Volcán de Fuego

| Volcán de Fuego | |

|---|---|

Volcán de Fuego, 1974 eruption. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,763 m (12,346 ft) |

| Coordinates | 14°28′29″N 90°52′51″W / 14.47472°N 90.88083°WCoordinates: 14°28′29″N 90°52′51″W / 14.47472°N 90.88083°W |

| Geography | |

Volcán de Fuego | |

| Parent range | Sierra Madre |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 200 Kyr |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano (active) |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Central America Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 2002 to 2018 (ongoing)[1] |

Volcán de Fuego (Spanish for "Volcano of Fire", often shortened to Fuego) or Chi'gag (Mayan for "where the fire is") is an active stratovolcano in Guatemala, on the borders of Chimaltenango, Escuintla and Sacatepéquez departments. It sits about 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) west of Antigua, one of Guatemala's most famous cities and a tourist destination.[2] It has erupted frequently since the Spanish conquest, most recently in June 2018.[3][4][5]

Fuego is famous for being almost constantly active at a low level. Small gas and ash eruptions occur every 15 to 20 minutes, but larger eruptions are rare. Andesite and basalt lava types dominate, and recent eruptions have tended to be more mafic than older ones.[6]

The volcano is joined with Acatenango and collectively the complex is known as La Horqueta.

Early expeditions

In 1881, French writer Eugenio Dussaussay climbed the volcano, then practically unexplored.[7] First, he needed to ask for permission to climb from the Sacatepéquez governor, who gave him a letter for the Alotenango mayor asking for his assistance with guides to help the explorer and his companion, Tadeo Trabanino.[8] They wanted to climb the central peak, unexplored at the time, but could not find a guide and had to climb to the active cone, which had a recent eruption in 1880.[9]

British archeologist Alfred Percival Maudslay climbed the volcano on 7 January 1892. Here is how he described his expedition:[10]

[...] we arranged to start the very next day for the village of Alotenango. On the 7th January we left that village about 7 o'clock in the morning with seven Mozos, carrying food, clothing, and my camp-bed, and rode for an hour towards the mountains, when we dismounted and sent back our mules. The first two hours' climb was not so very steep, but it was tiring work walking over the loose mould and dry leaves under the thick forest. [...] we recommenced our climb under shadow of the forest by a steep path cut through the undergrowth. At the height of about 9500 feet we, for the first time since starting, got a sight of the peak rising on the other side of a deep ravine. The whole of the slope on which we looked was bare of vegetation, and presented to the eye nothing but desolate slopes of ashes and scoriae broken higher up with patches of burnt rock; we scrambled on through the thick undergrowth, often with loose earth under foot, and by degrees the vegetation changed and we got amongst the pine-trees. At about 11,200 feet we came to a spot where the earth had been levelled for a few yards by the Indians, and there we determined to pass the night. [...] then returned and watched the reflection of the sunset over the more distant peaks and against the perfect cone of Agua. [...] but the cold which followed the sunset soon took all our attention. [...] We turned out of our shelter at about half-past four in the morning, and felt all the better after drinking hot coffee ; we then sat for an hour watching a most beautiful dawn and sunrise. At the opposite side of the valley rose the Volcano of Agua, sloping on one side to the plain of Antigua, and on the other in a long unbroken sweep to the sea, more than forty miles away. Peak after peak stood out against the red light into the far distance, and on the right the low coast-line and the sea showed up very clearly. As soon as the sun was up we started for the summit. I stopped on the way to get a photograph of the cone, which lay to the left of us as we ascended ; but the clouds came over just as I was ready, and I had to give it up. A little over 12,000 feet we left the scraggy pine-trees and arrived at the northern end of a cinder ridge, called the Meseta, which is at the summit of the slope we had been climbing.

— Alfred Percival Maudslay, A Glimpse at Guatemala

Notable eruptions

| Date | Brief description |

|---|---|

| 1581 | Reported by historian Domingo Juarros. Caused damage in the surrounding area. It is possible the damage was related to earthquakes.[12] |

| 1586 | |

| 1623 | |

| 1705 | |

| 1710 | |

| 27–30 August 1717 | Strong eruption right before the San Miguel earthquake. |

| 1732 | Reported by historian Domingo Juarros. Caused damage in the surrounding area. It is possible the damage was related to earthquakes.[12] |

| 1737 | |

| ca. 1800 | Did not have any catastrophic consequence, although it lasted for several days and heated up a nearby stream to the point that "beasts would not dare to cross it".[12] |

| 1880 | Reported by Eugenio Dussaussay.[13] |

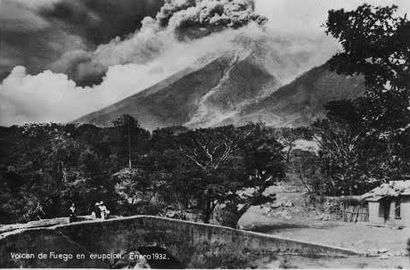

| 1932 | Strong eruption that covered Antigua Guatemala in ash. |

| 15–21 October 1974 | Strong eruption that caused heavy agricultural losses. Pyroclastic flows destroyed all vegetation in the surroundings of the active cone. |

| 1–6 July 2004 | Small eruption preceded by internal explosions. |

| 9 August 2007 | Small eruption of lava, rock and ash. Guatemala's volcanology service reported that seven families were evacuated from their homes near the volcano.[14] |

| 13 September 2012 | The volcano began ejecting lava and ash, prompting officials to begin "a massive evacuation of thousands of people" in five communities.[15] More specifically, the evacuees, roughly 33,000 people, left nearly 17 villages near the volcano.[16] It ejected lava and pyroclastic flows about 600 metres (2,000 ft) down the slope of the volcano.[2] |

| 8 February 2015 | A further eruption resulted in 100 nearby residents being evacuated, and the closure of La Aurora International Airport due to the amount of falling ash.[17] |

| 3 June 2018 | An eruption resulted in at least 159 deaths and at least 300 injuries, 256 missing persons and residents being evacuated, and the closure of La Aurora International Airport.[18][19] |

1717 destruction of Santiago de los Caballeros

The strongest earthquakes experienced by the city of Santiago de los Caballeros before its final move in 1776 were the San Miguel earthquakes in 1717. In the city, people also believed that the proximity of the Volcán de Fuego (English: Volcano of Fire) was the cause of earthquakes; the great architect Diego de Porres even said that all the earthquakes were caused by volcano explosions.[20]

On 27 August there was a strong eruption of Volcán de Fuego, which lasted until 30 August; the residents of the city asked for help to Santo Cristo of the Cathedral and to the Virgen del Socorro who were sworn patrons of the Volcan de Fuego. On 29 August a Virgen del Rosario procession took to the streets after a century without leaving her temple, and there were many more holy processions until 29 September, the day of San Miguel. Early afternoon earthquakes were minor, but at about 7:00 pm there was a strong earthquake that forced residents to leave their homes; tremors and rumblings followed until four o'clock. The neighbors took to the streets and loudly confessed their sins, bracing for the worst.[21]

The San Miguel earthquake damaged the city considerably, to the point that some rooms and walls of the Royal Palace were destroyed. There was also a partial abandonment of the city, food shortages, lack of manpower and extensive damage to the city infrastructure; not to mention numerous dead and injured.[21] These earthquakes made the authorities consider moving to a new city less prone to seismic activity. City residents strongly opposed the move, and even took to the Royal Palace in protest; in the end, the city did not move, but the number of elements in the Army Battalion to safeguard the order was considerable.[22] The damage to the palace was repaired by Diego de Porres, who finished repairs in 1720; although there are indications that there were more jobs done by Porres until 1736.[22]

In 1773, the Santa Marta earthquakes destroyed much of the town, which led to the third change in location for the city.[23] The Spanish Crown ordered, in 1776, the removal of the capital to a safer location, the Valley of the Shrine, where Guatemala City, the modern capital of Guatemala, now stands. This new city did not retain its old name and was christened Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción (New Guatemala of the Assumption), and its patron saint is Our Lady of the Assumption. The badly damaged city of Santiago de los Caballeros was ordered abandoned, although not everyone left, and was thereafter referred to as la Antigua Guatemala (the Old Guatemala).[23]

Eruption of 3 June 2018

Beginning in 2002, the Volcán de Fuego entered a new active period, with more or less continuous activity, interspersed with monthly eruptive episodes. These episodes would typically send ash falling on communities within 20km of the volcano, and lava flows about 1-2km from the summit, and the occasional pyroclastic density current.[24]

On 3 June 2018, the volcano suddenly produced its most powerful eruption since 1974. Large pyroclastic density currents were produced that over-topped the barranca boundaries they had previously been confined to and unexpectedly hit El Rodeo, Las Lajas, San Miguel Los Lotes, and La Reunión villages in Escuintla, which buried the towns and killed many of the surprised residents. Later, 18 bodies were found in the village of San Miguel Los Lotes. Members of the Shriners International fraternity[25] met six of over fifty burned children, ages 1-16[26], that were sent from Guatemala to the Shriners Hospital in Galveston, Texas[27] and accompanied by 5 guardians[25] for receiving the appropriate and medical treatment[26].

Ash fall extended as far as the capital, Guatemala City forcing the closure of La Aurora International Airport. The military assisted in clearing ash off of the runway. Rescue attempts were seriously hampered as routes into the affected regions were seriously damaged by the pyroclastic density currents.[28]. On 5 June[29], Associated Press reported that at least 99 people are dead and nearly 200 others unaccounted for following the eruption[26][29], while some Shriners hospitals were activated for new entries[26].

Gallery

1932 eruption

1932 eruption 2013 eruption

2013 eruption 2011 eruption

2011 eruption 2007

2007 Fuego from Acatenango, 2006

Fuego from Acatenango, 2006- Fuego fumes (left), volcán Acatenango at right, 2009

3D view

3D view

See also

- List of volcanoes in Guatemala

- List of volcanic eruptions by death toll

References

- ↑ "Fuego volcano". 19 February 2018.

- 1 2 "Guatemala's Volcano of Fire erupts, 33,000 evacuated". USA Today. Guatemala City. Associated Press. 13 September 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ "More dangers loom after Guatemala volcano eruption kills over 60 people". CNN. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Gibbens, Sarah (4 June 2018). "Why Guatemala's Volcano Is Deadlier Than Hawaii's". National Geographic. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ Metzen, Ray (4 September 2017). "Unreal Volcanoes Near Antigua Guatemala". Ixchel Spanish School. Antigua Guatemala. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ http://www.geo.mtu.edu/volcanoes/fuego/petro2.html

- ↑ Dussaussay 1897, p. 180.

- ↑ Dussaussay 1897, p. 179-182.

- ↑ Dussassay 1897, p. 179.

- ↑ Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 37-39.

- ↑ Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 Juarros 1818, p. 352

- ↑ Dussaussay 1896, p. 179.

- ↑ "BOLETIN VULCANOLOGICO DIARIO". insivumeh.gob.gt (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ "Eruption at Guatemala volcano forces evacuations". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ↑ "Guatemalan emergency official tells AP more than 33,000 fleeing volcano eruption – 680 NEWS". 680 news. 13 September 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ "Guatemala Volcano Eruption Forces Evacuations". The Guardian. Reuters. 8 February 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ "Guatemala volcano death toll hiked to 159, 256 people still missing". Al Dia Culture. EFE. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ "Guatemala Fuego: Search after deadly volcano eruption".

- ↑ Melchor Toledo 2011, p. 103.

- 1 2 Melchor Toledo 2011, p. 104.

- 1 2 Rodríguez Girón, Flores & Garnica 1995, p. 585.

- 1 2 Foster 2000.

- ↑ Venzke, E, ed. (February 2018). "Report on Fuego (Guatemala)". Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network. 43 (2). Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Shriners Hospitals for Children's response to children burned in Guatemala volcano eruption". June 7, 2018. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved Aug 25, 2018.

Grand Master of Guatemala, Brother Estuardo Ordoñez Kocher, has asked the Masonic Service Association of North America to issue a Disaster Relief Appeal to help his afflicted brethren and their families. He reports that six of over 50 burned children have already been sent to the Shriners Hospital in Galveston, Texas, but, unfortunately, his local resources have been expended.

- 1 2 3 4 M. Rivera (Jun 7, 2018). "ChildrenChildren hurt in Guatemalan eruption receive care at Shriners Hospital in Texas". foxnews.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018.

Shriners provides on-site housing for the families for part of that time. After the patients are sent home, they can be flown from Guatemala back to theU.S. for recurring treatment. Total treatment for each child can reach millions of dollars—at no cost for the patient.

- ↑ "Fuego Folcano Disaster Relief". dcgranlodge.org. Washington D.C. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ "Guatemala volcano: Several dead as Fuego volcano erupts". BBC News. 3 June 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- 1 2 S. Perez (Jun 5, 2018). "Guatemala volcano death toll up to 69, expected to rise". Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved Aug 25, 2018.

Bibliography

- Dussaussay, Eugenio (1897). "Impresiones de viaje: el volcán de Fuego". La Ilustración Guatemalteca (in Spanish). Guatemala: Síguere, Guirola & Cía. I (12).

- Foster, Lynn V. (2000). A Brief History of Central America. New York: Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-3962-3.

- Juarros, Domingo (1818). Compendio de la historia de la Ciudad de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Ignacio Beteta.

- Maudslay, Alfred Percival; Maudslay, Anne Cary (1899). A glimpse at Guatemala, and some notes on the ancient monuments of Central America (PDF). London, UK: John Murray.

External links

![]()