Sturm Cigarette Company

The Sturm Cigarette Company (Sturm Zigaretten, in English, Storm Cigarettes or Military Assault/Attack Cigarettes) was a cigarette company created by the Nazi Party's Sturmabteilung (SA).[1] The sale of these cigarettes provided the SA with operating funds.[2][3]

Coercion and violence were used to increase the sales of these cigarettes.[3][4]

Founding

During the 1920s, many cigarette firms in Germany closed, and the market was increasingly dominated by a few large, highly automated manufacturers. By 1933, the Nazi party was attacking the tobacco industry for having foreign and Jewish connections.[2]

In 1929, Arthur Dressler cut a deal with the SA; together, they would found a cigarette manufacturer, and SA members would smoke its cigarettes, with the SA getting a royalty,[5] 15 to 20 pfennig for every thousand cigarettes sold[7] (0.45–0.6% of sales price, given most cigarettes sold at 3⅓ pfennig).[3][8] At the time, the SA charged no membership fees, and was thus financially dependent on donations from the Nazi party leadership. An independent income source was very welcome.[2]

Approached through Saxon Nazi party leader Manfred von Killinger, SA-Stabschef Otto Wagener was interested, and willing to put money towards an SA cigarette factory. The Nazi party offered 30 000 reichsmarks in start-up money; as this was nowhere near enough, Nazi party supporter Jacques Bettenhausen invested another 500,000 reichsmarks.[9] The Zigarettenfirma Sturm was founded, registered as the Cigarettenfabrik Dressler.[6]

Marketing

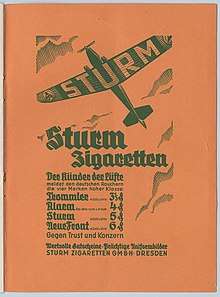

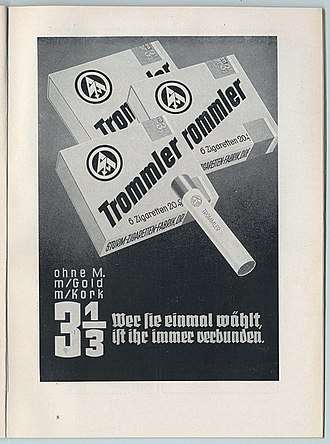

The factory mainly produced four brands: Trommler (Drummer), Alarm, Sturm and Neue Front (New Front).[4] "Neue Front" was the most expensive brand, at six pfennig; "Sturm" was slightly cheaper, at five, and "Alarm" cost four. "Trommler" was the cheapest, at 3⅓ pfennig[8] and given the economic crisis, by far the most popular. In 1932, 80% of cigarettes sold were "Trommler", and in 1933, 95%.[3]

In the earlier ads, all four main brands were listed, and Nazi party imagery and the political slogan "Gegen Trust und Konzern" ("Against the [corporate] trust and the combine") were used. Later ads focussed on the Trommler brand (see images). Apart from print advertising, the company owned a sound truck and hired advertising planes.[3]

The brand was also used to make the prospect of serving in the German army more appealing, with sets of cigarette cards being produced which depicted German army uniforms from history.[10][11][8]

Adolf Hitler's opposition to smoking had limited effects on consumption and sales. While he ordered many localized smoking bans, they were widely ignored. The finance ministry appreciated the taxes tobacco brought in[12] (by 1941, ~a twelfth of state revenues[13]). Aside from taxes, advertising revenues, and Sturm royalties and dividends, Nazi organizations accepted millions of reichsmarks in donations and bribes from the cigarette industry.[2][14][13] The propaganda minister's view was decisive; Joseph Goebbels felt that cigarettes were essential to the war effort.[12] Cigarettes were distributed free to soldiers, including minors, as part of their pay.[13]

Between 1930 and 1940, the per-capita cigarette consumption of Germany rose from 500 to 1000 cigarettes a year;[14] tens of billions of cigarettes were sold annually.[15]

Coercion

There is evidence that coercion was used to promote the sale of these cigarettes.[4] SA members were expected to smoke Sturm Cigarette Company cigarettes exclusively.[1] Indeed, SA members were compelled to smoke Sturm cigarettes;[2] there were bag searches, and fines if any other brand were found.[3] The SA agitated against and punished the use of other brands, especially the market leader, Reemtsma.[2][6] SA men attacked shops that sold rival brands,[2][6] smashing windows and physically attacking the shopworkers.[3]

Profits

Through this scheme, a typical SA unit earned hundreds of reichsmarks each month.[4] A hundred marks would be the SA earnings from the sale of 500 000 cigarettes, at 20 pfennig per thousand.[16] A typical German smoker smoked around 15 cigarettes a day[12] (similar to modern rates[17]), so this would be income from just over a thousand smokers.

At the time, an average-intensity Trommler smoker[12] paid the average wage[18] would spend around a tenth of his gross income on cigarettes.[19] However, the Great Depression hit in 1929, and unemployment rates peaked above 30%, so many were not earning a wage (see graph). The SA recruited particularly among the unemployed and underemployed.[20]

The firm first paid dividends to the SA in 1930. By 1932, it had a turnover of 36 million reichsmarks, and the SA made considerable profits; 1933 saw even higher returns. Money also went to buy new buildings, factories, and advertising.[3]

Replacement

In June 1932, Philipp Fürchtegott Reemtsma, head of the Reemtsma cigarette company, met with Adolf Hitler, Rudolf Hess, and Max Amann[2] (Hitler's secretary, and head of the Nazi party's printing house, Eher Verlag[21]). Reemtsma's ads had been banned from Nazi party publications, but the publications lost money, and the party needed money for election campaigning. Hitler scolded Reemtsma for having Jewish partners, but they agreed to an initial deal on half a million marks of advertising.[2]

Shortly after the Nazis took power in 1933, Philipp Reemtsma asked Hermann Göring, then the highest official in Prussia, to do something about SA attacks against the company and a legal case against it (for corruption). In early 1934, Göring called off the court case in exchange for three million marks; Reemtsma subsequently paid him a million a year, in addition to substantial donations to the party. By July 1934 the Night of the Long Knives had removed the threat of the SA; the SA leaders who had profited from the firm's royalties, and often owned shares in it, were dead or imprisoned.[2]

Reemtsma's Jewish partners had now emigrated, along with many Jewish employees, with help from Reemtsma.[2] After Reemtsma made inquiries, the new SA leader, SA-Stabschef Viktor Lutze, cancelled their contract with Sturm Cigarettes and made a deal with Reemtsma; in exchange for a fixed sum (in 1934, 250 000 reichsmarks), paid annually, Reemtsma would now produce the SA's cigarettes. Sturm, left with unsellable cigarettes,[2] filed for bankruptcy in 1935.[3]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sturm Cigarette Company. |

- Reemtsma (Sturm's successor as the SA cigarette company)

- Health effects of tobacco

- Nicotine marketing, History of nicotine marketing

- Anti-tobacco movement in Nazi Germany

- Anti-Semit (Nazi Party tobacco brand)

References

- 1 2 Proctor, Robert (1999). The Nazi war on cancer. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. pp. 234–237. ISBN 978-0-691-00196-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Erik Lindner. "Zwölf Millionen für Göring". Cicero Online. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Daniel Siemens (2013-09-11). "Nazi storm-troopers' cigarettes" (University department). UCL SSEES Research Blog. Retrieved 2018-08-25.

- 1 2 3 4 Grant, Thomas D. (2004). Stormtroopers and crisis in the Nazi movement: activism, ideology and dissolution. London ; New York: Routledge. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-415-19602-4.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2000). Hitler, 1889–1936: hubris (1st Norton paperback ed.). New York: Penguin. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-393-32035-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas Grosche, Arthur Dressler: die Firma Sturm - Zigaretten für die SA. Chapter in Braune Karrieren: Dresdner Täter und Akteure im Nationalsozialismus. Christine Pieper, Mike Schmeitzner, Gerhard Naser (eds.). Dresden: Sandstein Verlag. 2012. ISBN 978-3-942422-85-7.

- ↑ "Buchkritik: Der Sammelband "Braune Karrieren: Dresdner Täter und Akteure im Nationalsozialismus"". Retrieved 2018-08-20. , citing [6]

- 1 2 3 "Reklame für Zigarettensorte STURM ZIGARETTEN mit Porträts von Yorck und Blücher. Umschlag Rückseite innen von Programmheft Sächsische Staatstheater, Schauspielhaus Dresden. 03.06.1933. Druck; 22,3 x 16,3 cm. Dresden: SLUB Z.4.8 - Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek". Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ↑ Lindner, Erik (2007). Die Reemtsmas: Geschichte einer deutschen Unternehmerfamilie (1. Aufl ed.). Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe. ISBN 978-3-455-09563-0.

- ↑ Goodman, Joyce; Martin, Jane (2002). Gender, colonialism and education: the politics of experience. London; Portland, OR: Woburn Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-7130-0226-3.

- ↑ "Adolf Hitler exhibition in Germany: Hitler and the Germans at the German Historical Museum in Berlin". 2010-10-14. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- 1 2 3 4 Waibel, Ambros (2015-12-21). "Tabak und Kaffee im Dritten Reich: „Verbote wurden ignoriert"". Die Tageszeitung: taz. ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- 1 2 3 Bachinger, Eleonore; McKee, Martin; Gilmore, Anna (May 2008). "Tobacco policies in Nazi Germany: not as simple as it seems". Public Health. 122 (5): 497–505. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2007.08.005. ISSN 0033-3506. PMC 2441844. PMID 18222506.

- 1 2 "Rauchzeichen: Fotoarchiv Reemtsma in der NS-Zeit" (Museum). Retrieved 2018-08-25.

- ↑ Roth, Karl Heinz; Abraham, Jan-Peter (2011). Reemtsma auf der Krim: Tabakproduktion und Zwangsarbeit unter der deutschen Besatzungsherrschaft 1941-1944. Schriften der Stiftung für sozialgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts (1. Aufl ed.). Hamburg: Edition Nautilus. ISBN 978-3-89401-745-3.

- ↑ calculation from numbers given earlier, and on hundred pfennigs to the mark

- ↑ "Raucherstatistiken". Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ↑ "Anlage 1 SGB 6 - Einzelnorm". www.gesetze-im-internet.de.

- ↑ Calculation from figures given in sources; an annual income of ~1600 marks per year, and smoking costs of 0.035 marks for each cigarette, 15 cigarettes a day, and 365.25 days a year

- ↑ Klußmann, Uwe (2012-11-29). "Conquering the Capital: The Ruthless Rise of the Nazis in Berlin". Spiegel Online.

- ↑ "Max Amann: Werke aus Sammlung von Hitlers Verleger entdeckt". Die Welt. 2014-06-13. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

Further reading

- Bachinger, Eleonore; McKee, Martin; Gilmore, Anna (May 2008). "Tobacco policies in Nazi Germany: not as simple as it seems". Public Health. 122 (5): 497–505. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2007.08.005. ISSN 0033-3506. PMC 2441844. PMID 18222506.

- Petrick-Felber, Nicole (2015). Kriegswichtiger Genuss: Tabak und Kaffee im "Dritten Reich". Beiträge zur Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8353-1666-9. ; interview of the author about the book: Waibel, Ambros (2015-12-21). "Tabak und Kaffee im Dritten Reich: „Verbote wurden ignoriert"". Die Tageszeitung: taz. ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- Siemens, Daniel (2017). Stormtroopers: a new history of Hitler's Brownshirts. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19681-8. ; shorter text by author: "Nazi storm-troopers' cigarettes". 2013-09-11.

- Braune Karrieren: Dresdner Täter und Akteure im Nationalsozialismus. Christine Pieper, Mike Schmeitzner, Gerhard Naser (eds.). Dresden: Sandstein Verlag. 2012. ISBN 978-3-942422-85-7.