Ukase

An ukase, or ukaz (/juːˈkeɪs/;[1] Russian: указ [ʊˈkas], formally "imposition"), in Imperial Russia, was a proclamation of the tsar, government,[2] or a religious leader (patriarch) that had the force of law. "Edict" and "decree" are adequate translations using the terminology and concepts of Roman law.

From the Russian term, the word ukase has entered the English language with the meaning of "any proclamation or decree; an order or regulation of a final or arbitrary nature".[1]

History

Prior to the 1917 October Revolution, the term applied in Russia to an edict or ordinance, legislative or administrative, having the force of law. A ukase proceeded either from the emperor or from the senate, which had the power of issuing such ordinances for the purpose of carrying out existing decrees. All such decrees were promulgated by the senate. A difference was drawn between the ukase signed by the emperor’s hand and his verbal ukase, or order, made upon a report submitted to him.[3]

After the Revolution, a government proclamation of wide meaning was called a "decree" (Russian: декрет, dekret); more specific proclamations were called ukaz. Both terms are usually translated as "decree".

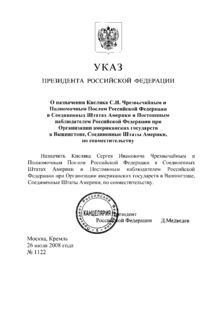

Executive Order of the President of Russia

According to the Russian Federation's 1993 constitution, an ukaz is a Presidential decree. The English term "Executive Order" is also used by the official website as an equivalent of the Russian ukaz.[4]

As normative legal acts, such ukazes have a status of by-law in the hierarchy of legal acts (along with a Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation, instructions and directions of other officials). Presidential decrees may not alter the regulations of existing legal sources - Russia's international agreements, the Constitution of Russia, Federal Constitutional Laws, Federal Laws and laws of Russian regions - and may be superseded by any of these laws. For example, thanks to Article 15 of the Constitution of Russia, the European Convention on Human Rights, as an international document, has higher status than any Russian law or presidential executive order.[5]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 OED staff 1989.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

- ↑

- ↑ See in Russian, in English

- ↑ "Universally recognized principles and norms of international law as well as international agreements of the Russian Federation should be an integral part of its legal system. If an international agreement of the Russian Federation establishes rules, which differ from those stipulated by law, then the rules of the international agreement shall be applied."

References

- OED staff (1989). "ukase, n." (Second ed.). Earlier version first published in New English Dictionary, 1921.

External links

![]()