Portal vein

| Portal vein | |

|---|---|

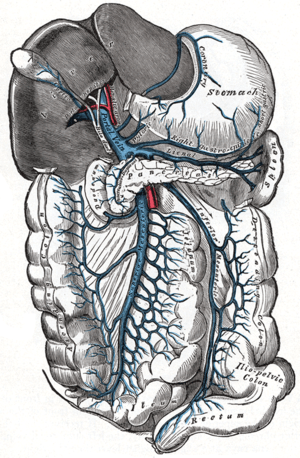

The portal vein and its tributaries. It is formed by the superior mesenteric vein, inferior mesenteric vein, and splenic vein. Lienal vein is an old term for splenic vein. | |

| Details | |

| Drains from | Gastrointestinal tract, spleen, pancreas |

| Source | splenic vein, superior mesenteric vein, inferior mesenteric vein |

| Drains to | liver sinusoid |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vena portae hepatis |

| MeSH | D011169 |

| TA | A12.3.12.001 |

| FMA | 50735 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The portal vein or hepatic portal vein is a blood vessel that carries blood from the gastrointestinal tract, gallbladder, pancreas and spleen to the liver. This blood contains nutrients and toxins extracted from digested contents. Approximately 75% of total liver blood flow is through the portal vein, with the remainder coming from the hepatic artery proper. The blood leaves the liver to the heart in the hepatic veins.

The portal vein is not a true vein, because it conducts blood to capillary beds in the liver and not directly to the heart. It is a major component of the hepatic portal system, one of only two portal venous systems in the body – with the hypophyseal portal system being the other.

The portal vein is usually formed by the confluence of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins and also receives blood from the inferior mesenteric, left and right gastric veins, and cystic veins.

Conditions involving the portal vein cause considerable illness and death. An important example of such a condition is elevated blood pressure in the portal vein. This condition, called portal hypertension, is a major complication of cirrhosis.

Structure

Measuring approximately 8 cm (3 inches) in adults,[1] the portal vein is located in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, originating behind the neck of the pancreas.[2]

In most individuals, the portal vein is formed by the union of the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein.[3] For this reason, the portal vein is occasionally called the splenic-mesenteric confluence.[2] Occasionally, the portal vein also directly communicates with the inferior mesenteric vein, although this is highly variable. Other tributaries of the portal vein include the cystic and the left and right gastric veins.[4]

Immediately before reaching the liver, the portal vein divides into right and left. It ramifies further, forming smaller venous branches and ultimately portal venules. Each portal venule courses alongside a hepatic arteriole and the two vessels form the vascular components of the portal triad. These vessels ultimately empty into the hepatic sinusoids to supply blood to the liver.[4]

Portacaval anastomoses

The portal venous system has several anastomoses with the systemic venous system. In cases of portal hypertension these anastamoses may become engorged, dilated, or varicosed and subsequently rupture.

Accessory hepatic portal veins

Accessory hepatic portal veins are those veins that drain directly into the liver without joining the hepatic portal vein. These include the paraumbilical veins as well as veins of the lesser omentum, falciform ligament, and those draining the gallbladder wall.[2]

Function

The portal vein and hepatic arteries form the liver's dual blood supply. Approximately 75% of hepatic blood flow is derived from the portal vein, while the remainder is from the hepatic arteries.[2]

Unlike most veins, the portal vein does not drain into the heart. Rather, it is part of a portal venous system that delivers venous blood into another capillary system, the hepatic sinusoids of the liver. In carrying venous blood from the gastrointestinal tract to the liver, the portal vein accomplishes two tasks: it supplies the liver with metabolic substrates and it ensures that substances ingested are first processed by the liver before reaching the systemic circulation. This accomplishes two things. First, possible toxins that may be ingested can be detoxified by the hepatocytes before they are released into the systemic circulation. Second, the liver is the first organ to absorb nutrients just taken in by the intestines. After draining into the liver sinusoids, blood from the liver is drained by the hepatic vein.

Clinical significance

Portal hypertension

Increased blood pressure in the portal vein, called portal hypertension, is a major complication of liver disease, most commonly cirrhosis.[5] A dilated portal vein (diameter of greater than 13 or 15 mm) is a sign of portal hypertension, with a sensitivity estimated at 12.5% or 40%.[6] On Doppler ultrasonography, the main portal vein (MPV) peak systolic velocity normally ranges between 20 cm/s and 40 cm/s.[7] A slow velocity of <16 cm/s in addition to dilatation in the MPV are diagnostic of portal hypertension.[7]

Clinical signs of portal hypertension include those of chronic liver disease: ascites, esophageal varices, spider nevi, caput medusae, and palmar erythema.[8]

Infection

Pylephlebitis is infection of the portal vein, usually arising from an infectious intra-abdominal process such as diverticulosis.[9][10]

References

- ↑ Harold M Chung; Chung, Kyung Won (2008). Gross anatomy. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 208. ISBN 0-7817-7174-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Plinio Rossi; L. Broglia (2000). Portal Hypertension: Diagnostic Imaging and Imaging-Guided Therapy. Berlin: Springer. p. 51. ISBN 3-540-65797-5.

- ↑ Benjamin L. Shneider; Sherman, Philip M. (2008). Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disease. Connecticut: PMPH-USA. p. 751. ISBN 1-55009-364-9.

- 1 2 3 Henry Gray (1901). Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical (16 ed.). Philadelphia: Lea Brothers. p. 619.

- ↑ Dooley, James; Sherlock, Sheila (2002). Diseases of the liver and biliary system. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-05582-0.

- ↑ Al-Nakshabandi NA (2006). "The role of ultrasonography in portal hypertension". Saudi J Gastroenterol.

- 1 2 Iranpour, Pooya; Lall, Chandana; Houshyar, Roozbeh; Helmy, Mohammad; Yang, Albert; Choi, Joon-Il; Ward, Garrett; Goodwin, Scott C (2016). "Altered Doppler flow patterns in cirrhosis patients: an overview". Ultrasonography. 35 (1): 3–12. doi:10.14366/usg.15020. ISSN 2288-5919.

- ↑ Key Topics in General Surgery (2 ed.). Informa Healthcare. 2002. ISBN 1-85996-164-9.

- ↑ Plemmons RM, Dooley DP, Longfield RN (November 1995). "Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein (pylephlebitis): diagnosis and management in the modern era". Clin. Infect. Dis. 21 (5): 1114–20. doi:10.1093/clinids/21.5.1114. PMID 8589130.

- ↑ Perez-Cruet MJ, Grable E, Drapkin MS, Jablons DM, Cano G (May 1993). "Pylephlebitis associated with diverticulitis". South. Med. J. 86 (5): 578–80. doi:10.1097/00007611-199305000-00020. PMID 8488411.

Additional images

Human embryo with heart and anterior body-wall removed to show the sinus venosus and its tributaries.

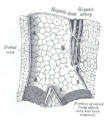

Human embryo with heart and anterior body-wall removed to show the sinus venosus and its tributaries. Section across portal triad of pig.

Section across portal triad of pig. Longitudinal section of a small portal vein and canal.

Longitudinal section of a small portal vein and canal.- Hepatic portal vein.Plastination technique.

- Hepatic portal vein.Abdominal cavity.Deep dissection.

- Hepatic portal vein.Visceral surface of liver.

External links

- Anatomy photo:38:12-0109 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Stomach, Spleen and Liver: The Visceral Surface of the Liver"

- Anatomy image:7959 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy image:8565 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy image:8697 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Cross section image: pembody/body8a—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- figures/chapter_30/30-2.HTM: Basic Human Anatomy at Dartmouth Medical School