Steamboats on the Volga River

The Volga River is Europe's longest river, and a major trade artery in that continent. The technological arrival of the steam engine allowed cargoes to be more easily moved upstream. The use of steamboats on the Volga River began in the year 1821.

History

Volga boatmen

_-_Volga_Boatmen_(1870-1873).jpg)

Formerly, tens of thousands of burlaki, or Volga boatmen, were employed in dragging boats up the Volga and its tributaries, but this method of traction has disappeared.[1] Horses were still extensively used along the three canal systems. Steamers really took hold in the 1840s.

First steamers

In 1843 Czar Nicholas I issued a license to the "Along the Volga" Company in 1843, which became the premier Volga Flotilla until the Soviet takeover. The first steamer "Volga" visited Samara in 1846.[2] Nizhniy is the chief station of the Volga steamboat traffic. The first steamer made its appearance on the Volga in 1821, but it was not till 1845 that steam navigation began to assume large proportions.

The first large steamers of the American type were built in 1872.[1]

Thousands of steamers are now employed in the traffic, to say nothing of smaller boats and rafts. Many of the steamers use as fuel mazut or petroleum refuse.[1] In 1870, the first Russian open hearth furnace was built in Nizhny Novgorod, followed by a two-decked steamship "Perevorot" just a year later. In 1913, it produced a dry bulk cargo ship "Danilikha". The shipyard built 489 ships between 1849 and 1918.

In 1913 there were over 5,000 steamers on the Volga river system.

Engines for Commerce

Batashev's steamers were on par with the world-famous engines produced by Berdov, and were installed on the majority of Volga steamships. Berdov's plant in St. Petersburg was the first to build a steamboat in Russia in 1815. It later specialised in stationery and marine machines, as well as marine devices. Building small warships from the 1850s, the plant rented the shipyard on Galerny Island for a ten-year period to start building battleships. Numerous decorative sculptures were created in the foundry shop in the early to mid 19th century including sculptures for the Kazan Cathedral, St. Isaac's Cathedral, and the Alexander Column, as well as numerous grilles, lamps, decorative and structural components for bridges, palaces, and public buildings of St. Petersburg.

Many cargoes

The Volga is the main street of European Russia. To this end many loads are moved from their source to the market—coal from the Donbass Region, iron ore, minerals, timber, wheat, fish, watermelons, zeks or exiles, machinery, cement, limestone, and oil.

Various troubles

In 1897 the New York Times reported "FORTY DROWNED IN THE VOLGA.; Steamer Tsarevitch Run Down by the Malpitka Near Astrakhan."[3] In 1858, the Nizhny Novgorod Machine Factory produced the first Russian steam dredger. The amount of suspended matter brought down by erosion is correspondingly great. All along its course the Volga is eroding and destroying its banks with great rapidity; towns and loading ports have constantly to be shifted farther back.[1]

Alfred Nobel built fifty steamers at Baku to move Caspian oil. He also built the MS Vandal, which in 1903, was probably the first ship (and not barge) propelled by a diesel engine.[4][5] In 1902 Karl Hagelin, "a veteran of the Volga and sometime visionary",[6] suggesting mating diesel engines to river barges. He envisioned direct shipment of oil through a 1,800-mile route from the lower Volga to Saint Petersburg and Finland.[6] The first Volga steamers 'Komar', 'Shmel', and 'Tungus' were constructed between 1908 and 1917 in the Nobel Shipyard in Rybinsk.[7]

The Russians move large amounts of timber for export to Europe. Large barges of 300 ft (91 m) length to 1,000 t (1,102 tons) are purpose built for the single journey in the season. Large numbers of the boats and rafts are broken up after a single voyage.[1] The wood barges are towed by tug.

Soviet era

The Soviets ran fleets of armed riverboats during the Civil War. The Red Army and the White Army had small naval battles on the river. Later, during the Russian famine of 1921, steamers became a way out of misery.[8] With the Red control of Russia, rebuilding infrastructure became paramount.[8] The Soviets nationalized the Volga and Mercury company's fleets.

The largest fleet of any of Soviet rivers is that on the Volga, where in 1926 there were 1,604 steamers with an indicated total horse power of 300,595. On January 1, 1927, the Internal Waterways Steamship Co. had at its disposal 2,020 steamers.[9] (Presumably the Russian Civil War accounts for the destruction of more than half the fleet)

World War II and beyond

At the start of the Battle of Stalingrad, and before the Wehrmacht reached the city itself, the Luftwaffe had rendered the River Volga, vital for bringing supplies into the city, unusable to Soviet shipping.[10] Between 25 and 31 July 1942, 32 Soviet ships were sunk, with another nine crippled.

However, the Soviets put up a valiant defense. During the Battle of Stalingrad, one indomitable tug "Krasnoflotets" crossed the river towing barges of men, food and ammunition, constantly under the fire of the German guns. The tug made many journeys until it was too damaged to continue. One hospital ship was struck by German artillery 11 times.

The Stalingrad epic for "Gasitel" began on July 27, 1942, when the enemy set fire to the oil tankers near Erzovka. The courageous crew risking their lives saved the oil tankers and took the barges with oil to Shadrinsk backwater. In the midst of the battle of Stalingrad, "Gasitel" was used at river crossings. The vessel had received numerous holes, the team repaired them on their own, without going into the backwater. The crew had to constantly pump out the water that came through the holes in the ship . These were all the fiery days of navigation in 1942. For his bravery the steamer captain Peter Vasilievich Vorobiev was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. In mid-October riddled with bullets "Gasitel" had sunk. One river paddler removing women and children refugees from the city was shelled and sunk. Three thousand people drowned.

The Soviets doggedly held the ferry building on September 14 with one hundred soldiers and a semi-operable tank. More soldiers were rushed in by steamer to the key river landing.

The German armies later overran the ferry landing, while the Soviets stubbornly held on to a sliver of the western riverbank of the Volga. The tug Abkhazets and others moved 7 Soviet divisions across the river to Crossing 62 to provide General Chuikov with new troops.

The Soviet navy built armed cutters, sporting T34 tank turrets. This "Volga Flotilla made the Red Army's greatest victory possible, keeping open supply lines to the troops fighting for their lives in the ruins of Stalingrad. Gunboats armed with 76 mm (3 in) anti-aircraft guns fought off German Stuka attacks throughout the siege, and those with tank turrets hove close to the riverbanks to provide fire support for the troops ashore. Every night, they ferried reinforcements and ammunition across the river, and brought back the wounded to safety.[11][12]

"About the role of the sailors of the fleet and their exploits", wrote Vasily Chuikov, the Soviet commander in Stalingrad, "I would say briefly that had it not been for them the 62nd Army might have perished without ammunition and rations, and could not have carried out its task."[11][12] The Germans surrendered in the winter of 1943 and the Volga was once again open to steamers after the removal of war wreckage.

During the Great Patriotic War, river transport carried approximately 200 million tons of cargo for the front and the rear. River workers worked at the military crossings at Stalingrad and on Lake Ladoga. The war caused enormous damage to river transport. The fascist occupying troops sank and seized more than 8,300 river vessels and destroyed hundreds of ports, wharves, dams, dikes, and locks. River transport was rebuilt during the Fourth Five-Year Plan (1946–50).

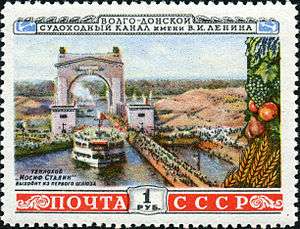

The Soviets embarked on a huge series of dams, canals, barrages, lakes and hydro schemes. Much of this had been planned prior to the war but that tragedy only delayed their completion. Control of river erosion, and silting was one reason; providing enough draft for large ships and clearing rapids was another. The Volga-Don Canal was one scheme, and the Volga-Baltic Waterway another.

Most of the keels on the river were of the paddle steamer type. Up until 1950, the Soviets continued with this layout.

With the new hydrological and hydroelectric work, new ships needed to be built. In the post-war years, new steamers of the Josef Stalin type were built and navigated the river.

The Soviets then went into hydrofoils and diesel steamers A few steamers have survived. Today, the river is worked by diesel cruise boats and tugs.

Notable events

In 1913, the Romanovs boarded the steamer "Mezhen" at Nizhny Novgorod to sail down the Volga river for their 500th Anniversary tour.

Maxim Gorky, the writer, worked as a cook on a Volga steamer in his youth and thus the Volga river enters Russian literature: stories where a young officer encounters a beautiful stranger on board a Volga steamer.

In Russian life, the Volga is like the sky and air. We breathe the Volga, we are enrapt with her. We sing the most heartfelt songs about her. We teach our children her traditions and legends.

Konstantine Fedin, wrote to his American allies, comparing the Volga to the Mississippi, and reminding them of the rampaging German Army then in conquest in the dark days of 1942.

"The Volga is the homeland of daring, courage, and the people's glory. The Volga is the homeland of Russian geniuses and talents.

From childhood, people on the Volga dream about their river as the most beautiful of all earthly gifts which have been bestowed upon them. When I was a child sitting at my school bench, I imagined Volga steamers, rafts, and boats sailing past, like a holiday; green islands stretched out before me; the silver of fish scales sparkled; I breathed the aroma of the swaying shoreline willows. All this was living right next to me. I knew that after lessons I could run along the Volga and touch all this with my own hand."

See also

References

- Sources

- Bartlett, George H., “To Samara from Moscow, via Nizhni and the River Volga”, The Harvester world, Volumes 2-3, (published by International Harvester Co.) (1910), at page 22. (accessed 07-04-11). (describes a trip by steamboat by a salesman for International Harvester Co. on the Volga river in 1910.)

- Ellis, William T., “Voyaging on the Volga Amid War and Revolution”, National Geographic Magazine, Volume 33 (1918), page 245. (accessed 07-04-11)

- Gardiner, Robert; Greenway, Ambrose (1994). The golden age of shipping: the classic merchant ship, 1900–1960. Conway Maritime. ISBN 0-85177-567-5.

- Graebner, Walter, “1000 Miles up the Volga, Life magazine, September 7, 1942, at page 2 (accessed 07-04-11) (describes journey on Volga River during World War II).

- The Beginning of the Road: The Story of the Battle for Stalingrad, London, 1963.[13]

- Thomas, Donald E. (2004). Diesel: Technology And Society In Industrial Germany. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5170-1.

- Tolf, Robert (1976). The Russian Rockefellers: the saga of the Nobel family and the Russian oil industry. Hoover Press. ISBN 0-8179-6581-5.

- United States Dept. of Commerce, Special Consular Reports, Vol 13, Issue 1, page 394 (accessed 07-04-11) (summarizes steamboat, routes, and fares on the Volga River and tributaries as of 1895)

- CIA. Soviet Shipping. Washington. 1950.

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5

- ↑ Samara Tourist Guide (2011). "Samara Travel Guide". myeuropeholidays.com. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

The first steamer 'Volga' visited to Samara in 1846.

- ↑ "FORTY DROWNED IN THE VOLGA. - Steamer Tsarevitch Run Down by the Malpitka Near Astrakhan. - View Article - NYTimes.com" (PDF). The New York Times. 17 September 1897. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ↑ sources disagree over whether, Vandal or Petite-Pierre, was the first diesel ship: Thomas, p. 207: Petite-Pierre was the first diesel ship. Gardiner and Greenway, p. 160: Vandal was the first diesel ship.

- 1 2 Tolf, p. 171.

- ↑ Nobel Shipyard (2011). "About Company | Nobel Shipyard". nobel-shipyard.ru. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- 1 2 Patenaude, Bertrand M. (2011). "Food as a Weapon | Hoover Institution". hoover.org. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Marxists.Org (2009). "The Soviet Union: Facts, Descriptions, Statistics — Ch 8". marxists.org. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ↑

"Battle of Stalingrad". Encyclopædia Britannica.

By the end of August, … Gen. Friedrich Paulus, with 330,000 of the German army's finest troops… approached Stalingrad. On August 23 a German spearhead penetrated the city's northern suburbs, and the Luftwaffe rained incendiary bombs that destroyed most of the city's wooden housing.

- 1 2 Avalanche Press (2011). "119694_avalanche Press". avalanchepress.com. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

I would say briefly that had it not been for them the 62nd Army might have perished without ammunition and rations, and could not have carried out its task.

- ↑ Keegan, John. The Battle for History: Re-fighting World War Two (Barbara Frum lecture series), Vintage Canada, Toronto, 1995. Republished by Vintage Books, New York, 1996.:121

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steamboats on the Volga River. |