National Federation of Women Workers

| |

| Founded | 1906 |

|---|---|

| Date dissolved | 1921 |

| GMB (trade union) | |

| Members | 40,000 (1914) |

| Key people | Mary Macarthur |

| Country | United Kingdom |

The National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW) was a trade union in the United Kingdom active between 1906 and 1921 when it merged with the GMB.[1] It was established by Scottish suffragist Mary Macarthur, on the basis of being a general trade union "open to all women in unorganised trades or who were not admitted to their appropriate trade union."[2] Some of the initial aims of the union were to campaign against sweated industries[3] and for a legal minimum wage for women.[4]

Establishment

The NFWW was established out of frustration that existing trade unions were not open to female members. When it was first established the NFWW was met with resistance from others within the trade union movement. The male-dominated unions regularly opposed the idea of "organised women" who would damage the status of trade unionism by the nature of having women who could not vote be part of the political movement.[5]

The earlier established Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) although it promoted union membership to women, it was not itself a trade union and acted instead as an umbrella group for women who were members of other existing unions. The unsuccessful dispute in 1906 of women workers in the Dundee Jute industry highlighted the need for a coordinated union. The Dundee dispute failed due to the inability of the WTUL to raise £100 required for a strike fund to support the strikers.[6]

Those involved in the federation supported opening existing unions, however, at the time the Trades Union Congress did not allow mixed-sex unions affiliation and therefore an all-female union was needed.[2] The NFWW is recognised as having a major influence in influencing the Liberal Party to introduce the Trade Boards Act 1909 which set minimum wages for industries that had a high proportion of female workers.[4]

The NFWW had seventeen branches at the end of its first year and around 2,000 members,[5] this grew to an estimated peak of around 40,000 in 1914.[2][7]

Notable Actions

Pre-War

1910 Cradley Heath Chain Makers Strike

In 1910 the NFWW organised a strike of around 800 women working as Chain Makers in Cradley Heath after they were denied the minimum 11s (55p) weekly wage as set in the Trade Boards Act.[3] Chainmaking was the first industry to have minimum wages set under the act, however for six months workers were allowed to contract out of the new rates, allowing unscrupulous employers to demand or trick workers into agreeing to low rates of pay. This led to concern from the NFWW that employers were planning on stockpiling large quantities of chain made within the six-month window and later dismiss the workers once the minimum wage level was set. Mary Macarthur was also concerned that the result of this action would lead to the impression that having set minimum wages would lead to unemployment increases.[6]

The NFWW worked with employers who were willing from the start to pay the minimum wage by ensuring them that their undercutting competitors would not get an advantage. The only way this could be achieved was to ensure workers for the company's refusing to pay the minimum wage went on strike in August 1910.[6]

A strike fund raised by the union raised around £4,000 (approx. £450,000 in 2018 value) to support the strikers.[3] Part of the success of the chainmakers' strike fundraising was due to the ability of the NFWW and Mary Macarthur to attract wide support amongst newspapers, including surprisingly at the time in The Times, which had historically opposed strike action. Collections were made in local communities across the United Kingdom and Ireland from outside churches, football grounds, factories and Labour Party meetings. A Pathé news film of the chainmakers strike was produced and shown in picture theatres across the country.[6]

Within a month 60% of the employers had agreed to pay the minimum wage requirement and after 10 weeks the final employer agreed on the 22nd October 1910.[8] After the strike found success to raise wages, the remainder of the fund built the Cradley Heath Workers' Institute. The Institute was later to become part of the Black Country Living Museum in 2008, where an annual Women Chainmakers' Festival is held.[3]

Action During the First World War

During the First World War many women were drafted in to fill posts left vacant by men enlisted to armed forces. Between 1914 and 1918 an additional one million women would take up employment. Many of them however found poor conditions, low pay and long hours resulting in a number of industrial actions and disputes with employers supported by trade unions including the NFWW.[9] During the war period trade union membership amongst women increased by 160%.[10]

1915 Cleator Moor Textile Workers

Ainsworth Mill in Cleator Moor created khaki thread for the uniforms of soldiers of the First World War. The workers were paid substantially low wages of between seven and nine shillings for a working week of 60 hours. The local Labour Party MP William Anderson, husband of NFWW leader Mary Mcarthur, called for an investigation into the low rates of pay in the House of Commons. A strike of 250 women and 20 boys followed the demands of an investigation which resulted in a 10% War bonus being paid to employees, alongside official recognition for the NFWW, after six weeks of dispute.[9]

A later strike of 1920, again over low wages was organised at Ainsworth Mill.[9]

1915 Hayes Munitions factories

The NFWW branch associated with the Hayes munitions factories had a membership of over half the women employed by the firm in 1915. A delegation from the union demanded equal pay for the women employed by the firm to end the inequality of wages between female and male workers. Men were paid seven pence an hour while female workers only received three and a half pence.[11]

1916 Newcastle Munitions dispute

In 1916 the NFWW assisted local worker to stage a sit-in protest at a munitions factory in Newcastle over the failure of a local company to pay out on a tribunal award to increase wages for local women workers. During the sit-in the workers knitted socks for soldiers on the front line of the First World War and refused to operate the factory machinery.[11] This resulted in a furious phone call by the then Minister for Munitions Winston Churchill to Mary Macarthur demanding to know why she allowed the workers to stop. Macarthur told Churchill that the women would not go back to work until the tribunal findings had been paid.[12] After 24 hours, the firm relented and back paid the missing wages.[11]

1916 Greenwood and Batley's cartridge factory

Over 2,500 young women went on strike in April 1916 at Greenwood and Batley's leeds factory supported by the NFWW. Their dispute was around the gross differences in pay between the highest and lowest paid members of staff. The firm claimed the action was "unorganised and irresponsible".[13]

1917 Summerson and Sons, Darlington

In 1917 a total of 21 female workers were dismissed from Darlington railway point manufacturer Thomas Summerson and Sons after two of the workers attended an arbitration tribunal between the company and female workers. The NFWW brought a victimisation case against the firm offered to substitute those dismissed with new women but the NFWW demanded that all 21 workers be reinstated.[13]

Post-War

1918 London Transport Strike

The NFWW were involved in the 1918 tram and bus strikes that affected transport in the West London area. By the end of the War the London General Omnibus Company employed 3,500 women with many other firms having large proportions of female workers as well.[14] They demanded "equal pay for equal labour" for female workers.[11]

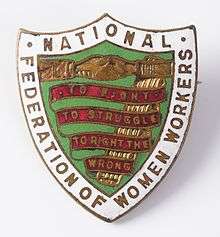

Badge

The NFWW badge is designed in a particular way to mirror that of trade unions of the time in order to elevate the case of women workers to an equal level of that of men. Joint hands are a common symbol in the trade union movement and are a symbol for people working together across boundaries. In the case of the NFWW the two sleeves of the arms are slightly different. One with a sleeve featuring a lace cuff, one not, to indicate a female and male holding hands. The message being of joint action by women and men in the fight for workers rights.[15]

The text "to fight, to struggle, to right the wrong" is a quote from Wages, a poem by Lord Tennyson in part to recognises the support of the then poet laureate for better gender and social equality.[16][15]

The Woman Worker newspaper

.jpg)

The NFWW had a high-profile at the time partially due to their publication of their newspaper The Woman Worker, which collated allegories, anecdotes and related advertisements associate with members of the NFWW. Starting as a monthly publication it's popularity lead to it being published on a weekly basis with a circulation of around 20,000.[4][12]

In the first edition of the paper Mary Macarthur stated in the editorial the purpose of the paper was to "To teach the need for unity, to help improve working conditions, to present a monthly picture of the many activities of women Trade Unionists, to discuss all questions affecting the interests and welfare of women. Such, in brief, is our aim and purpose."[4]

While much of the content was focused on unionism and women's rights the paper also contained lighter content such as features entitled 'The Art of Beauty' and 'Home Hints'.[4]

References

- ↑ "National Federation of Women Workers". TUC History Online. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Cliff, Tony. "Class Struggle and Women's Liberation". Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 England, Historic. "Mary Macarthur and the Sweated Industries | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Woman Worker, September 1907, Volume 1 Number 1". WCML. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- 1 2 "Mary MacArthur: the unstoppable power of organisation | LabourList". LabourList | Labour's biggest independent grassroots e-network. 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- 1 2 3 4 "Mary Reid Macarthur 1880–1921" (PDF). Black Country Living Museum. 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ "Mary McArthur – Striking Shero!". 2015-02-05. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ↑ ""Rouse, Ye Women": The Cradley Heath Chain Makers' Strike, 1910". warwick.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- 1 2 3 Kinghorn, Kristie (2014-11-14). "The battle of the WW1 textile workers". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ↑ Hunt, Cathy (May 2012). "Sex versus class in two British trade unions in the early twentieth century" (PDF). Journal of Women's History. 24 (1): 86–110.

- 1 2 3 4 "Mary Macarthur National Federation of Women Workers". ourhistory-hayes.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- 1 2 "Mary Macarthur". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- 1 2 Archives, The National (2015-10-08). "Striking women: labour unrest among First World War female workers | The National Archives blog". The National Archives blog. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ↑ "The London transport women workers' strike, 1918 – Ken Weller". libcom.org. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- 1 2 "Object of the Month – August 2014 – People's History Museum : Manchester Museums". www.phm.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ↑ "Wages by Lord Alfred Tennyson". www.online-literature.com. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

External links

- British Pathé film from 1911 "Factory Girls Strike" featuring strikers in Camden carrying an NFWW banner.

- Original documents from the 1910 Cradley Heath Chain Makers Strike, University of Warwick

- Oral History recording of Frank Bradbury, munitions worker at Greenwood and Batley Munitions Factory. Includes detail of female workers strike, Imperial War Museum.