Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Canada)

| Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada | |

| Commission overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | June 2, 2008 by the parties of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement |

| Headquarters | 1500-360 Main Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba |

| Website |

www |

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

|

History

|

|

Culture

|

|

Demographics

|

|

Religions |

|

Index

|

|

Wikiprojects Portal

WikiProject

First Nations Inuit Métis |

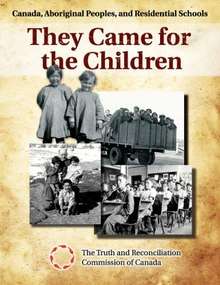

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) was a truth and reconciliation commission organized by the parties of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. The Commission was officially established on June 2, 2008 with the purpose of documenting the history and impacts of the Indian residential school. It provided former residential school attendees an opportunity to share their experiences during public and private meetings held across the country.

In June 2015, the TRC released an Executive Summary of its findings along with 94 "calls to action" regarding reconciliation between Canadians and Indigenous peoples. The Commission officially concluded in December 2015 with the publication of a multi-volume report that concluded the school system amounted to cultural genocide. The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, which opened in November 2015, is home to the research, documents, and testimony collected during the course of the TRC's operation.

Background

The TRC was established as one of the mandated aspects of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.[1][2] The commission was founded as an arms-length organization with a mandate of documenting the history and impacts of the residential school system. As part of this work the TRC spent six years travelling to different parts of Canada to hear the testimony of approximately six thousand Indigenous people who were taken away from their families and placed in residential schools as children.[3]

The mandate of the TRC included hosting seven national reconciliation events, collecting all relevant archival documents relating to the residential schools from church and government bodies, collecting statements from survivors, and overseeing a commemoration fund to support community reconciliation events.[4] The TRC's mandate emphasized preserving and exposing the true history of residential schools.[5]

In March 2008, Indigenous leaders and church officials embarked on a multi-city 'Remembering the Children' tour to promote activities of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[6] On January 21–22, 2008, the King's University College of Edmonton, Alberta, held an interdisciplinary studies conference on the subject of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. On June 11 of the same year, Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized for the role of past governments in administration of the residential schools.[7]

The commission's mandate was originally scheduled to end in 2014, with a final event in Ottawa. However, it was extended to 2015 as numerous records related to residential schools were provided to the commission in 2014 by Library and Archives Canada following a January 2013 order of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.[8] The commission needed additional time to review these documents. The commission held its closing event in Ottawa from May 31 to June 3, 2015, including a ceremony at Rideau Hall with Governor General David Johnston.

Commission name

The Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was named in a similar fashion to the commissions by the same name in Chile in 1990 and South Africa in 2001.[9] In this context reconciliation means: the act of restoring a once harmonious relationship.[10] The Commission came under criticism for using the term 'reconciliation' in their name, as it implies that there was once a harmonious relationship between settlers and Indigenous peoples that is being restored, while that relationship may never have existed in Canada.[11]:35 The use of the term reconciliation perpetuates that myth by continuing to deny "the existence of pre-contact Aboriginal sovereignty".[11]:35

Commission staff

Justice Harry S. Laforme of the Ontario Court of Appeal was named to chair the Commission. He resigned on October 20, 2008, citing insubordination by the two other commissioners, Claudette Dumont-Smith and Jane Brewin Morley. Laforme said they wanted to focus primarily on uncovering and documenting truth while he wanted to also have an emphasis on reconciliation between aboriginal and non-aboriginal Canadians. In addition: "The two commissioners are unprepared to accept that the structure of the commission requires that the commission's course is to be charted and its objectives are to be shaped ultimately through the authority and leadership of its chair."[12] Although Dumont-Smith and Morley denied the charge and initially stayed on,[13] both resigned in January 2009.

On June 10, 2009 Murray Sinclair was appointed to replace Laforme as chairperson of the TRC. Marie Wilson, a senior executive with the Workers' Safety and Compensation Commission of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, and Wilton Littlechild, former Conservative Member of Parliament and Alberta regional chief for the Assembly of First Nations, were appointed to replace commissioners Dumont-Smith and Morley.[14]

Results

Calls to action

In June 2015 the TRC released a summary report of its findings and "94 Calls to Action" to "redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation". These were divided into two categories: "Legacy" and "Reconciliation":[15] Legacy Redressing the harms resulting from the Indian residential schools, the proposed actions are identified in the following sub-categories:

- Child welfare - Residential schools often served as foster homes rather than educational centres. According to a 1953 survey, 4,313 children of 10,112 residential school children were described as either orphans or originated from broken homes.[16] The sole residential school in Canada's Atlantic Provinces, in Shubenacadie, N.S., was one such school, taking in children whom child welfare agencies believed to be at risk. By 2011, 3.6% of all First Nations children under the age of 14 were in foster care, compared to 0.3% for non-aboriginal children.[17] In 2012, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child voiced its concern on Canada's removal of Indigenous children from their families as a 'first resort'.[18]

- Education - It has been claimed that the education system for residential schools operated under the assumption that aboriginals were intellectually and culturally inferior, but documented evidence suggests otherwise. Prior to the establishment of the IRS system, a number of Indigenous had already received a non-Indigenous education in earlier mission schools. However, because of limited funds, a shortage of trained teachers, and an emphasis on manual labour, a good many students in the IRS system did not progress beyond a rudimentary education. When residential schools were phased out, Indigenous youth enrolled in provincial schools dropped out in large numbers. The calls to action are to address the current school completion rates and the income gap between the aboriginals and non-aboriginals. In addition, the calls to actions request to eliminate the discrepancy in funding of schools on and off reserves, where children have had to leave their families behind to pursue high-school education or further education.

- Language and Culture - In many schools, children in residential schools were not allowed to speak their native languages or practice their culture, partly to encourage the use of English but also in an effort by the government to assimilate the children into non-aboriginal society. While there was never a government policy regarding the suppression of native languages, individual school administrators determined their own policy regarding enforcement of English in the schools. According to UNESCO, 36% of Canada's Indigenous languages are listed as being critically endangered.[19] The calls to action request increased funding for educating children in Indigenous languages and also request that post-secondary institutions provide degrees and diplomas in Indigenous languages.

- Health - Health care for IRS students varied considerably between schools and between different decades. After the 1940s, health facilities and health care workers became more prevalent. Some schools had a nurse on staff and an infirmary, with doctors who paid visits. Testimony before the TRC reveals that a great many Aboriginal children were subjected to sexual and physical abuse while attending a residential school. It is often claimed that the effects of the trauma have been passed on to the children of those students, but there is also evidence that this intergenerational effect is significantly less than claimed. Today, due to the isolated locations of many Aboriginal communities, there continues to be a significant lack of health services available to these communities. The calls to action are meant to address the health outcomes for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians.

- Justice - When the Canadian legal system was tasked with investigating abuse claims, few prosecutions resulted from police investigations. In many cases, the federal government and the RCMP actually compromised the investigations. Given the statutes of limitations, many acts of abuse have gone unpunished because the children did not have the means or possess the knowledge to seek justice for their abuses. The calls to action seek to extend the statutes of limitations and reaffirm the independence of the RCMP.

Reconciliation To bring the federal and provincial governments and Indigenous nations of Canada into a reconciled state for the future, the proposed actions are identified in the following sub-categories:

- Canadian governments and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People

- Royal proclamation and covenant of reconciliation

- Settlement agreement parties and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Equity for Aboriginal people in the legal system

- National council for reconciliation

- Professional development and training for public servants

- Church apologies and reconciliation

- Education for reconciliation

- Youth programs

- Museums and archives

- Missing children and burial information

- National centre for truth and reconciliation

- Commemoration

- Media and reconciliation

- Sports and reconciliation

- Business and reconciliation

- Newcomers to Canada

In 2016 and 2017 historian Ian Mosby evaluated how many of the calls to action had been completed at the one year and two year anniversary marks. In 2016 he concluded that only five calls were complete and three calls were partially complete, leaving 86 calls unmet.[20] In 2017 his evaluation showed that only 7 of the 94 calls have been completed.[21]

In 2018 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation established the Beyond 94 website to track the status of each call to action.[22] As of March 2018, 10 were marked as completed, 15 were in-progress with projects underway, 25 had projects proposed, and 44 were unmet.[23]

Final report

In December 2015 the TRC released a Final Report, titled "Honouring the Truth, Reconciling the Future." The report was based upon primary source research undertaken by the commission and testimonies collected from residential school survivors during TRC events. The report noted that an estimated 150,000 children attended residential schools during its 120-year history and an estimated 3200 of those children died in the residential schools.[24] From the 70,000 former IRS students still alive, there were 31,970 sexual or serious sexual assault cases resolved by independent assessment process, and 5,995 claims were still in progress as of the report's release.[24]

The TRC concluded that the removal of children from the influence of their own culture with the intent of assimilating them into the dominant Canadian culture amounted to cultural genocide.[25]:1 The ambiguity of the TRC's phrasing allowed for the interpretation that physical and biological genocide also occurred. The TRC was not authorized to conclude that physical and biological genocide occurred, as such a finding would imply a legal responsibility of the Canadian government that would be difficult to prove. As a result, the debate about whether the Canadian government also committed physical and biological genocide against Indigenous populations remains open.[26][27]

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) was established at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, as an archive to hold the research, documents, and testimony collected by the TRC during its operation.[28] The NCTR opened to the public in November 2015 and holds more than five million documents relating to the legacy of residential schools in Canada.[28]

Criticisms

A number of critiques about the TRC have been put forward by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous writers, ranging from its scope and motivating framework to its methodology and conclusions. Professor Glen Coulthard, a member of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, has argued that the TRC's focus on the residential school system positioned reconciliation as a matter of "overcoming a 'sad chapter' in [Canadian] history,"[29]:125 which failed to recognize the ongoing nature and impact of colonialism. For Coulthard reconciliation being tied solely to the residential school system and actions of the past explains why Prime Minister Stephen Harper was able to apologize for the system in 2008 and, a year later, claim that there is no history of colonialism in Canada.[30] Professors Brian Rice, a member of the Mohawk Nation, and Anna Snyder agree with Coulthard's critique of the focus on residential schools as the singular issue to reconcile noting that the schools were only "one aspect of a larger project to absorb or assimilate Aboriginal people".[31]:51

Many writers have observed the way the TRC historicizes the events of colonialism and fails to emphasize that uneven Indigenous-settler relationships are perpetual and ongoing .[32] Historicizing is further evident in the TRC's 'Principles of Reconciliation' where reconciliation is framed as grappling with harms of the past. [33] This is problematic because it implies that colonialism is not ongoing and is not part of current government policy.[29] Because of this historicizing, the TRC concentrated its efforts largely on 'psychological' healing through the gathering and airing of stories; however, it lacked significant institutional change, particularly change to the kinds of government institutions involved in residential schools and other forms of colonial domination.[29]:121

Another problematic premise of the Commission is that society is only allowed "reconciliation on terms still largely dictated by the state".[29]:127 Rather than allowing a grassroots movement to gain traction or forms of 'moral protest' to develop, it was the government that initiated the process of reconciliation and set the terms of it, thus it is still the colonial power that is dictating the terms of their colonial subjects' healing.[29]:167 This is clearly proven in the way the government "[imposed] a time limit on 'healing'"; so that this event can be reconciled and then moved on from.[32]:36 The approach by the Commission to engage with Indigenous peoples when and how it is most convenient for settlers can be seen as "yet another form of settler colonialism".[34]:3 Because Indigenous "recognition and reconciliation, from a Canadian perspective, [is] focused only on the wrongs of the past, and the situation as it exists today is ignored".[30]

Unlike the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, the Canadian commission had no power to offer known perpetrators of abuse the possibility of amnesty in exchange for honest testimony about any abuses that may have been committed. Nor were perpetrators held accountable via the commission. The Canadian commission heard primarily from former students.[25]

Questioning of findings

Hymie Rubenstein, a retired professor of anthropology, and Rodney A. Clifton, professor emeritus of education and a residential school supervisor in the 1960s, held that, while the residential school program had been harmful to many students, the commission had shown "indifference to robust evidence gathering, comparative or contextual data, and cause-effect relationships," which resulted in the commission's report telling "a skewed and partial story".[35]

The Truth and Reconciliation Report did not compare its findings with rates and causes of mortality among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children attending public schools. Rubenstein and Clifton noted that the report also failed to consider Indian residential schools were typically located in rural areas far from hospitals, making treatment more difficult to acquire.[36]

In March 2017, Lynn Beyak, a Conservative member of the Senate Standing Committee of Aboriginal Peoples, voiced disapproval of the final TRC report, saying that it had omitted an "abundance of good" that was present in the schools.[37][38] Although Beyak's right to free speech was defended by some Conservative senators, her comments were widely criticized, including by Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett and leader of the New Democratic Party Tom Mulcair.[39] The Anglican Church also raised concerns stating in a release co-signed by bishops Fred Hiltz and Mark MacDonald: "There was nothing good about children going missing and no report being filed. There was nothing good about burying children in unmarked graves far from their ancestral homes."[40][41] In response, the Conservative Party leadership removed Beyak from the Senate committee underscoring that her comments did not align with the views of the party.[39]

Legacy

In August 2018, the Royal Canadian Geographical Society announced the release of the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, an encyclopedia with content including information about indigenous lands, languages, communities, treaties, and cultures, and topics such as the Canadian Indian residential school system, racism, and cultural appropriation.[42] It was created to address the Calls to Action, among them the development of "culturally appropriate curricula" for Aboriginal Canadian students.

See also

References

- ↑ "FAQs: Truth and Reconciliation Commission". CBC News. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Schedule N of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement". Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ "The Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission-prb0848e". lop.parl.ca. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ Canada, Library and Archives (May 3, 2017). "Library and Archives Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission Web Archive". Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ Mark Kennedy, "At least 4,000 aboriginal children died in residential schools, commission finds", Ottawa Citizen, Canada.com, January 3, 2014, accessed October 18, 2015

- ↑ "Indian, church leaders launch multi-city tour to highlight commission". CBC. March 2, 2008. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Statement of apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools". Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Government of Canada. June 11, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Huge number of records to land on Truth and Reconciliation Commission's doorstep". CBC. April 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Truth and Reconciliation Commission". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Reconciliation". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Garneau, David (2012). "Imaginary Spaces of Conciliation and Reconciliation" (PDF). West Coast Line. 46 (2). Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ↑ Judge at head of residential school investigation resigns, CBC, October 18, 2008, archived from the original on November 3, 2012, retrieved October 20, 2008

- ↑ Joe Friesen, Jacquie McNish, Bill Curry (October 22, 2008). "Native leaders divided over future of residential schools panel". The Globe and Mail (Last updated March 13, 2009). Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ↑ New commissioners for native reconciliation, CBC, June 10, 2009, retrieved June 16, 2009

- ↑ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (PDF) (Report). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

In order to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission makes the following calls to action.

- ↑ TRC, NRA, INAC – Resolution Sector – IRS Historical Files Collection – Ottawa, file 6-21-1, volume 2 (Ctrl #27-6), H. M. Jones to Deputy Minister, December 13, 1956. [NCA-001989-0001]

- ↑ Canada, Statistics Canada, Aboriginal People in Canada, 19

- ↑ United Nations, Convention on the Rights of the Child, Concluding observations, 12–13

- ↑ Moseley and Nicolas, Atlas of the World's Languages, 117

- ↑ "TRC calls to action update after 500-plus days since Trudeau's promise". windspeaker.com. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Curious about how many of the TRC's calls to actions have been completed? Check Ian Mosby's Twitter | CBC Radio". CBC. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Beyond 94: Where is Canada at with reconciliation? | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Beyond 94 Truth and Reconciliation in Canada". CBC. March 19, 2018.

- 1 2 Schwartz, Daniel (June 2, 2015). "Truth and Reconciliation Commission: By the numbers". CBC News. CBC. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- 1 2 "Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada" (PDF). National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. May 31, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ MacDonald, David B. (October 2, 2015). "Canada's history wars: indigenous genocide and public memory in the United States, Australia and Canada". Journal of Genocide Research. 17 (4): 411–431. doi:10.1080/14623528.2015.1096583. ISSN 1462-3528. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Woolford, Andrew; Benvenuto, Jeff (October 2, 2015). "Canada and colonial genocide". Journal of Genocide Research. 17 (4): 373–390. doi:10.1080/14623528.2015.1096580. ISSN 1462-3528.

- 1 2 Dehaas, Josh (November 3, 2015). "'A new beginning' National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation opens in Winnipeg". CTVNews. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coulthard, Glen Sean (2014). Red skin, white masks : rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816679652.

- 1 2 Querengesser, Tim (December 2013). "Glen Coulthard & the three Rs". Northern Public Affairs. 2 (2): 59–61. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ↑ Rice, Brian; Snyder, Anna (2012). "Reconciliation in the Context of a Settler Society: Healing the Legacy of Colonialism in Canada". In DeGagné, Mike; Dewar, Jonathan; Lowry, Glen. "Speaking my truth" : reflections on reconciliation & residential school (PDF) (Scholastic Edition/First Printing. ed.). Aboriginal Healing Foundation. ISBN 9780988127425. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- 1 2 Garneau, David (2012). "Imaginary Spaces of Conciliation and Reconciliation" (PDF). West Coast Line. 46 (2). Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ↑ "What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation" (PDF). What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ↑ Tuck, Eve; Yang, K. Wayne (September 8, 2012). "Decolonization is not a metaphor". Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. 1 (1). ISSN 1929-8692.

- ↑ Rubenstein, Hymie; Rodney, Clifton (June 22, 2015). "Truth and Reconciliation report tells a 'skewed and partial story' of residential schools". National Post. Post Media. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ↑ Rubenstein, Hymie; Rodney, Clifton (June 4, 2015). "Debunking the half-truths and exaggerations in the Truth and Reconciliation report". National Post. Post Media. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ↑ Ballingall, Alex (April 6, 2017). "Lynn Beyak calls removal from Senate committee 'a threat to freedom of speech'". Toronto Star. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ↑ Galloway, Gloria (March 9, 2017). "Conservatives disavow Tory senator's positive views of residential schools". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on May 11, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- 1 2 Campion-Smith, Bruce (April 5, 2017). "Senator dumped from aboriginal issues committee for controversial views". Toronto Star. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ↑ Hiltz, Frank; MacDonald, Mark; Thompson, Michael (March 20, 2017). "There was nothing good: An open letter to Canadian Senator Lynn Beyak – Anglican Church of Canada". Anglican Church of Canada. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ↑ Hopper, Tristan (March 20, 2017). "'There was nothing good': Anglican church disputes Senator's claim that residential schools contained 'good'". National Post. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ↑ Roy, Gabrielle (August 29, 2018). "Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada launches after two years of input from communities". The Globe and Mail. The Canadian Press. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

External links

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada |