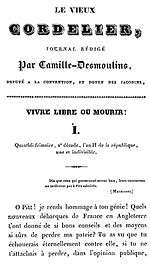

Le Vieux Cordelier

First issue of Le Vieux Cordelier | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Editor | Camille Desmoulins |

| Founded | 5 December 1793 |

| Political alignment |

Dantonism; Moderatism |

| Language | French |

| Ceased publication | 3 February 1794 |

| Headquarters | Paris, French Republic |

| Circulation | unknown |

Le Vieux Cordelier (French: [lə vjø kɔʁdəlje]) was a journal published in France between 5 December 1793 and 3 February 1794. Its radical criticism of ultra-revolutionary fervor and repression in France during the Reign of Terror contributed significantly to the downfall and execution of the Dantonists, among whom its author, the journalist Camille Desmoulins, numbered. It comprised seven numbers, of which six appeared; the seventh remained unpublished for some forty years.[1]

Camille Desmoulins

A French native born March 2, 1760, in Guise, France. Desmoulins' role as a journalist led him to the production of Le Vieux Cordelier. Desmoulins personally struggled in his attempts to become a lawyer; despite his acceptance in law school as well into parlement of Paris, Desmoulins found himself inadequate to continue his career as lawyer, primarily because of his unruly temper. Nevertheless, he still continued his struggle to contribute to a reconstructed government. As a Jacobin radical, Desmoulins was not the only one who contributed to these efforts. His close friends Maximilien Robespierre and Georges Danton played significant roles alongside him. This friendship lasted up until both Desmoulins and Danton (among fifteen other revolutionists), were put on trial for their contribution to the revolution, their executions exemplified the reign of terror tumbling down.[2]

The Document

Title

The title of the Vieux Cordelier ("Old Cordelier") refers to the Cordeliers Club, an influential revolutionary society that, from its relatively moderate origins under Danton, had come to be associated with ultra-revolutionary factions – principally the followers of journalist Jacques René Hébert. Desmoulins sought to ally his journal's arguments with the less extreme politics of the earlier, "old" Cordeliers, while simultaneously repudiating the violent, anti-religious Hébertists. In this goal, Desmoulins was supported by Maximilien Robespierre, who viewed the Vieux Cordelier's attacks on the Hébertists as an effective means of reducing the faction's power and popularity. However, later numbers of the journal introduced criticisms of the Revolutionary Tribunal, the Committee of Public Safety, and Robespierre himself.

Third Number

The third number of the Vieux Cordelier, appearing 25 Frimaire (15 December 1793), purported to quote without comment passages from the Annals of the Roman historian Tacitus concerning the oppressive reign of the emperor Tiberius. While more likely drawn from the Discourses on Tacitus published in 1737 by Thomas Gordon,[3] these terse portraits - describing a civilization turned sick by fear and brutality - were effective in drawing a powerful parallel between Rome under Tiberius and France during the Terror.

Fourth Number

The fourth number, published 30 Frimaire (20 December 1793), argued against the Law of Suspects, saying, "...in the Declaration of Rights there is no house of suspicion... there are no suspected persons, only those convicted of crimes fixed by the law."[4] It also appealed for a "Committee of Clemency" to counter the excesses of the Committee of Public Safety and Committee of General Security. So controversial were these views that Desmoulins was expelled from the Cordeliers Club and denounced at the Jacobin Club. Robespierre, hoping to present his friend "as an unthinking child who had fallen into bad company," recommended that the offending numbers of the journal be publicly burnt as an alternative to expelling Desmoulins from the Jacobins.[5] Initially Robespierre supported Camille's new project, as long as he believed it would lead to the end of the Herbertists. Eventually, the more popular the newspaper got the farther he felt Desmoulin from their initial purpose nevertheless, leading him to requesting the right to proofread anything before it was published.[2]

Fifth Number

In the fifth number, which appeared 16 Nivôse (5 January 1794) though dated 5 Nivôse (25 December 1793), Desmoulins addressed himself in a "justificatory discourse" to the Jacobins,[6] maintaining his calls for an end to the Terror. Shortly after this issue appeared, on 21 Nivôse (10 January), Desmoulins was expelled from the Jacobin Club.[7]

Sixth Number

The sixth number, though dated 10 Nivôse (30 December 1793), was further delayed due to the political concerns of its publisher[1] and did not appear until 15 Pluviôse (3 February 1794).[8] Though Desmoulins had rephrased his demands for a Committee of Clemency and called instead for a "Committee of Justice," and turned his attacks again against the politically acceptable target of Hébert, his criticism of the Terror continued. Dessene's hesitation to publish this number, then led to his decision to not move further and instead withhold the Seventh Number.

Seventh Number

The seventh number, written in late March, did not appear in Desmoulins' lifetime. Dessene's hesitation to publish the Sixth Number, then led to his decision to not move further and instead withhold the Seventh Number, mainly in fear of the reaction based on its political standpoint. Early in the morning of March 31, Desmoulin was arrested on a warrant issued by the Revolutionary Tribunal. Along with Danton, he was tried on charges of counter-revolutionary conspiracy and, on 5 April 1794, was executed by guillotine.

References

- Claretie, Jules. Camille Desmoulins and His Wife: Passages from the History of the Dantonists. London: Smith, Elder, & Co., 1876.

- Hammersley, Rachel. French Revolutionaries and English Republicans: The Cordeliers Club 1790-1794. Rochester: Boydell & Brewer Inc., 2005.

- Giovanni Tarantino, "Republicanism, Sinophilia, and Historical Writing Thomas Gordon (c. 1691–1750) and his ‘History of England’." Brepols Publishers, 2012.

- Methley, Violet. Camille Desmoulins: A Biography. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1915.

- Scurr, Ruth. Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution. New York: Owl Books, 2006.

- Weber, Caroline. Terror and Its Discontents: Suspect Words in Revolutionary France. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Notes

External links

- Le Vieux Cordelier online in Gallica, the digital library of the BnF.