Villa Boscoreale

Villa Regina, view from above. | |

| Location | Boscoreale, Province of Naples, Campania, Italy |

|---|---|

| Region | Magna Graecia |

| Coordinates | 40°45′41″N 14°28′17″E / 40.761389°N 14.471389°ECoordinates: 40°45′41″N 14°28′17″E / 40.761389°N 14.471389°E |

| Type | Dwelling |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Pompei, Ercolano e Stabia |

| Website | Sito Archeologico di Boscoreale (in Italian) |

Many Roman villas have been discovered in the district of Boscoreale[1], Italy. They were all buried and preserved by the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, along with Pompeii and Herculaneum.[2] The only one visible in situ today is the Villa Regina, the others being reburied soon after their discovery. Nevertheless, among the most important finds from these others are the exquisite frescoes from the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor and the sumptuous silver collection of the Villa della Pisanella, which are now displayed in several major museums, as are finds from the Villa del fondo Ippolito Zurlo[3]. The name Villa Boscoreale is typically used for any one of these villas.

In Roman times this area was agricultural, specialising in wine and olive oil.[4]

Other Roman villas that were discovered in the vicinity, often by "treasure" hunters towards the end of the 19th century, and then reburied, include notably those:

- in "d'Acunzo property"

- of N. Popidius Florus, from which frescoes were taken

- in via Casone Grotta (found in 1986)

- of M. Livius Marcellus.

Information on, and objects from, the villas can be seen in the nearby Antiquarium di Boscoreale.

Villa Regina

This rustic villa was discovered more recently in 1977 and therefore has been preserved in its complete state as buried 8m below ground level. The villa is a comfortable working farm rather than a luxurious estate that others nearby were. Nonetheless an elegant central courtyard is colonnaded on three sides with columns of red and white stucco.

Large quantities of pottery and farm implements were found. Plaster casts of the original entrance doors were made from the hollow spaces left. A plaster cast of a pig found here and killed in the catastrophe was also made.

It also includes preserved parts of a wine press.[5] Near the centre of the villa is the wine cellar in which 18 dolia, of total capacity 10,000 litres, were buried for storing the must from the adjoining press.

An unusual find was an oil lamp dating from the 3-5th c. AD showing that the place was tunnelled into in the later Roman era.

The holes in the ground left by the roots of the Roman vines were found and vines have again been planted in them.

Villa of P. Fannius Synistor

Although the villa was of relatively modest size compared to others in the area and had no atrium, pool or sculpture collection, its frescoes were exceptional in their beauty and quality.[6]

Evidence in tablets and graffiti shows that the house was probably built in the 1st century (around 40-30 BC).[7] The villa was privately discovered, excavated, partially dismantled and reburied in 1900.

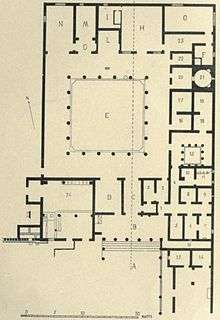

The villa had three stories, complete with a bath suite and an underground passage to a stable and agricultural buildings, the latter not excavated. The central ground floor of the living quarters consisted of over thirty rooms or enclosures surrounding a colonnaded courtyard or peristyle. The building featured an impressive main entrance approached by five broad steps leading to a colonnaded forecourt.

Ownership of the villa has been contested. While there is no doubt P. Fannius Synistor did reside there, excavated bronze tablets show another name, that of Lucius Herennius Florus. Many things were marked with seals in ancient Rome to indicate possession. It is believed that since the tablet with the letters "L. HER. FLO" on the front of it was found inside the villa, it must serve as a mark of villa ownership.[8] These two are the only confirmed owners in the early 1st century BC and 1st century AD, though there may have been earlier owners.

Art

The Villa is most notable for its wonderful works of art, notably its highly skilled buon fresco paintings, said to be the highest quality Roman frescoes ever found[10] and which are now scattered after being auctioned after removal.

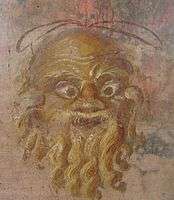

Most of the figures in the frescoes have characteristics of Greek Hellenism or Classicism. For instance, those found in the living room appear to be depictions of either philosophers, such as Epicurus, Zeno or Menedemus, or possibly old kings, like King Kinyras of Cyprus.[11] Similarly, the bedrooms of the Second Style also evoke Hellenistic qualities, such as are seen at the Tomb of Lyson or at Kallikles.[12] At a time when the Roman Republic was ending and classicism somewhat fading, this is considered as an interesting comment on style and taste. Seemingly, Greek representations in the home were considered acceptable, even admired and sophisticated. The images survived the quick succession of Vesuvian cataclysms because of the skill of the fresco work and the absence of organic materials such as indigo, murex purple, red madder among its pigments. The reddening of some of its yellow ochre shows temperatures to have exceeded 300 °C.[13]"

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, together with King's College, London, is building a virtual model of the Villa, linking the scattered frescoes, based on the notes and plan drawn at the time of excavation by archaeologist Felice Barnabei (1902), photographs taken of the excavation, the research of Phyllis W. Lehmann (1953) and axonometric drawings of the plan, locating the images on the walls, by Maxwell Anderson (1987).[14]

Metropolitan Museum cubiculum reconstruction

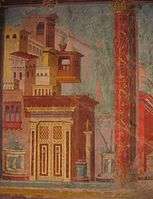

The fullest reconstruction from original frescoes at present is of a bedroom (cubiculum diurnum), one of the holdings of the Metropolitan Museum since 1903, and since 2007 a feature of the new Roman Gallery. It consists of most of a newly cleaned and reconstructed set of walls entirely painted in highly accomplished fresco.[15] These spacious Roman II Style murals represent their walls as open above socle or dado height, except for the architraves above and a few columns that, together with those other features, frame vividly coloured architectural views of buildings, columns, landscape, garden scenes, religious statues, beyond, emphasizing expansion and grandeur, but including no humans and only a few birds on the short, window wall. This is also the technique in other unreconstructed rooms. For example, In another bedroom, known as Room M, the frescoes depict columns that appear to expand into another room, giving the sense of a much larger, almost unending, space. The facing long walls (19 ft or 5.8 m) of the Metropolitan cubiculum are mirror images of each other, possibly by transfer, with variations. In addition, each is divided into four panels by painted columns.

Distance in these paintings is built up through a series of orthogonal architectural surfaces, and indicated by overlap occlusion, foreshortening, diminution, pronounced aerial perspective, but without vanishing points. Modelling is indicated by side-shading with slight, selective cast shadow. Pompeian red in front planes, contrasting with the blue tone of the fainter, further planes, provides an additional effective cue for depth. The room had one, north-facing, outside window, through which pyroclastic flows from Vesuvius appear to have entered. As part of the sophisticated depictive scheme, the dado or lower parts of the walls are depicted as themselves, but in First Style. Ledges and niches there show near objects: "metal and glass vases on shelves and tables appearing to project out from the wall", playfully belying the common impression that perspective is always for depicting recession from the picture plane.[16] In other parts of the Villa there are brightly colored nonfigurative walls, in First Style, some of which are on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Louvre Museum.

Gallery

Villa della Pisanella

_(14750122396).jpg)

The villa was unearthed over several archaeological seasons, confirming the hypothesis of a villa rustica covering 1000 square metres with clearly defined residential sector and farm buildings.

In 1895 the remains of a vaulted box were discovered in the wine-pressing room of the villa. The box contained silver tableware consisting of 102 items and leather bag full of coins to the value of a thousand gold aurei. It is assumed that the objects were intentionally hidden in the storehouse before the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in AD 79. The last owner of the silver set was probably a woman named Maxima – a name written on many of the vessels.

Notes

- ↑ PompeiiinPictures: http://www.pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/RV/villas%20new.htm#Boscoreale

- ↑ https://sites.google.com/site/ad79eruption/boscoreale

- ↑ http://pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/VF/Villa_014.htm

- ↑ Hornblower, Simon and Antony Spawforth. Oxford Classical Dictionary. London: Oxford University Press, 1996. 254.

- ↑ http://pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/RV/villa%20regina%20boscoreale%20p1.htm

- ↑ "Roman Frescoes from Boscoreale: The Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Reality and Virtual Reality" Bergmann et al., The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Spring 2010

- ↑ "The Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Winter 1987-88: 17-36.

- ↑ Milne, Margerie J. "A Bronze Stamp from Boscoreale." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 09. 1930: 188-190.

- ↑ Pfrommer, Michael; Towne-Markus, Elana (2001). Greek Gold from Hellenistic Egypt. Los Angeles: Getty Publications (J. Paul Getty Trust). ISBN 0-89236-633-8, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ "Roman Frescoes from Boscoreale: The Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Reality and Virtual Reality" Bergmann et al., The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Spring 2010, p 14

- ↑ "The Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale" p. 29

- ↑ "The Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale" p. 31

- ↑ Rudolf Meyer, “The Conservation of the Frescoes from Boscoreale in the Metropolitan Museum, in Roman Frescoes from Boscoreale.

- ↑ Bettina Bergmann et al., Roman Frescoes from Boscoreale: The Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Reality and Virtual Reality (Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 62.4 [Spring 2010]). This, the most recent work on the Villa, is the main source for information not otherwise attributed.

- ↑ "The Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale" p. 17

- ↑ "The Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale" p. 21

Further Reading:

- Philippe de Montebello (1994). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Guide. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sources

- Hornblower, Simon; Antony Spawforth (1996). Oxford Classical Dictionary. London: Oxford University Press. p. 254. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- Milne, Margerie J. (1930). "A Bronze Stamp from Boscoreale". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 25 (09): 188–190. doi:10.2307/3255709. JSTOR 3255709.

- "The Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 45 (3): 17–36. Winter 1987–1988. doi:10.2307/3269140.

- Bettina Bergmann et al., Roman Frescoes from Boscoreale: The Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Reality and Virtual Reality (Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 62.4 [Spring 2010])

External links

![]()

- Official Pompeii site of the SANP

- https://sites.google.com/site/ad79eruption/boscoreale/villa-of-publius-fannius-synistor

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Guide, a collection catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art containing information on Villa Boscoreale (page 325)

- Official site of the National Archaeological Museum in Naples: themed collections for Pompeii

- Some of the best illustrations of art and artistic small finds many put back into their original find locations on pompeiiinpictures

- Romano-Campanian Wall-Painting