Thutmose (sculptor)

| Thutmose | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14th century BC |

| Nationality | Egyptian |

| Known for | Sculpture |

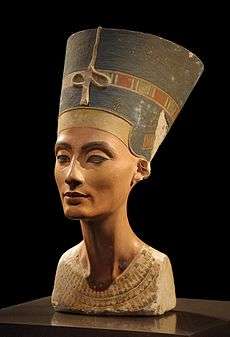

| Notable work | Bust of Nefertiti |

| Movement | Amarna art |

| Patron(s) | Pharaoh Akhenaten |

"The King's Favourite and Master of Works, the Sculptor Thutmose" (also spelled Djhutmose, Thutmosis, and Thutmes), flourished 1350 BC, is thought to have been the official court sculptor of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten in the latter part of his reign. A German archaeological expedition digging in Akhenaten's deserted city of Akhetaton, at Amarna, found a ruined house and studio complex (labeled P47.1-3)[1] in early December 1912;[2] the building was identified as that of Thutmose based on an ivory horse blinker found in a rubbish pit in the courtyard inscribed with his name and job title.[3] Since it gave his occupation as "sculptor" and the building was clearly a sculpture workshop, the determination seemed logical and has proven to be accurate.

Recovered works

Among many other sculptural items recovered at the same time was the polychrome bust of Nefertiti, apparently a master study for others to copy, which was found on the floor of a storeroom. In addition to this now-famous bust, twenty-two plaster casts of faces—some of which are full heads, others just the face—were found in Rooms 18 and 19 of the studio, with an additional one found in Room 14.[4] Eight of these have been identified as various members of the royal family, including Akhenaten, his other wife Kiya, his late father Amenhotep III, and his eventual successor Ay. The rest represent unknown individuals, presumably contemporary residents of Amarna.[4]

A couple of the pieces found in the workshop depict realistic images of older noblewomen, something rare in Ancient Egyptian art, which more often portrayed women in an idealized manner as always young, slender, and beautiful.[5] One of the plaster faces depicts an older woman, with wrinkles at the corner of her eyes, bags under them, and a deeply lined forehead. This piece has been described as showing "a greater variety of wrinkles than any other depiction of an elite woman from ancient Egypt"[6] It is thought to represent the image of a wise, older woman.[6] A small statue of an aging Nefertiti also was found in the workshop, depicting her with a rounded, drooping belly, thick thighs, and a curved line at the base of her abdomen showing that she had borne several children, perhaps intended to project an image of fertility.[7]

Examples of his work recovered from his abandoned studio may be viewed at the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin, the Cairo Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Upon the death of Akhenaten, the seat of government was returned from Amarna to Thebes and the associated bureaucratic and professional industries followed.

Tomb

In 1996 the French Egyptologist Alain Zivie discovered at Saqqara the decorated rock cut tomb of the "head of the painters in the place of truth", Thutmose. The tomb dates to the time shortly after the Amarna Period. Although the title of the Thutmose in Saqqara is slightly different from the title of the Thutmose known from Amarna, it seems likely that they refer to the same person and that the different titles represent different stages in his career.[8]

An extensive article by Zivie in the July-August 2018 edition of Biblical Archaeology Review provides great detail and many images of artifacts recovered in an adjacent tomb,[9] discussion of many aspects of several topics regarding Ancient Egyptian research and identification, as well as information about the sculptor, Thutmose.

Gallery of images

Plaster face of an older Amarna-era woman, from late in Akhenaten's reign, years 14-17, from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose, on display at the Ägyptisches Museum

Plaster face of an older Amarna-era woman, from late in Akhenaten's reign, years 14-17, from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose, on display at the Ägyptisches Museum Plaster face of a young Amarna-era woman, (thought by many to represent Kiya, one of Akhenaten's wives), from late in Akhenaten's reign, years 14-17, from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Plaster face of a young Amarna-era woman, (thought by many to represent Kiya, one of Akhenaten's wives), from late in Akhenaten's reign, years 14-17, from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City Portrait study thought to represent Kiya, a secondary wife to the pharaoh Akhenaten, discovered within the workshop of the royal sculptor Thutmose at Amarna, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum collection in Berlin

Portrait study thought to represent Kiya, a secondary wife to the pharaoh Akhenaten, discovered within the workshop of the royal sculptor Thutmose at Amarna, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum collection in Berlin Portrait study thought to represent Amenhotep III, the father of pharaoh Akhenaten, discovered within the workshop of the royal sculptor Thutmose at Amarna, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum collection in Berlin

Portrait study thought to represent Amenhotep III, the father of pharaoh Akhenaten, discovered within the workshop of the royal sculptor Thutmose at Amarna, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum collection in Berlin Plaster portrait study thought to represent the later successor pharaoh Ay, part of the Ägyptisches Museum collection in Berlin

Plaster portrait study thought to represent the later successor pharaoh Ay, part of the Ägyptisches Museum collection in Berlin Statuette of Queen Nefertiti rendered in limestone from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose, on display at the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin

Statuette of Queen Nefertiti rendered in limestone from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose, on display at the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin Plaster portrait study thought to represent Queen Nefertiti, primary wife of the pharaoh Akhenaten, discovered within the workshop of the royal sculptor Thutmose at Amarna, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum collection in Berlin

Plaster portrait study thought to represent Queen Nefertiti, primary wife of the pharaoh Akhenaten, discovered within the workshop of the royal sculptor Thutmose at Amarna, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum collection in Berlin Granite statue of the head of Queen Nefertiti, from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose, on display at the Ägyptisches Museum

Granite statue of the head of Queen Nefertiti, from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose, on display at the Ägyptisches Museum

Footnotes

- ↑ Located at 27°38′11″N 30°53′47″E / 27.63639°N 30.89639°E

- ↑ Krause 2008, p. 47.

- ↑ Reeves. (2005) p. 157.

- 1 2 Krause 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Sweeney. (2004) p. 67.

- 1 2 Sweeney. (2004) p. 79.

- ↑ Tyldesley (2006). p. 126-127.

- ↑ Alain Zivie: La tombe de Thoutmes, directeur des peintres dans la Place de Maât, 2013

- ↑ Zivie, Alain, Pharaoh's Man, Abdiel, the vizier with a Semitic name, Biblical Archaeology Review, July-August 2018, page 23,ff

Bibliography

- Dodson, Aidan (2009). Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-304-3.

- Krauss, Rolf (2008). "Why Nefertiti Went to Berlin". KMT. 19 (3): 44–53.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2006). Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05145-3.

- Sweeney, Deborah (2004). "Forever Young? The Representation of Older and Ageing Women in Ancient Egyptian Art". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 41: 67–84. doi:10.2307/20297188.

- Cyril Aldred, Akhenaten: King of Egypt (Thames and Hudson, 1988), pp. 59.

- Rita E. Freed, Yvonne J. Markowitz, Sue H. D'Auria, Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten - Nefertiti - Tutankhamen (Museum of Fine Arts, 1999), pp. 123–126.

External links

- Sculptor Thutmose’s Complex – image comparisons, Rifkind's World