Tropical forest

Tropical forests are forested landscapes in tropical regions: i.e. land areas approximately bounded by the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, but possibly affected by other factors such as prevailing winds.

Categories of tropical forest types is difficult. While forests in temperate areas are readily categorised on the basis of tree canopy density, such schemes do not work well in tropical forests.[1] There is no single scheme that defines what a forest is, in tropical regions or elsewhere.[1][2] Because of these difficulties, information on the extent of tropical forests varies between sources. However Tropical Forests are extensive, making up just under half the world’s forests.[3]

Types of tropical forest

Tropical forests are often thought of as evergreen rainforests and moist forests, however in reality only up to 60% of tropical forest is rainforest[2] (depending on how this is defined - see maps). The remaining tropical forests are a diversity of many different forest types including: seasonally-dry tropical forest,[4] mangroves,[5] tropical freshwater swamp forests (or "flooded forests" such as the Várzea of the Amazon), dry forest,[6][7] open Eucalyptus forests,[8] tropical coniferous forests, savanna woodland (e.g. Sahelian forest) and montane forests[9] (the higher elevations of which are cloud forests). Over even relatively short distances, the boundaries between these biomes may be unclear, with ecotones between the main types.

The nature of tropical forest in any given area is affected by a number of factors, most importantly:

- Geographical: location and climatic zone (see sub-types), with:

- Precipitation levels and seasonality, with strong dry seasons significantly affecting flora (e.g. the predominance of lianas);[10]

- Temperature profile, which is relatively even in equatorial rainforest or with a cooler season towards subtropical latitudes;

- Elevation affects the above, often creating "ecological islands" with high endemism (e.g. Mount Kinabalu in the Borneo rainforest).[11]

- Historical: prehistoric age of forest and level of recent disturbance (see threats), changing primary (usually maximum biodiversity) into secondary forest, degenerating into bamboo forest after prolonged swidden agriculture (e.g. in several areas of Indo-China).[12]

- Soil characteristics (also subject to various classifications): including depth and drainage.[13]

The Global 200 scheme

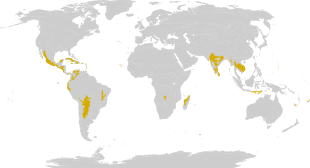

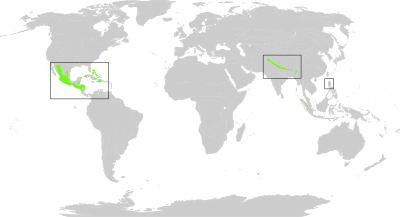

The Global 200 scheme, promoted by the World Wildlife Fund, classifies three main tropical forest habitat types (biomes), grouping together tropical and sub-tropical areas (maps below):

- Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests,

- Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests,

- Tropical and subtropical coniferous forests.

Extent of tropical and sub-tropical -

moist forest regions

moist forest regions dry forest regions

dry forest regions coniferous forest regions

coniferous forest regions

Threats

A number of tropical forests have been designated High-Biodiversity Wilderness Areas, but remain subject to a wide range of disturbances, both natural and anthropogenic. All tropical forests have experienced at least some levels of disturbance.[14]

A study in Borneo describes how, between 1973 and 2018, old-growth forest had been reduced from 76% to 50% of the island, mostly due to fire and agricultural expansion.[15] A widely-held view is that placing a value on the ecosystem services these forests provide may bring-about more sustainable policies. However, clear monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for environmental, social and economic outcomes are needed. For example, a study in Vietnam indicated that poor and inconsistent data combined with a lack of human resources and political interest (thus lack of financial support) are hampering efforts to improve forest land allocation and a Payments for Forest Environmental Services scheme.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 Francis E. Putz Kent H. Redford (2010) “The Importance of Defining ‘Forest’: Tropical Forest Degradation, Deforestation, Long-term Phase Shifts, and Further Transitions” BIOTROPICA 42(1): 10–20

- 1 2 Anatoly Shvidenko, Charles Victor Barber, Reidar Persson et al. 2005 "Millennium ecosystem assessment." Ecosystems and human wellbeing: a framework for assessment Washington, DC: Island Press

- ↑ D’Annunzio, Rémi, Lindquist, Erik J.,MacDicken, Kenneth G. 2017 “Global forest land-use change from 1990 to 2010: an update to a global remote sensing survey of forests Forest Resource Assessment Working Paper 187” FAO, Rome.

- ↑ Rodolfo Dirzo, Hilary S. Young, Harold A. Mooney and Gerado Ceballos (eds). 2011. “Seasonally Dry Tropical Forests: Ecology and Conservation.” Island Press, Washington, 2011.

- ↑ "Data" (PDF). www.botany.wisc.edu.

- ↑ Peter G. Murphy; Ariel E. Lugo 1986 “Ecology of Tropical Dry Forest” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, Vol. 17. (1986), pp. 67-88.

- ↑ "CIFOR publication survey" (PDF). Cifor.org. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- ↑ Woinarski, J. C. Z., Risler, J. and Kean, L. (2004), Response of vegetation and vertebrate fauna to 23 years of fire exclusion in a tropical Eucalyptus open forest, Northern Territory, Australia. Austral Ecology, 29: 156–176.

- ↑ Van Der Hammen T. (1991) Palaeoecological Background: Neotropics. In: Myers N. (eds) Tropical Forests and Climate. Springer, Dordrecht

- ↑ Chen YJ, Cao KF, Schnitzer SA, Fan ZX, Zhang JL, Bongers F (2015) Water-use advantage of lianas over trees in seasonal tropical forests. New Phytologist, 205[1]: 128–136

- ↑ Merckx VCFT, Hendriks KP, Beentjes KK, et al. (2015) Evolution of endemism on a young tropical mountain. Nature 524: 347–350

- ↑ Heinimann A, Peter Messerli P, Schmidt-Vogt D, Wiesmann U (2007) The Dynamics of Secondary Forest Landscapes in the Lower Mekong Basin: a Regional-scale Analysis. Mountain Research and Development 27(3): 232-241

- ↑ Schulte, A, Ruhiyat D (Eds.) (1998) Soils of Tropical Forest Ecosystems: Characteristics, Ecology and Management. Springer, 204 pp.

- ↑ Robin L. Chazdon 2003 “Tropical forest recovery: legacies of human impact and natural disturbances” Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 6/1,2, pp. 51–71

- ↑ Gaveau DLA (2016) What a difference 4 decades make: Deforestation in Borneo since 1973 CIFOR (retrieved 29 October 2017)

- ↑ Pham TT, Le ND, Vu TP, Nguyen HT, Nguyen VT (2016) Forest land allocation and payments for forest environmental services in four northwestern provinces of Vietnam: From policy to practice CIFOR (retrieved 29 October 2017)

External links