Symptom

A symptom (from Greek σύμπτωμα, "accident, misfortune, that which befalls",[1] from συμπίπτω, "I befall", from συν- "together, with" and πίπτω, "I fall") is a departure from normal function or feeling which is noticed by a patient, reflecting the presence of an unusual state, or of a disease. A symptom is subjective,[2] observed by the patient,[3] and cannot be measured directly,[4] whereas a sign is objectively observable by others. For example, paresthesia is a symptom (only the person experiencing it can directly observe their own tingling feeling), whereas erythema is a sign (anyone can confirm that the skin is redder than usual). Symptoms and signs are often nonspecific, but often combinations of them are at least suggestive of certain diagnoses, helping to narrow down what may be wrong. In other cases they are specific even to the point of being pathognomonic.

The term is sometimes also applied to physiological states outside the context of disease, as for example when referring to "symptoms of pregnancy". Many people use the term sign and symptom interchangeably.[5]

Types

Symptoms may be briefly acute or a more prolonged but acute or chronic, relapsing or remitting. Asymptomatic conditions also exist (e.g. subclinical infections and silent diseases like sometimes, high blood pressure).

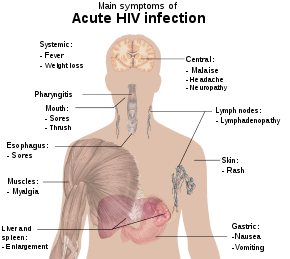

Constitutional or general symptoms are those related to the systemic effects of a disease (e.g., fever, malaise, anorexia, and weight loss). They affect the entire body rather than a specific organ or location.

The terms "chief complaint", "presenting symptom", "iatrotropic symptom", or "presenting complaint" are used to describe the initial concern which brings a patient to a doctor. The symptom that ultimately leads to a diagnosis is called a "cardinal symptom".

Non-specific symptoms

Non-specific symptoms are self-reported symptoms that do not indicate a specific disease process or involve an isolated body system. For example, fatigue is a feature of many acute and chronic medical conditions, which may or may not be mental, and may be either a primary or secondary symptom. Fatigue is also a normal, healthy condition when experienced after exertion or at the end of a day.

Positive and negative

In describing mental disorders,[6][7] especially schizophrenia, symptoms can be divided into positive and negative symptoms.[8]

- Positive symptoms are symptoms present in the disorder but not normally experienced by most individuals. It reflects an excess or distortion of normal functions (i.e., experiences and behaviors that have been added to a person’s normal way of functioning).[9] Examples are hallucinations, delusions, and bizarre behavior.[6]

- Negative symptoms are functions that are normally found in healthy persons, but that are diminished or not present in affected persons. Thus, it is something that has disappeared from a person’s normal way of functioning.[9] Examples are social withdrawal, apathy, inability to experience pleasure and defects in attention control.[7]

Possible causes

Some symptoms occur in a wide range of disease processes, whereas other symptoms are fairly specific for a narrow range of illnesses. For example, a sudden loss of sight in one eye has a significantly smaller number of possible causes than nausea does.

Some symptoms can be misleading to the patient or the medical practitioner caring for them. For example, inflammation of the gallbladder often gives rise to pain in the right shoulder, which may understandably lead the patient to attribute the pain to a non-abdominal cause such as muscle strain.

Symptom versus sign

A sign has the potential to be objectively observed by someone other than the patient, whereas a symptom does not. There is a correlation between this difference and the difference between the medical history and the physical examination. Symptoms belong only to the history, whereas signs can often belong to both. Clinical signs such as rash and muscle tremors are objectively observable both by the patient and by anyone else. Some signs belong only to the physical examination, because it takes medical expertise to uncover them. (For example, laboratory signs such as hypocalcaemia or neutropenia require blood tests to find.) A sign observed by the patient last week but now gone (such as a resolved rash) was a sign, but it belongs to the medical history, not the physical examination, because the physician cannot independently verify it today.

Symptomatology

Symptomatology (also called semeiology) is a branch of medicine dealing with symptoms.[10] Also this study deals with the signs and indications of a disease.[11]

See also

- Category: Symptoms

- List of medical symptoms

- Pathogenesis

- Sinthome

- Symptomatic treatment

- Medical sign

References

- ↑ "Sumptoma, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', at Pursues". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Pathology – Glossary Archived January 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ eMedicine/Stedman Medical Dictionary Lookup!

- ↑ Devroede G (1992). "Constipation—a sign of a disease to be treated surgically, or a symptom to be deciphered as nonverbal communication?". J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 15 (3): 189–91. doi:10.1097/00004836-199210000-00003. PMID 1479160.

- ↑ "What Are Signs And Symptoms And Why Do They Matter?". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Encyclopedia of Mental Disorders: positive symptom". Minddisorders.com. Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-08-20. Retrieved 2010-07-14. Encyclopedia of Mental Disorders: negative symptom

- ↑ "Mental Health: a Report from the Surgeon General". Surgeongeneral.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-01-11. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- 1 2 Understanding Psychosis Archived 2012-12-25 at the Wayback Machine., Mental Health Illness of Australia.

- ↑ The British Medical Association (BMA) (2002). Illustrated Medical Dictionary. A Dorling Kindersley Book. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-75-133383-1.

- ↑ David A. Bedworth, Albert E. Bedworth (2010). The Dictionary of Health Education. Oxford University Press. p. 484. ISBN 978-0-19-534259-8. Archived from the original on 2018-05-09.