Trematode life cycle stages

Trematodes are any parasitic flatworm of the class Trematoda, especially a parasitic fluke. While consisting of two suckers, one being ventral and one being oral. They have a tegument covering which helps them with absorption and protection from the environment.

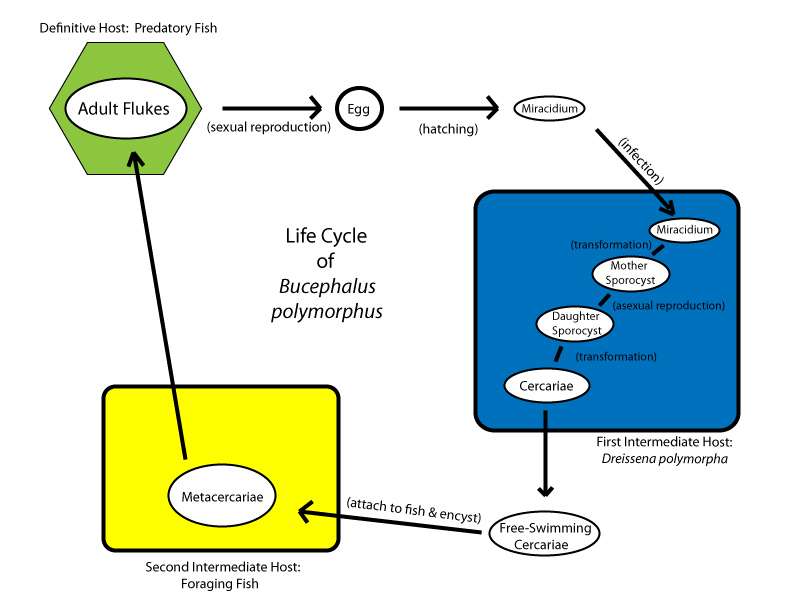

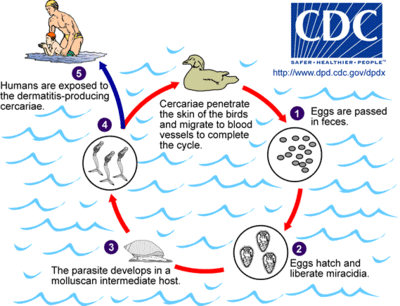

The life cycle of a typical trematode begins when the egg is immersed in water or from the adult worms in the definitive host. Some trematode eggs hatch in water, others are eaten by the first intermediate host and hatch within that host, so there are many different routes that a trematode could take to infect a host. Following this, the miracidium, which is free-swimming ciliated larva that a parasite moves from the egg to host stage, hatches which then also goes to find the mollusc host as the first intermediate host. This is where either a rediae or sporocyst will form depending on the host and if there is competition between the two. This eventually forms into a motile cercariae. The cercariae then either infects vertebrates through the skin of a host or is ingested and aims to locate the second intermediate host. When in the vertebrate host, the cercariae can then form into an adult, metacercariae or mesocercariae, depending on the life cycle, or is rejected through feces or urine. Then the metacercariae and second intermediate host has to be ingested by the definitive host for the life cycle to be completed.[1]

Typical life cycle stages

While the details vary with each species, the general life cycle stages are:

Egg

Found in either feces, sputum or in the urine. Depending on the species it will either be unembryonated (immature) or embryonated (ready to hatch), while all are operculated besides schistosomes. Some eggs are eaten by the host (snail) or hatch in the environment first when coming into contact with water.

Miracidium (plural miracidia)

These hatch from the eggs and switches to locate the host. They do not have a mouth therefore cannot eat and need to find the host quickly in order to survive because they have a limited amount of energy, which will then develop into the mother sporocyst. Its main function is to infect the first intermediate host, which can differ for different trematodes.[3]

Sporocyst

Elongated sac that produces either more sporocyst or rediae. This is where larva can be to develop.[4]

- Mother Sporocyst: They have loose plates (cilia) and migrate to gonas.

- Daughter Sporocyst: They are an asexual production of cercariae, they absorb nutrients while having no mouth.

Redia (plural rediae)

After the sporocyst form the larva, the first development from it forms the redia. [5] They have a mouth which allows them to have an advantage to their competitors because they can just consume them. Will either produce more rediae or start to form cercariae. The amount of rediae or daughter sporocyst varies a lot in the representatives of different deign taxa. [6]

Parasite Competition in Snail Hosts

Co-infections of different parasite species within the same post could occur and cause a competition between the rediae and sporocysts. Not all trematode species have a rediae stage, some may just have a sporocyst stage depending on the life cycle. The rediae are dominant to sporocyst because they have a "mouth" and are able to either eat their competitors' food or their competitor.

Cercaria (plural cercariae)

The larval form of the parasite, it develops within the germinal cells of the sporocyst or redia.[7] A cercaria has a tapering head with large penetration glands.[8] It may or may not have a long swimming "tail", depending on the species.[7] The motile cercaria finds and settles in a host where it will become either an adult, or a mesocercaria, or a metacercaria, according to species.

- Mesocercaria: They are involved in an encysted stage either on vegetation or in a host tissue on the second intermediate host. They have a hard shell and are also involved in the trophic transmission. This is where the parasite is able to infect the definitive host because it consumes the second intermediate host that has metacercariae on/in it.

- Metacercaria: A cercaria encysted and resting.They are only involved when there are 3 intermediate host life cycles.

Cercaria is also used as a genus of trematodes, when adult forms are not known.[9] The usage dates back to Müller, in 1773.[10]

Adult

The fully developed mature stage, it is capable of sexual reproduction.

Deviations from the typical life cycle

Not all trematodes follow the typical sequence of eggs, miracidia, sporocysts, rediae, cercariae, and adults. In some species, the redial stage is omitted, and sporocysts produce cercariae. In some species, the cercaria develops into an adult within the same host.

Many digenean trematodes require two hosts, one (typically a snail) where asexual reproduction occurs in sporocysts, the other a vertebrate (typically a fish) where the adult form engages in sexual reproduction to produce eggs. In some species (for example Ribeiroia) the cercaria encysts, and waits until the host is eaten by a third host, in whose gut it emerges and develops into an adult.

Most trematodes are hermaphroditic, but members of the family Schistosomatidae are dioecious. Males are shorter and stouter than the females.[8]

Representations of life cycles of several different trematode species

See also

References

- ↑ Poulin, Robert; Cribb, Thomas H (2002). "Trematode life cycles: Short is sweet?". Trends in Parasitology. 18 (4): 176–83. doi:10.1016/S1471-4922(02)02262-6. PMID 11998706.

- ↑ Caffara, Monica; Davidovich, Nadav; Falk, Rama; Smirnov, Margarita; Ofek, Tamir; Cummings, David; Gustinelli, Andrea; Fioravanti, Maria L (2014). "Redescription of Clinostomum phalacrocoracis metacercariae (Digenea: Clinostomidae) in cichlids from Lake Kinneret, Israel". Parasite. 21: 32. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014034. PMC 4078730. PMID 24986336.

- ↑ Galaktionov, K. V., & Dobrovolʹskiĭ, A. A. (2003). The biology and evolution of trematodes: An essay on the biology, morphology, life cycles, transmission, and evolution of digenetic trematodes. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- ↑ Fried, Bernard, and Thaddeus K. Graczyk. Echinostomes as Experimental Models for Biological Research. Springer, 2011.

- ↑ Fried, Bernard, and Thaddeus K. Graczyk. Echinostomes as Experimental Models for Biological Research. Springer, 2011.

- ↑ Galaktionov, K. V., & Dobrovolʹskiĭ, A. A. (2003). The biology and evolution of trematodes: An essay on the biology, morphology, life cycles, transmission, and evolution of digenetic trematodes. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- 1 2 "Glossary". VPTH 603 Veterinary Parasitology. University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

- 1 2 "Schistosoma". Australian Society for Parasitology. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Cercaria at WoRMS

- ↑ Vermium terrestrium et fluviatilium seu animalium infusoriorum, helminthicorum et testaceorum, non marinorum, succincta historia. OF Müller, 1773