "Indigenous Australians and the vote" retrieved 15 Feb 2013

- ↑ Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth).

- ↑ Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

- ↑ Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth).

- ↑ States Grants (Aboriginal Advancement) Act 1972 (Cth).

- ↑ Aboriginal Loans Commission Act 1974 (Cth).

- ↑ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage (Interim Protection) Act 1984 (Cth).

- ↑ Murphy, J.E. 'The Massacre at Cullin-La-Ringo' Walkabout June 1966, p.20-21

- ↑ Rose, R. 'Man of the Desert' Walkabout, July 1966, p.20-21

- ↑ Graham, D. The 'Aborigine and the Future' Walkabout January 1968, p. 32-34

- ↑ J. W. Davidson, ‘Aborigine and Aboriginal’, Walkabout, July 1964, 5.

- ↑ S. A. Luck, ‘We Stick to Aborigine’, Walkabout, January 1965, 6.

- ↑ A. H. Chisholm, ‘Aborigine or Aboriginal’, Walkabout, April 1965, 6–7.

- ↑ J. D. Jago, ‘Capital Aborigines’, Walkabout, July 1968, 7.

- ↑ Editorial, Walkabout, August 1971, 5.