United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean

| |

ECLAC headquarters in Santiago, Chile | |

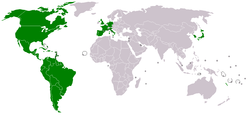

Map showing United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean members` | |

| Abbreviation | ECLAC / CEPAL |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1948 |

| Type | Primary Organ - Regional Branch |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters |

|

Head |

|

Parent organization | ECOSOC |

| Website | English version |

The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, known as ECLAC, UNECLAC or in Spanish and Portuguese CEPAL, is a United Nations regional commission to encourage economic cooperation. ECLAC includes 45 member States (20 in Latin America, 13 in the Caribbean and 12 from outside the region), and 13 associate members which are various non-independent territories, associated island countries and a commonwealth in the Caribbean. ECLAC publishes statistics covering the countries of the region[2] and makes cooperative agreements with nonprofit institutions.[3] ECLAC's headquarters is in Santiago, Chile.

ECLAC was established in 1948 as the UN Economic Commission for Latin America,[4] or UNECLA. In 1984, a resolution was passed to include the countries of the Caribbean in the name.[5] It reports to the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

Member states

The member states are Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, France, Germany, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, South Korea, Spain, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, United States of America, Uruguay, and Venezuela. The associate members are Anguilla, Aruba, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Curaçao, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Montserrat, Puerto Rico, Sint Maarten, Turks and Caicos Islands, and United States Virgin Islands. [6]

Locations

- Santiago, Chile (headquarters)

- Mexico City, Mexico (Central American subregional headquarters)

- Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago (Caribbean subregional headquarters)

- Buenos Aires, Argentina (country office)

- Brasília, Brazil (country office)

- Montevideo, Uruguay (country office)

- Bogotá, Colombia (country office)

- Washington, DC, United States of America (liaison office)

Executive Secretaries

| Name | Country | Served |

|---|---|---|

| Alicia Bárcena Ibarra | July 2008 – present | |

| José Luis Machinea | December 2003 - June 2008 | |

| José Antonio Ocampo | January 1998 – August 2003 | |

| Gert Rosenthal | January 1988 – December 1997 | |

| Norberto González | March 1985 – December 1987 | |

| Enrique V. Iglesias | April 1972 – February 1985 | |

| Carlos Quintana | January 1967 – March 1972 | |

| José Antonio Mayobre | August 1963 – December 1966 | |

| Raúl Prebisch | May 1950 – July 1963 | |

| Gustavo Martínez Cabañas | December 1948 – April 1950 |

In relation to development discourse and dependency theory

The formation of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America was crucial to the beginning of "Big D development". Many economic scholars attribute the founding of ECLA and its policy implementation in Latin America for the subsequent debates on structuralism and dependency theory. Although forming in the post-war period, the historic roots of the ECLA trace back to political movement made long before the war had begun.

Before World War II, the perception of economic development in Latin America was formulated primarily from colonial ideology. This perception, combined with the Monroe Doctrine that asserted the United States as the only foreign power that could intervene in Latin American affairs, led to substantial resentment in Latin America. In the eyes of those living in the continent, Latin America was considerably economically strong; most had livable wages and industry was relatively dynamic.[7] This concern of a need for economic restructuring was taken up by the League of Nations and manifested in a document drawn up by Stanley Bruce and presented to the League in 1939. This in turn strongly influenced the creation of the United Nations Economic and Social Committee in 1944. Although it was a largely ineffective policy development initially, the formation of the ECLA proved to have profound effects in Latin America in following decades. For example, by 1955, Peru was receiving $28.5 million in loans per ECLA request.[8] Most of these loans were utilized as means to finance foreign exchange costs, creating more jobs and heightening export trade. To investigate the extent to which this aid was supporting industrial development plans in Peru, ECLA was sent in to study its economic structure. In order to maintain stronghold over future developmental initiatives, ECLA and its branches continued providing financial support to Peru to assist in the country’s general development.[7]

The terms of trade at this time, set by the United States, introduced the concept of "unequal exchange" in that the so-called "North" mandated prices that allowed them a greater return on its own resources than that of the "South's". Thus, although the export sector had grown during this time, certain significant economic and social issues continued to threaten this period of so-called stability. Although real income was on the rise, its distribution was still very uneven. Social problems were still overwhelmingly prevalent; large portions of the population were unnourished and without homes, and the education and health system were inept.[7]

See also

- United Nations System

- eLAC eLAC2007, eLAC2010 and eLAC2015: Strategies for the Information Society in Latin America and the Caribbean

References

- ↑ eclac.cl, ECLAC: Office of the Executive Secretary

- ↑ CEPALSTAT Archived May 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. page at official ECLAC site

- ↑ ECLAC signed a cooperation agreement to promote science and technology in the region (with Brazilian Center for Strategic Studies and Management) at ECLAC.org

- ↑ Cypher, James M.; Dietz, James L. (2009). The process of economic development. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77103-0.

- ↑ ABOUT ECLAC at official ECLAC site

- ↑ "ABOUT ECLAC – Member States and associate members of ECLAC". CEPAL. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 Vandendries, Rene (1967). Foreign Trade and the Economic Development of Peru. Iowa State University.

- ↑ Kofas, Jon (1996). Foreign Debt and Underdevelopment: U.S.-Peru Economic Relations, 1930-1970. Lanham: U of America.

Bibliography

- Paul Berthoud, A Professional Life Narrative, 2008, worked with CEPAL-ECLAC and offers testimony from the inside of the early years of the organization.

- José Briceño Ruiz, María Liliana Quintero Rizzuto and Dyanna de Benítez (June 2013). "The ECLAC's structuralist thinking on development and Latin American integration: reflections on the contemporary relevance". Aportes para la Integración Latinoamericana (in Spanish). XIX (28): 1–324. ISSN 1667-8613. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to ECLAC. |