Special Organization (Ottoman Empire)

The Special Organization (Ottoman Turkish: تشکیلات مخصوصه, Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa) was an Ottoman imperial government special forces unit under the War Department and was allegedly used to suppress Arab separatism and Western imperialism in the Ottoman Empire.[1] Many members of this organization also played leading roles in the first world war. The main aim of the Special Organization was to re-open the Ottoman parliament. The members of the organization also participated in the resistance against Italians in Libya.[2] It was the progenitor of the National Security Service (Turkish: Milli Emniyet Hizmeti) of the Republic of Turkey, which was itself the predecessor of the modern National Intelligence Organization (Turkish: Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı, MİT).

Activities (1913–1918)

The exact date of establishment is unclear or disputed. According to some researchers, the organization might have been established by Enver Pasha, who placed Süleyman Askeri in charge of the organization on 17 November 1913.[3][4] Its establishment date is rather vague since it was really a continuation of various smaller groups established by Enver Pasa and friends in the aftermath of 1908 Young Turk Revolution[5].

Enver Pasha assumed the primary role in the direction of the Special Organization and its center of administration moved to Erzurum.[6] Many members of this organization who had played particular roles in the first world war also participated in the Turkish national movement.[7] The Special Organization assisted by government and army officials, deported all Greek men of military age to labor brigades beginning in summer 1914 and lasting through 1916.[8]

The first leader was Süleyman Askeri Bey. After his death, he was replaced by Ali Bey Başhampa on 14 April 1915, who held the post until the Armistice of Mudros.[4] During World War I Eşref Sencer Kuşçubası was allegedly the director of operations in Arabia, the Sinai, and North Africa[9]. He was captured at Yemen in early 1917 by the British military and was a POW in Malta until 1920 and subsequently released in exchange for British POW.[4] Ahmet Efe says military archives have detailed information about the organization's personnel. He says Kuşçubası is not mentioned.[4]

The last director, Hüsamettin Ertürk, later worked as an agent in Istanbul of the Ankara government following the Armistice.[10] He also wrote a memoir called İki Devrin Perde Arkası (Behind the Scenes of Two Eras).[11]

This list includes allegedly notable members, according to an interview with its purported former leader Eşref Kuşçubaşı by U.S. INR officer Philip H. Stoddard:[3][12] Although the bulk of its 30,000 members were drawn from trained specialists such as doctors, engineers, and journalists, the organization also employed criminals denoted başıbozuk, who had been released from prison in 1913 by amnesty.[3][13]

Dismemberment

The organization was dismantled following a parliamentary debate and replaced by the Worldwide Islamic Revolt (Turkish: Umûm Âlem-i İslâm İhtilâl Teşkilâtı) after World War I. This organization held its first meeting in Berlin. However, it was forced underground by the British, who refused to let these German allies operate.[13]

In 1921, Atatürk founded another secret organization called the National Defense Society (Turkish: Müdafaa-i Milliye Cemiyeti), headed by the former chief of the Special Organization, Hüsamettin Ertürk.[13]

Kuşçubaşı controversy

Stoddard's book has been criticized by historian Ahmet Efe. He has recently released a book of his own, based on archival research. Efe says that, for example, Kuşçubaşı's own history is inaccurate; he is said to be a graduate of Kuleli Military High School, and Harbiye. The former claim is not established, and the latter is refuted, therefore Kuşçubaşı is not a soldier of any rank. The archives of the Ministry of Defense and the Army Command have no record of Kuşçubaşı.[4]

Efe says that Chief of Staff intelligence reports write that Kuşçubaşı was a mole for the Greeks and the British. He was the 60th person among the 150 personae non gratae of Turkey.[14] Kuşçubaşı is instead said to be the leader of the Anatolia Ottoman Revolution Committee (Turkish: Anadolu Osmanlı İhtilâl Komitesi) which, with the help of British and Greek intelligence, repeatedly attempted to assassinate Atatürk. Kuşçubaşı's brother, Hacı Sami, also took part in a 1927 attempt.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ "MIT, 'Turkey's CIA,' celebrates 80th anniversary". Turkish Daily News. 2007-01-07. Archived from the original on 2013-01-13. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

...the new intelligence agency of the republic was in fact the continuation of the Ottoman Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization)

- ↑ "Elli devletin temelinde TEŞKİLAT'IN HARCI VAR". Yeni Şafak. 2005-11-14. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

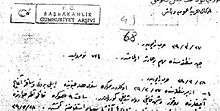

- 1 2 3 Eren, M. Ali (1995-11-11). "Cumhuriyeti Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa kurdu". Aksiyon (in Turkish). Feza Gazetecilik A.Ş. 49. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kılıç, Ecevit (2007-12-17). "Türk istihbaratının kurucusu bir vatan haini miydi?". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ↑ "Teskilat-i Mahsusa" Philip H. Stoddard (translated by Tansel Demirel), 1993, Arma Yayinlari, Istanbul, pp. 49-54.

- ↑ Enver Paşa, Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa'nın yönetilip yönlendirilmesinde birinci derecede rol üstlenmişti., Recep Maraşlı, Ermeni Ulusal Demokratik Hareketi ve 1915 Soykırımı, Pêrî Yayınları, 2008, ISBN 978-975-9010-68-3, p. 252. (in Turkish)

- ↑ Taner Akçam, Türk Ulusal Kimliği, İletişim Yayınları, 1992, ISBN 9789754702897 p. 155.

- ↑ Isabel V. Hull, Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany, Cornell University Press, 2006, IBN 9780801472930, p. 273.

- ↑ "Teskilat-i Mahsusa" Philip H. Stoddard (translated by Tansel Demirel), 1993, Arma Yayinlari, Istanbul.

- ↑ Berkes, Niyazi (1959-12-31). "2 Devrin Perde Arkası". Oriens (in Turkish). BRILL. 12 (1/2): 202–202. doi:10.2307/1580200.

- ↑ Özbek, Öner (2008-09-13). "Yakup Cemil: Devlet içinde devlet olan adam". Taraf (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ↑ Parker, Richard Bordeaux (2001). The October War: A Retrospective. University Press of Florida. p. 126. ISBN 0-8130-1853-6. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

I'm Phil Stoddard, who, at the time, was the deputy director of INR's Near East-South Asia Office.

- 1 2 3 Bovenkerk, Frank; Yeşilgöz, Yücel (2004). "The Turkish Mafia and the State" (PDF). In Cyrille Fijnaut, Letizia Paoli. Organized Crime in Europe: Concepts, Patterns and Control Policies in the European Union and Beyond. Springer. pp. 594–5. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-2765-9. ISBN 1-4020-2615-3.

- ↑ Kılıç, Ecevit (2007-12-17). "Onun da yolu Susurluk'tan geçmiş". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ↑ Kılıç, Ecevit (2007-12-16). "Suikast örgütünün kurucusu". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-12-27.

Bibliography

- Efe, Ahmet (2007). Efsaneden Gerçeğe Kuşçubaşı Eşref. Bengi Yayınevi. ISBN 9789750111433.

- Safi, Polat (2006). The Ottoman Special Organization – Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa: A Historical Assessment with Particular Reference to Its Operations against British Occupied Egypt (1914-1916). Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University. (unpublished MA thesis)

- Safi, Polat (January 2012). "History in the Trench: The Ottoman Special Organization – Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa Literature". Middle Eastern Studies. 48 (1): 89–106. doi:10.1080/00263206.2011.553898.

- Stoddard, Philip Hendrick (1963). The Ottoman Government and the Arabs, 1911 to 1918: A Study of the Teskilat-i Mahsusa. Princeton University. (unpublished PhD dissertation; available in Turkish)