Twelve Articles

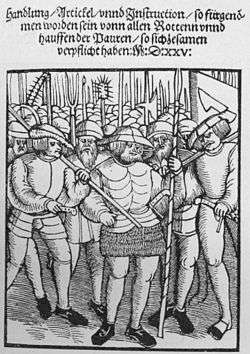

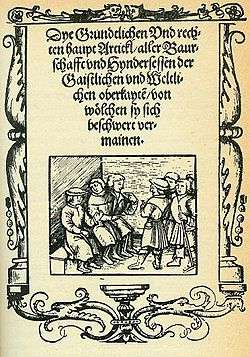

The Twelve Articles were part of the peasants' demands of the Swabian League during the German Peasants' War of 1525. They are considered the first draft of human rights and civil liberties in continental Europe after the Roman Empire. The gatherings in the process of drafting them are considered to be the first constituent assembly on German soil.[1][2][3][4][5]

Incidents

On 6 March 1525 about 50 representatives of the Upper Swabian Peasants Groups (of the Baltringer Mob, the Allgäuer Mob, and the Lake Constance Mob), met in Memmingen to deliberate upon their common stance against the Swabian League. One day later and after difficult negotiations, they proclaimed the Christian Association, an Upper Swabian Peasants' Confederation. The peasants met again on 15 and 20 March 1525 in Memmingen and, after some additional deliberation, adopted the Twelve Articles and the Federal Order (Bundesordnung).

The Articles and the Order are only examples among many similar programmes developed during the German Peasants' War that were published in print. The Twelve Articles in particular were printed over 25,000 times within the next two months, a tremendous print run for the 16th century. Copies quickly spread throughout Germany. Since the two texts were not developed any further in the course of the German Peasants' War, some sources speak of the meeting in Memmingen as a constitutional peasant assembly.[6]

Summary of the Twelve Articles

- Every municipality shall have the right to elect and remove a preacher if he behaves improperly. The preacher shall preach the gospel simply, straight and clearly without any human amendment, for, it is written, that we can only come to God by true belief.

- The preachers shall be paid from the great tithe. A potential surplus shall be used to pay for the poor and the war tax. The small tithe shall be dismissed, for it has been trumped-up by humans, for the Lord, our master, has created the cattle free for mankind.

- It has been practice so far, that we have been held as villein, which is pitiful, given that Christ redeemed all of us with his precious bloodshed, the shepherd as well as the highest, no one excluded. Therefore, it is devised by the scripture, that we are and that we want to be free.

- It is unfraternal and not in accordance with the word of God that the simple man does not have the right to catch game, fowls, and fish. For, when God our master created man, he gave him power over all animals, the bird in the air and the fish in the water.

- The high gentlemen have taken sole possession of the woods. If the poor man needs something, he has to buy it for double money. Therefore, all the woods that were not bought (relates to former community woods, which many rulers had simply appropriated) shall be given back to the municipality so that anybody can satisfy his needs for timber and firewood thereof.

- The matter of excessive services demanded of us should be properly looked into as we are only required to serve according to God

- The nobility shall not force more services or dues from the peasant without payment. The peasant should help the lord when it is necessary and at proper times.

- Many properties are not worth the rent demanded. Honest men shall inspect these properties and fix a rent in accordance with justice

- There are constantly new laws being made. One does not punish according to the offence but at discretion (raising fines and arbitrary punishment was common). It is our opinion that we shall be judged according to the case's merits, and not with partiality

- Several have appropriated meadows and acres (community land that was at the disposition of all members), that belong to the municipality. Those we want back to our common hands.

- The “Todfall” (a sort of inheritance tax) shall be abolished altogether and never again shall widows and orphans be robbed contrary to God and honour.

- It is our decision and final opinion that if one or several of the articles mentioned herein were not in accordance with the word of God, those we shall refrain from if it is explained to us on the basis of the scripture. If several articles were already granted to us and it emerged afterwards that they were ill, they shall be dead and null. Likewise, we want to have reserved that if even more articles are found in the writ that were against God and a grievance to though neighbour.

The Federal Order (Bundesordnung)

The Federal Order reached high print run as well and was probably particularly popular with the peasants, since it provided a model for a federal social order based on the municipality. Peasants’ communities were found to have been organised pursuant to this in the Black Forest, the Alsace and in Franconia.

Roots of the Twelve Articles

The roots of the Twelve Articles are disputed. Some sources attribute them to the Peasants Leader (Bauernkanzler) Wendel Hipler. Normally they are attributed to the reformer Sebastian Lotzer from Memmingen, who had possibly broadened already existing texts together with Christoph Schappeler.

On 16 February 1525 about 25 villages pertaining to the city of Memmingen rebelled, and in view of their economic condition and the general political situation, demanded considerable improvements with the city council. The complaints touched subjects like peonage, land regime, easements on the woods and the commons as well as ecclesiastical requirements. The peasants wanted reforms on a broad front. The city had set up a committee of villagers and expected to see a long checklist of specific demands. Very unexpectedly though, the peasants delivered a uniform, fundamental declaration made up of twelve articles. Many of those demands did subsequently not prevail in the city council, but one can assume, that the articles of the ordines provinciales una congregati (the representatives of the territory) of Memmingen had become the basis of discussion for the Twelve Articles agreed on by the Upper Swabian Peasants Confederation of 20 March 1525.

It is well possible that Joß Fritz’s demands, which he had raised during the so-called Bundschuh movement in 1513 influenced the articles of the representatives of the territory of Memmingen and thereby also had their influence on the Twelve Articles.

Martin Luther and the Twelve Articles

The peasants had to burden the many encumbrances they were charged with and in Martin Luther’s and the reformation’s stance they saw the affirmation that most of those were not provided for by the will of God.

But Luther was not happy with the peasants’ revolts and their invoking him. Possibly he also saw their negative effect on the Reformation as a whole. He called upon the peasants and urged them to keep peace. He also wrote to the gents:

“They set up twelve articles which of some are so just, that they do shame to you before God and world. But almost all of them are in their favour and not drawn up to the best. […] But it is unbearable to tax and slave-drive people like this forever.”

In May 1525 Luther’s script "Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants" appeared, in which he took sides for the authorities and, fearing for the godly order, called for the peasants’ destruction. It was specifically caused by the so-called “Weinsberger Bluttat”, the peasants under Jäcklein Rohrbach killing the High Governor, count Ludwig Helferich of Helfenstein and his followers, after having seized the city and the castle.

Continued effect

The fundamental ideas laid down in these demands seems to have lasted longer than their main fighters and representatives.

A direct comparison with the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 yields some equivalence in the motives and the implementation into the text. The results of the French Revolution starting in 1789 in the form of a modern state, that is a republic, sees quite some of the peasants’ points implemented.

In the following 300 years the peasants rarely rebelled. Only with the Revolution of March 1848/49 (Märzrevolution), the peasants’ objectives as formulated in the Twelve Articles of 1525 were finally implemented.

The second Vatican Council of 1965 defined the “supreme principle” of the reform on the liturgy to allow for the “conscious, active and comprehensive participation of the believers” in the liturgy of the church. In this context the respective popular language was added to the thitherto authoritative Latin as the language of the liturgy.

Literature

- Günther Franz: Die Entstehung der "Zwölf Artikel" der deutschen Bauernschaft, in: Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 36 (1939), S. 195-213.

- Peter Blickle: Nochmals zur Entstehung der Zwölf Artikel, in: Ders. (Hrsg.), Bauer, Reich, Reformation. Festschrift für Günther Franz zum 80. Geburtstag, Stuttgart 1982, S. 286-308.

- Ders.: Die Revolution von 1525, München 31993. ISBN 3-486-44263-5

- Ders.: Die Geschichte der Stadt Memmingen. Von den Anfängen bis zum Ende der Reichsstadt, Stuttgart 1997. ISBN 3-8062-1315-1

- Martin Brecht: Der theologische Hintergrund der Zwölf Artikel der Bauernschaft in Schwaben von 1525. Christoph Schappelers und Sebastian Lotzers Beitrag zum Bauernkrieg, in: Heiko A. Obermann (Hrsg.), Deutscher Bauernkrieg 1525 (Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 85, 1974, Heft 2) 1974, S. 30-64 (178-208).

- Oman, C. W. C. "The German Peasant War of 1525." The English Historical Review 5, no. 17 (1890): 65-94. . (includes English text of the Twelve Articles)

- Sea, Thomas F. "The German Princes' Responses to the Peasants' Revolt of 1525." Central European History 40, no. 2 (2007): 219-40. .

- Günter Vogler: Der revolutionäre Gehalt und die räumliche Verbreitung der oberschwäbischen Zwölf Artikel, in: Peter Blickle (Hrsg.), Revolte und Revolution in Europa )Historische Zeitschrift, Beiheft 4 NF), München 1975, S. 206-231.

- Ernst Walder: Der politische Gehalt der Zwölf Artikel der deutschen Bauernschaft von 1525, in: Schweizer Beiträge zur Allgemeinen Geschichte 12 (1954), S. 5-22.

References

- ↑ "Die Zwölf Artikel und Memmingen auf memmingen.de" (in German). Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ↑ Peter Blickle: Die Geschichte der Stadt Memmingen, von den Anfängen bis zum Ende der Reichsstadtzeit, S. 393 ff.

- ↑ Zwölf Artikel und Bundesordnung der Bauern, Flugschrift "An die versamlung gemayner pawerschafft", Stadtarchiv Memmingen, Materialien zur Memminger Stadtgeschichte, Reihe A, H. 2, S. 1, S. 3 ff.

- ↑ Unterallgäu und Memmingen, Edition Bayern, Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, 2010, S. 60

- ↑ Memminger Stadtrecht, Satzung der Stadt Memmingen über den Memminger Freiheitspreis 1525, Präambel

- ↑ Peter Blickle: Die Geschichte der Stadt Memmingen, von den Anfängen bis zum Ende der Reichsstadtzeit, Stuttgart 1997, S. 393.

External links

- The original text of the Twelve Articles in German by the city of Memmingen

- Translation by marxist.org

- Translation by German History in Documents and Images; Volume 1. From the Reformation to the Thirty Years’ War, 1500 - 1648, Grievances and Demands - The Twelve Articles of the Swabian Peasants (February 27 - March 1, 1525)