Tiwanaku empire

| Tiwanaku state

Tiahuanaco | |

|---|---|

| 550–1000 | |

Middle Horizon | |

| Capital | Tiwanaku, Bolivia |

| Common languages | Puquina[1] |

| Historical era | Pre-Columbian |

• Established | 550 |

• Disestablished | 1000 |

| Today part of |

|

The Tiwanaku state (Spanish: Tiahuanaco or Tiahuanacu) was a Pre-Columbian polity in western Bolivia based in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. Tiwanaku was one of the most significant Andean civilizations. Its influence extended into present-day Peru and Chile and lasted from around AD 550 to 1000. Its capital was the monumental city of Tiwanaku, located at the center of the state's core area in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. This area has clear evidence for large-scale agricultural production on raised fields that probably supported the urban population of the capital. Researchers debate whether these fields was administered by a bureaucratic state (top-down) or through collaboration of a segmented state or federation with local autonomy (bottom-up; see review of debate in Janusek 2004:57-73)[2]. One obsolete theory suggests that Tiwanaku was an expansive military empire, based on comparisons to the later Inca Empire, but supporting evidence is weak.

Tiwanaku was a multi-cultural "hospitality state"[3] that brought people together to build large monuments, perhaps as part of large religious festivals. This may have been the central dynamic that attracted people from hundreds of kilometers away, who may have traveled there as part of llama caravans to trade, make offerings, and honor the gods. Tiwanaku grew into the Andes' most important pilgrimage destination and one of the continent's largest Pre-Columbian cities, reaching a population of 10,000 to 20,000 around AD 800[2].

Outside of the state's core area in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin, there were Tiwanaku colonies on the coast of Peru, where highland people imitated Tiwanaku temples and ceramics, and cemeteries in northern Chile with elaborate grave goods in the Tiwanaku style. Despite the clear connections to these enclaves, there is little evidence that the state controlled the territory or people in between, that is, its territory was not contiguous. With a few important exceptions, the state's influence outside the Lake Titicaca Basin was "soft power" that blossomed into a powerful, wide-spread, and enduring cultural hegemony.

Rise

The site of Tiwanaku was founded around AD 110 during the Late Formative Period, when there were a number of growing settlements in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. Between AD 450 and 550, other large settlements were abandoned, leaving Tiwanaku as the pre-eminent center in the region. Beginning around AD 600 its population exploded, probably due to a massive immigration from the surrounding countryside, and large parts of the city were built or remodeled[2]. New and larger carved monoliths were erected, temples were built, and a standardized polychrome pottery style was produced on a massive scale.[4]

Tiwanaku's influence, most clearly documented by the presence of its decorated ceramics, expanded into the Yungas and influenced many other cultures in Peru, Bolivia, and northern Argentina and Chile. Some statues at Tiwanaku were taken from other regions, where the stones were placed in a subordinate position to the Gods of the Tiwanaku. They displayed the power that their state had over others.[5] Archaeologists have documented Tiwanaku ceramics at a large number of sites in and beyond the Lake Titicaca Basin, attesting to the expansive influence of Tiwanaku symbols and attached messages of power.

The population grew rapidly between 600 and 800, becoming an important regional power in the southern Andes. William H. Isbell states that "Tiahuanaco underwent a dramatic transformation between 600 and 700 that established new monumental standards for civic architecture and greatly increased the resident population."[6] Early estimates suggested the city covered approximately 6.5 square kilometers at with 15,000 to 30,000 inhabitants.[7] More recent surveys estimate the site's maximum size between 3.8 and 4.2 square kilometers and a population of 10,000 to 20,000.[2]

In the rest of the southern Lake Titicaca Basin, hundreds of smaller settlements have been found. Some of the largest and most important were Lukurmata, Qeya Kuntu, Kirawi, Waka Kala, Sonaji, Kala Uyuni, and Khonko Wankane.[2]

Colonies and Diaspora

Archaeologists such as Paul Goldstein have showed that the Tiwanaku diaspora expanded outside of the altiplano area and into the Moquegua Valley in Peru. After AD 750, there is growing Tiwanaku presence at the Chen Chen site and the Omo site complex, where a ceremonial center was built. Excavations at Omo settlements show signs of similar architecture characteristic of Tiwanaku, such as a temple and terraced mound.[8] Evidence of similar types of artificial cranial deformation in burials between the Omo site and the main site of Tiwanaku is also being used for this argument.[9]

Tiwanaku established several colonies as far as 300 km away. One of the better researched is the colony in Moquegua Valley in Peru, which is 150 km from lake Titicaca and flourished between 400 and 1100. This colony was an agricultural and mining center, producing copper and silver.[10] Small colonies were also established in Chile’s Azapa Valley.

Agriculture

Tiwanaku's location between the lake and dry highlands provided key resources of fish, wild birds, plants, and herding grounds for camelids, particularly llamas.[11] Tiwanaku's economy was based on exploiting the resources of the lake Titicaca, herding of llamas and alpacas and organized farming in raised field systems. Llama meat was consumed and potatoes, quinoa, beans and maize grown. Storage of food was important in the uncertain high altitude climate, so technologies for freeze-dried potatoes and sun-dried meat were developed.[2]

The Titicaca Basin is the most productive environment in the area, with predictable and abundant rainfall. The Tiwanaku culture developed expanded farming. To the east, the Altiplano is an area of very dry arid land.[7] The Tiwanaku developed a distinctive farming technique known as "flooded-raised field" agriculture (suka qullu). Such fields were used widely in regional agriculture, together with irrigated fields, pasture, terraced fields and artificial ponds.[7] Water from Katari and Tiwanku rivers was used to water raised fields, that covered up to 130 square km.

Artificially raised planting mounds were separated by shallow canals filled with water. The canals supply moisture for growing crops, but they also absorb heat from solar radiation during the day. This heat is gradually emitted during the bitterly cold nights and provided thermal insulation against the endemic frost in the region. Traces of similar landscape management have been found in the Llanos de Moxos region (Amazonian flood plains of the Moxos).[12] Over time, the canals also were used to farm edible fish. The resulting canal sludge was dredged for fertilizer.

Though labor-intensive, a suka qullu produces impressive yields. While traditional agriculture in the region typically yields 2.4 metric tons of potatoes per hectare, and modern agriculture (with artificial fertilizers and pesticides) yields about 14.5 metric tons per hectare, suka qullu agriculture yields an average of 21 tons per hectare.[7] Modern agricultural researchers have re-introduced the technique of suka qullu. Significantly, the experimental suka qullu fields recreated in the 1980s by University of Chicago´s Alan Kolata and Oswaldo Rivera suffered only a 10% decrease in production following a 1988 freeze that killed 70-90% of the rest of the region's production.[13] Development by the Tiwanaku of this kind of protection against killing frosts in an agrarian civilization was invaluable to their growth.[13]

As the population grew, occupational niches developed, and people began to specialize in certain skills. There was an increase in artisans, who worked in pottery, jewelry and textiles. Like the later Incas, the Tiwanaku had few commercial or market institutions. Instead, the culture relied on elite redistribution.[14] In this view of Tiwanaku as a bureaucratic state, elites controlled the economic output, but were expected to provide each commoner with all the resources needed to perform his or her function. Selected occupations include agriculturists, herders, pastoralists, etc. Such separation of occupations was accompanied by hierarchichal stratification.[15] The elites gained their status by control of the surplus of food obtained from all regions, which they then redistributed among all the people. Control of llama herds became very significant to Tiwanaku. The animals were essential for transporting staple and prestige goods.

Explosive Collapse

Suddenly around AD 1000, Tiwanaku ceramics stopped being produced as the state's largest colony (Moquegua) and the urban core of the capital were abandoned within a few decades.[16] The end date for the Tiwanaku state is sometimes extended to AD 1150, but this only considers raised fields, not urban occupation or ceramic production. One proposed explanation is that a severe drought rendered the raised-field systems ineffective, food surplus dropped, and with it, elite power, leading to state collapse.[7] However, this narrative has been challenged[17], in part because of more refined cultural and climate chronologies, which now suggest that the drought did not start until AD 1020 or 1040, shortly after the state's explosive collapse.[16][18]

This lends greater support to alternative theories of collapse that suggest social dynamics within the Tiwanaku state led to its demise. Some areas of the capital show signs of intentional destruction, though this could have taken place at any time. Monolithic gates, like Gateway of the Sun, were tipped over and broken.[10] By the end of Tiwanaku V period the Putuni complex was burned and food storage jars smashed. This indicates an event of destruction, followed by abandonment of the site. Colonies in Moquegua and on Isla del Sol were also abandoned around this time.[19]

Religion

What is known of Tiwanaku religious beliefs is based on archaeological interpretation and some myths, which may have been passed down to the Incas and the Spanish. They seem to have worshipped many gods, perhaps centered on agriculture. One of the most important gods was one that would eventually develop into the Incan God Viracocha, the god of action, shaper of many worlds, and destroyer of many worlds. He created people, with two servants, on a great piece of rock. Then he drew sections on the rock and sent his servants to name the tribes in those areas.

In Tiwanaku, he created the people out of rock and brought life to them through the earth. The Tiwanaku believed that Viracocha created giants to move the massive stones that comprise much of their archaeology, but then grew unhappy with the giants and created a flood to destroy them.

Viracocha is carved into the noted Gateway of the Sun, to overlook his people and lands. The Gateway of the Sun is a monolithic structure of regular, non-monumental size. Its dimensions suggest that other regularly sized buildings existed at the site. It was found at Kalasasaya, but due to the similarity of other gateways found at Pumapunku, it is thought to have been originally part of a series of doorways there.[7] It is recognized for its singular, great frieze. This is thought to represent a main deity figure surrounded by either calendar signs or natural forces for agricultural worship. Along with Viracocha, another statue is in the Gateway of the Sun. This statue is believed to be associated with the weather:

a celestial high god that personified various elements of natural forces intimately associated the productive potential of altiplano ecology: the sun, wind, rain, hail – in brief, a personification of atmospherics that most directly affect agricultural production in either a positive or negative manner[7]

It has twelve faces covered by a solar mask, and at the base thirty running or kneeling figures.[7] Some scientists believe that this statue is a representation of the calendar with twelve months and thirty days in each month.[7]

Other evidence points to a system of ancestor worship at Tiwanaku. The preservation, use, and reconfiguration of mummy bundles and skeletal remains, as with the later Inca, may suggest that this is the case.[7] Later cultures within the area made use of large "above ground burial chambers for the social elite... known as "chullpas".[7] Similar, though smaller, structures were found within the site of Tiwanaku.[7]

Kolata suggests that, like the later Inca, the inhabitants of Tiwanaku may have practiced similar rituals and rites in relation to the dead. The Akapana East Building has evidence of ancestor burial. The human remains at Akapana East seem to be less for show and more for proper burial. The skeletons show many cut marks that were most likely made by defleshing or excarnation after death. The remains were then bundled up and buried rather than left out in the open.[5]

The Tiwanaku conducted human sacrifices on top of a building known as the Akapana. People were disemboweled and torn apart shortly after death and laid out for all to see. It is speculated that this ritual was a form of dedication to the gods. The type of human sacrifice included victims being hacked in pieces, dismembered, exposed to the elements and carnivores before being deposed in trash.[19] Research showed that one man who was sacrificed was not a native to the Titicaca Basin, leaving room to think that sacrifices were most likely of people originally from other societies.[7]

Architecture and art

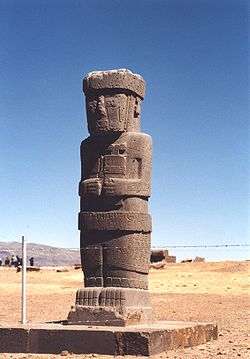

Tiwanaku monumental architecture is characterized by large stones of exceptional workmanship. In contrast to the masonry style of the later Inca, Tiwanaku stone architecture usually employs rectangular ashlar blocks laid in regular courses. Their monumental structures were frequently fitted with elaborate drainage systems. The drainage systems of the Akapana and Pumapunku structures include conduits composed of red sandstone blocks held together by ternary (copper/arsenic/nickel) bronze architectural cramps. The I-shaped architectural cramps of the Akapana were created by cold hammering of ingots. In contrast, the cramps of the Pumapunku were created by pouring molten metal into I-shaped sockets.[20] The blocks have flat faces that do not need to be fitted upon placement because the grooves make it possible for the blocks to be shifted by ropes into place. The main architectural appeal of the site comes from the carved images and designs on some of these blocks, carved doorways, and giant stone monoliths.[21]

The quarries that supplied the stone blocks for Tiwanaku lie at significant distances from this site. The red sandstone used in this site's structures has been determined by petrographic analysis to come from a quarry 10 kilometers away—a remarkable distance considering that the largest of these stones weighs 131 metric tons.[22] The green andesite stones that were used to create the most elaborate carvings and monoliths originate from the Copacabana peninsula, located across Lake Titicaca.[22] One theory is that these giant andesite stones, which weigh over 40 tons, were transported some 90 kilometers across Lake Titicaca on reed boats, then laboriously dragged another 10 kilometers to the city.[23]

Lukurmata

Lukurmata, located in the Katari valley was the second great city of the Tiwanaku state. Between 600 and 800 it expanded from 20 hectares to 120 hectares.[19] First established nearly two thousand years ago, it grew to be a major ceremonial center in the Tiwanaku state, a polity that dominated the south-central Andes from 400 to 1200. After the Tiwanaku state collapsed, Lukurmata rapidly declined, becoming once again a small village. The site shows evidence of extensive occupation that antedates the Tiwanakan civilization.

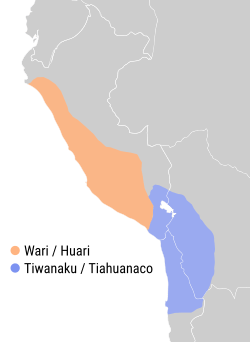

Relationship with Wari

The Tiwanaku shared domination of the Middle Horizon with the Wari culture (based primarily in central and south Peru) although found to have built important sites in the north as well (Cerro Papato ruins). Their culture rose and fell around the same time; it was centered 500 miles north in the southern highlands of Peru. The relationship between the two polities is unknown. Definite interaction between the two is proved by their shared iconography in art. Significant elements of both of these styles (the split eye, trophy heads, and staff-bearing profile figures, for example) seem to have been derived from that of the earlier Pukara culture in the northern Titicaca Basin.

The Tiwanaku created a powerful ideology, using previous Andean icons that were widespread throughout their sphere of influence. They used extensive trade routes and shamanistic art. Tiwanaku art consisted of legible, outlined figures depicted in curvilinear style with a naturalistic manner, while Wari art used the same symbols in a more abstract, rectilinear style with a militaristic style.[24]

Tiwanaku sculpture is comprised typically of blocky, column-like figures with huge, flat square eyes, and detailed with shallow relief carving. They are often holding ritual objects, such as the Ponce Stela or the Bennett Monolith. Some have been found holding severed heads, such as the figure on the Akapana, who possibly represents a puma-shaman. These images suggest the culture practiced ritual human beheading. As additional evidence, headless skeletons have been found under the Akapana.

They also used ceramics and textiles, composed of bright colors and stepped patterns. An important ceramic artifact is the qiru, a drinking cup that was ritually smashed after ceremonies and placed with other goods in burials. Over time, the style of ceramics changed. The earliest ceramics were "coarsely polished, deeply incised brownware and a burnished polychrome incised ware". Later the Qeya style became popular during the Tiwanaku III phase, "Typified by vessels of a soft, light brown ceramic paste". These ceramics included libation bowls and bulbous-bottom vases.[25]

Examples of textiles are tapestries and tunics. The objects typically depicted herders, effigies, trophy heads, sacrificial victims, and felines. Such small, portable objects of ritual religious meaning were a key to spreading religion and influence from the main site to the satellite centers. They were created in wood, engraved bone, and cloth. They depicted puma and jaguar effigies, incense burners, carved wooden hallucinogenic snuff tablets, and human portrait vessels. Like the Moche, Tiwanaku portraits expressed individual characteristics.[26]

References

- ↑ Heggarty, P; Beresford-Jones, D (2013). "Andes: linguistic history". In Ness, I; P, Bellwood. The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 401–9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Janusek, John (2004). Identity and Power in the Ancient Andes: Tiwanaku Cities through Time. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415946346.

- ↑ Bandy, Matthew (2013). "Tiwanaku Origins and Early Development: The Political and Moral Economy of a Hospitality State". In Vranich, Alexei; Stanish, Charles. Visions of Tiwanaku. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. pp. 135–150. ISBN 978-0-917956-09-6.

- ↑ Stanish, Charles (2003). Ancient Titicaca: The Evolution of Complex Society in Southern Peru and Northern Bolivia. University of California Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-520-23245-7.

- 1 2 Blom, Deborah E. and John W. Janusek. "Making Place: Humans as Dedications in Tiwanaku", World Archaeology (2004): 123–41.

- ↑ Isbell, William H. 'Wari and Tiwanaku: International Identities in the Central Andean Middle Horizon'. 731-751.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Kolata, Alan L. (December 11, 1993). The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean Civilization. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-55786-183-2.

- ↑ Goldstein, Paul (1993). Tiwanaku Temples and State Expansion: A Tiwanaku Sunken-Court Temple in Moquegua, Peru.

- ↑ Hoshower, Lisa M. (1995). Artificial Cranial Deformation at the Omo M10 Site: A Tiwanaku Complex from the Moquegua Valley, Peru.

- 1 2 Experience on the Frontier: A Tiwanaku Colony's Shifts Over Time

- ↑ Bruhns, K (1994), Ancient South America, Cambridge University Press , 424 pp.

- ↑ Kolata, Alan L (1986), "The Agricultural Foundations of the Tiwanaku State: A View from the Heartland", American Antiquity, 51: 748–62, doi:10.2307/280863 .

- 1 2 Kolata, Alan L. Valley of the Spirits: A Journey into the Lost Realm of the Aymara, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 1996.

- ↑ Smith, Michael E. (2004), "The Archaeology of Ancient Economies," Annu. Rev. Anthrop. 33: 73-102.

- ↑ Bahn, Paul G. Lost Cities. New York: Welcome Rain, 1999.

- 1 2 Owen, Bruce. "Distant Colonies and Explosive Collapse: The Two Stages of the Tiwanaku Diaspora in the Osmore Drainage". Latin American Antiquity. 16: 45–81. doi:10.2307/30042486.

- ↑ Calaway, Michael (2005). "Ice-cores, Sediments and Civilisation Collapse: A Cautionary Tale from Lake Titicaca". Antiquity. 79: 778–790.

- ↑ Lechleitner, Franziska; et al. "Tropical rainfall over the last two millennia: evidence for a low-latitude hydrologic seesaw". Nature. doi:10.1038/srep45809.

- 1 2 3 The Role of Silver Ore Reduction in Tiwanaku State Expansion Into Puno Bay, Peru

- ↑ Lechtman, Heather N., MacFarlane, and Andrew W., 2005, "La metalurgia del bronce en los Andes Sur Centrales: Tiwanaku y San Pedro de Atacama". Estudios Atacameños, vol. 30, pp. 7-27.

- ↑ Isbell, W. H., 2004, Palaces and Politics in the Andean Middle Horizon. in S. T. Evans and J. Pillsbury, eds., pp. 191-246. Palaces of the Ancient New World. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C.

- 1 2 Ponce Sanginés, C. and G. M. Terrazas, 1970, Acerca De La Procedencia Del Material Lítico De Los Monumentos De Tiwanaku. Publication no. 21. Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia.

- ↑ Harmon, P., 2002, "Experimental Archaeology, Interactive Dig, Archaeology Magazine, "Online Excavations" web page, Archaeology magazine.

- ↑ Stone-Miller, Rebecca (2002) [1995]. Art of the Andes: from Chavin to Inca.

- ↑ Bray, Tamara L. The Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires, New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2003

- ↑ Rodman, Amy Oakland (1992). Textiles and Ethnicity: Tiwanaku in San Pedro de Atacama.

Bibliography

- Bermann, Marc Lukurmata Princeton University Press (1994) ISBN 978-0-691-03359-4.

- Bruhns, Karen Olsen, Ancient South America, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, c. 1994.

- Goldstein, Paul, "Tiwanaku Temples and State Expansion: A Tiwanaku Sunken-Court Temple in Moduegua, Peru", Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 4, No. 1 (March 1993), pp. 22–47, Society for American Archaeology.

- Hoshower, Lisa M., Jane E. Buikstra, Paul S. Goldstein, and Ann D. Webster, "Artificial Cranial Deformation at the Omo M10 Site: A Tiwanaku Complex from the Moquegua Valley, Peru", Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 6, No. 2 (June, 1995) pp. 145–64, Society for American Archaeology.

- Kolata, Alan L., "The Agricultural Foundations of the Tiwanaku State: A View from the Heartland", American Antiquity, Vol. 51, No. 4 (October 1986), pp. 748–762, Society for American Archaeology.

- Kolata, Alan L (June 1991), "The Technology and Organization of Agricultural Production in the Tiwanaku State", Latin American Antiquity, Society for American Archaeology, 2 (2): 99–125, doi:10.2307/972273 .

- Protzen, Jean-Pierre and Stella E. Nair, "On Reconstructing Tiwanaku Architecture", The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 59, No. 3 (September 2000), pp. 358–71, Society of Architectural Historians.

- Reinhard, Johan, "Chavin and Tiahuanaco: A New Look at Two Andean Ceremonial Centers." National Geographic Research 1(3): 395–422, 1985.

- ——— (1990), "Tiahuanaco, Sacred Center of the Andes", in McFarren, Peter, An Insider's Guide to Bolivia, La Paz, pp. 151–81 .

- ——— (1992), "Tiwanaku: Ensayo sobre su cosmovisión" [Tiwanaku: essay on its cosmovision], Revista Pumapunku (in Spanish), 2: 8–66 .

- Stone-Miller, Rebecca (2002) [c. 1995], Art of the Andes: from Chavin to Inca, London: Thames & Hudson .