Tlaltecuhtli

Tlaltecuhtli [tlal-teh-COO-tlee] is a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican deity worshipped primarily by the Mexica (Aztec) people. Sometimes referred to as the "earth monster," Tlaltecuhtli's dismembered body was the basis for the world in the Aztec creation story of the fifth and final cosmos.[1] In carvings, Tlaltecuhtli is often depicted as an anthropomorphic being with splayed arms and legs. Considered the source of all living things, she had to be kept sated by human sacrifices which would ensure the continued order of the world.

Tlaltecuhtli is known from several post-conquest manuscripts that surveyed Mexica mythology and belief systems, such as the Histoyre du méchique[2], Florentine Codex, and Codex Bodley, both compiled in the sixteenth century.[3]

Representations in Art

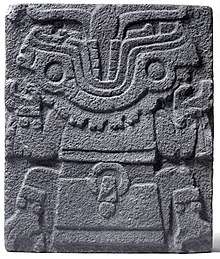

Tlaltecuhtli is typically depicted as a squatting toad-like creature with massive claws, a gaping mouth, and crocodile skin, which represented the surface of the earth. In carvings, her mouth is often shown with a river of blood flowing from it or a flint knife between her teeth, a reference to the human blood she thirsted for. Her elbows and knees are often adorned with human skulls, and she sometimes appears with multiple mouths full of sharp teeth all over her body. In some images, she wears a skirt made of human bones and a star border, a symbol of her primordial sacrifice.[4]

Many sculptures of Tlaltecuhtli were meant only for the gods and were not intended to be seen by humans. She was often carved onto the bottom of sculptures where they made contact with the earth, or on the undersides of stone boxes called cuauhxicalli ("eagle box"), which held the sacrificial hearts she was so partial to. In reference to her mythological function as the support of the earth, Tlaltecuhtli was sometimes carved onto the cornerstones of temples, such as the pyramid platform at El Tajin.[5]

Tlaltecuhtli's importance in the Mexica pantheon is demonstrated by her inclusion in major works of art. A representation of the goddess can be found on each side of the 1503 CE Coronation Stone of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II, alongside the glyphs for fire and water — traditional symbols of war. Historian Mary Miller even suggests that Tlaltecuhtli may be the face in the center of the famous Aztec Calendar Stone (Piedra del Sol), where she symbolizes the end of the 5th and final Aztec cosmos.[4]

Tlaltecuhtli appears in the Aztec calendar as the 2nd of the 13 deity days, and her date glyph is 1 Rabbit.

Creation Narrative

According to the Bodley Codex,[6] there were several earth gods: Tlaltecuhtli, Coatlique, Cihuacoatl and Tlazolteotl. Tlaltecuhtli was especially important because her body represented the earth that humans lived on.

In the Mexica creation story, Tlatlecuhtli is described as a sea monster (sometimes called Cipactli) who dwelled in the ocean after the fourth Great Flood. She was an embodiment of the chaos that raged before creation.[4] One day, the gods Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca descended from the heavens in the form of serpents and found the monstrous Tlaltecuhtli sitting on top of the ocean with giant fangs, crocodile skin, and gnashing teeth calling for flesh to feast on. The two gods decided that the fifth cosmos could not prosper with such a horrible creature roaming the world, and so they set out to destroy her. To attract her, Tezcatlipoca used his foot as bait, and Tlatlecuhtli ate it. In the fight that followed, Tezcatlipoca lost his foot and Tlaltecuhtli lost her lower jaw, taking away her ability to sink below the surface of the water. After a long struggle, Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl managed to rip her body in two — from the upper half came the sky, and from the lower came the earth.[7] She remained alive, however, and demanded human blood as repayment for her sacrifice.

The other gods were angered to hear of Tlatlecuhtli's treatment and decreed that the various parts of her dismembered body would become the features of the new world. Her skin became grasses and small flowers, her hair the trees and herbs, her eyes the springs and wells, her nose the hills and valleys, her shoulders the mountains, and her mouth the caves and rivers.[2]

Rites and Rituals

Since Tlatlecuhtli's body was transformed into the geographical features, the Mexica attributed strange sounds from the earth as either the screams of Tlaltecuhtli in her dismembered agony, or her calls for human blood to feed her. As a source of life, it was thought necessary to appease Tlaltecuhtli with blood sacrifices, especially human hearts. The Aztecs believed that Tlatlecuhtli's insatiable appetite had to be satisfied or the goddess would cease her nourishment of the earth and crops would fail.[2]

The Mexica believe Tlaltecuhtli to swallow the sun between her massive jaws at dusk, and regurgitate it the next morning at dawn. The fear that this cycle could be interrupted, like during solar eclipses, was often the cause of uneasiness and increased ritual sacrifice.[8] Tlaltecuhtli's connection to the sun ensured that she was included in the prayers offered to Tezcatlipoca before Aztec military campaigns.[8]

Finally, because of Tlatlecuhtli's association with fertility, midwives called on her aid during difficult births—when an "infant warrior" threatened to kill the mother during labor.[4]

Gender Debate

One of the largest modern debates surrounding Tlaltecuhtli is over the deity's gender. In Nahuatl, "tlal-" translates to "earth," and "tecuhtli" to "lord." Though this word is masculine, there are notable exceptions—for example, the goddesses Ilamatecuhtli and Chalmecatecuhtli.[9] While Tlaltecuhtli's name is masculine, the deity is most often depicted with female characteristics and clothing. According to Miller, "Tlaltecuhtli literally means 'Earth Lord,' but most Aztec representations clearly depict this creature as female, and despite the male gender of the name, some sources call Tlaltecuhtli a goddess. [She is] usually in a hocker, or birth-giving squat, with head flung backwards and her mouth of flint blades open."[4]

Other scholars, like Alphonso Caso, interpret this pose as a male Tlaltecuhtli crouching under the earth with his mouth wide open, waiting to devour the dead.[10] While one mostly encounters Tlaltecuhtli as female, some depictions are clearly male (though these distinctions may at times arise from the Spanish-language gendering process).[11] H.B. Nicholson writes, "most of the available evidence suggests that... the earth monster in the mamazouhticac position was conceived to be female and depicted wearing the costume proper to that sex. A male aspect of that deity was also recognized and occasionally represented in appropriate garb—but was apparently quite subordinate to the more fundamental and pervasive female conception."[12]

This ambiguity has prompted some scholars to argue that Tlaltecuhtli may have possessed a dual gender like several other Mesoamerican primordial deities. In Bernardino Sahagún's Florentine Codex, for example, Tlaltecuhtli is invoked as in tonan in tota —"our mother, our father"—and the deity is described as both a god and a goddess.[13] Rather than signal hermaphroditism or androgyny, archaeologist Leonardo Lopez Lujan suggests that these varying embodiments are a testament to the deity's importance in the Mexica pantheon.[9]

Monolith

In 2006, a massive monolith of Tlaltecuhtli was discovered in an excavation at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City).[14] The sculpture measures approximately 13.1 x 11.8 feet (4 x 3.6 meters) and weighs nearly 12 tons, making it one of the largest Aztec monoliths ever discovered—larger even than the Calendar Stone. The sculpture, carved in a block of pink andesite, presents the goddess in her typical squatting position and is vividly painted in red, white, black, and blue. The stone was broken into four pieces by the weight of a colonial building that once sat above it. Reassembled, one can see Tlaltecuhtli's skull and bones dress and the river of blood flowing from her mouth.

Though most renderings of Tlaltecuhtli were placed face down, this monolith was found face up, indicating that it may have been a tombstone used to mark a royal burial. Clutched in her lower right claw is the year glyph for 10 rabbit (1502 CE). Lopez Lujan noted that according to the surviving codices, 1502 was the year that one of the empire's most feared rulers, Ahuitzotl, was laid to rest.[7] Known for their reverence, the detail and scale of the carving would be in keeping with Aztec traditions to honor their monarchs.

After several years of excavation and restoration, the monolith can be seen on display at the the Museum of the Templo Mayor in Mexico City.

References

- ↑ "Tlaltecuhtli". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- 1 2 3 de Jonghe, Edouard (1557). Histoyre du méchique.

- ↑ "Codex Bodley". c. 1500.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Miller, Mary Ellen and Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames and Hudson.

- ↑ "Mother Earth for the Aztecs Was a Horrific, Demanding Monster". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ↑ Caso, Alphonso (fifth printing 1978) The Aztecs: People of the Sun Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0414-7 pp. 52-56 OCLC 58-11603

- 1 2 Lopez Lujan, Leondardo (2010). Tlaltecuhtli. Mexico City: Sextil Editores.

- 1 2 de Sahagún, Bernardino (1590). Florentine Codex, Book 6.

- 1 2 Lopez Lujan, Leonardo (2010). Tlaltecuhtli. Mexico City: Sextil Editores. p. 101.

- ↑ Caso, Alphonso (fifth printing 1978) The Aztecs: People of the Sun Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0414-7 pp. 52-56 OCLC 58-11603

- ↑ Henderson, Lucia (2007). Producer of the Living, Eater of the Dead: Revealing Tlaltecuhtli, the Two-Faced Aztec Earth. Archaeopress. p. 5.

- ↑ Nicholson, H.B. (1967). "A Fragment of an Aztec Relief Carving of the Earth Monster". Journal de la Société des Americanistes. 56: 81.

- ↑ de Sahagún, Bernardino (1590). Florentine Codex, Book 6. p. 13.

- ↑ "El monolito de las Ajaracas es de Tlatecuhtli", La Jornada, November 17, 2006. (in Spanish)